by Steve Johnson AI CLPE, CFA, Standards Ambassador – Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC) for Forensic Science

In 1998, as the personal computer and cell phone industry was starting to explode, the Scientific Working Group for Digital Evidence (SWGDE) was formed to meet the emerging need for the development of sound, scientific standards, practices and guidelines in the burgeoning digital evidence realm. The federal government, through the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) created the first Scientific Working Group (SWG) in 1988 for DNA as it became a more practical and reliable tool for criminal investigation. Many other SWGs were created over the next two decades as law enforcement agencies and forensics laboratories became more sophisticated and relied upon to solve crimes. SWGDE is one of the oldest SWGs in existence and remains one of the few (along with the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group and the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods) that continues to exist and meet regularly. Most of the other 22 SWGs lost their federal funding in 2013.

In order to fill the void created by the loss of these valuable teams of forensic experts, the Department of Commerce, through the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) created and funded the Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC) for Forensic Science. In its original inception, OSAC was made up of 23 forensic discipline-specific subcommittees, which did not include digital evidence. The forensic community soon recognized the need to add a Digital Evidence Subcommittee to represent the tens of thousands of forensic science service providers (FSSPs) working in this area.

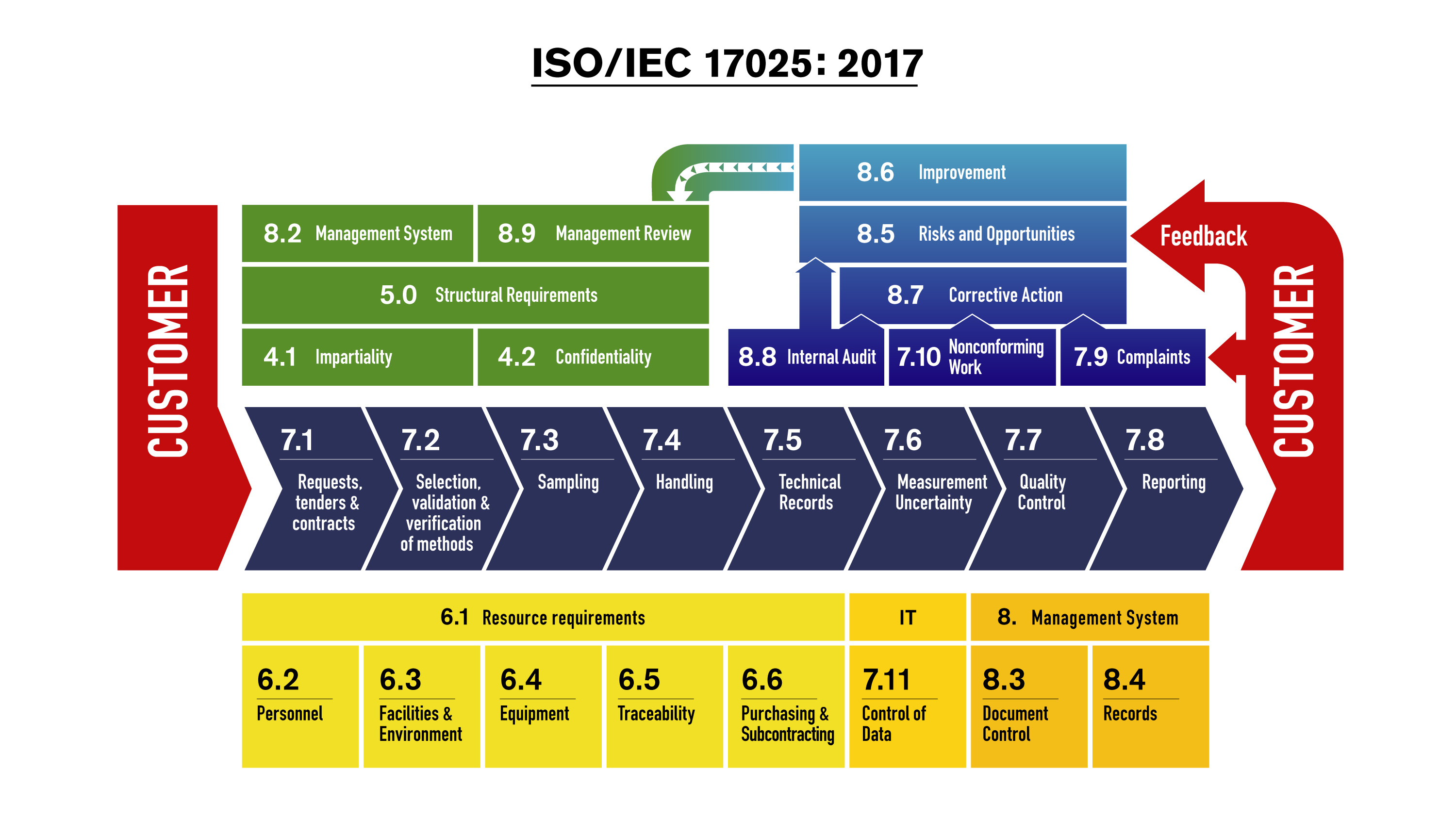

OSAC works to strengthen forensic science through standards. To do this, OSAC:

- Facilitates the development of science-based standards through the formal standards developing organization (SDO) process.

- Evaluates SDO published and OSAC Proposed Standards for placement on the OSAC Registry.

- Endorses and promotes the implementation of standards on the OSAC Registry (for more information on the registry, go to https://www.nist.gov/organization-scientific-area-committees-forensic-science/osac-registry)

In the summer of 2022, SWGDE was officially incorporated as an SDO and is recognized by OSAC in that capacity. This is important to the forensic digital evidence community insomuch as approved digital evidence standards are eligible to be listed on the OSAC Registry. SWGDE has dozens of members representing over 70 law enforcement, academic, commercial, and other stakeholders in the digital evidence community. Given its status as a standards development organization, SWGDE is expected to abide by certain regulations and “best practices” of operation. I am humbled and honored to have been asked to act as a member of an external audit committee that annually reviews SWGDE document development protocols, meeting and attendance requirements and other mandated procedures to ensure the highest level of quality in creating these standards and guidelines. I’m happy to say the SWGDE is meeting every milestone and abiding by their mission.

Standards are only beneficial if they are used, and FSSPs are encouraged to implement the standards on the OSAC Registry. Given the importance of standards implementation, I want to take a moment to share a little more about that effort through this article. Many (if not all) of us are aware of the deficiencies identified in the 2009 National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report “Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward”. One of these deficiencies included a lack of standardization across a number of disciplines. Application of standards that have been developed through a consensus-based process goes a long way toward addressing that gap. OSAC’s mission includes outreach, communication, and support to forensic science service providers (FSSPs) to encourage them to implement standards on the OSAC Registry. Those FSSPs who have embraced implementation are encouraged to complete a declaration form and declare as implementing bodies. By completing a declaration form, agencies, organizations and other FSSPs are awarded a certificate and become integral members of the growing cohort of OSAC implementers.

OSAC’s initial Registry implementation outreach focused on “traditional” FSSPs, the 423 forensic laboratories that the Bureau of Justice Statistics recognized as publicly funded facilities. However, over the last eighteen months, OSAC’s outreach efforts expanded to “non-traditional” FSSPs and engaging these stakeholders in the implementation of standards on the OSAC Registry. The practitioners that work outside of these “publicly funded” labs have been estimated to number in the tens of thousands and come from a variety of backgrounds ranging from small municipal or county laboratories to individual practitioners that contract to law enforcement. In an ideal forensic system, they would all be working in accordance with the same best practices and standards to ensure consistent results are achieved and delivered.

In the fall of 2022, OSAC added a specific position to assist with the implementation outreach effort and expand it to these non-traditional FSSPs such as the digital evidence discipline. I was awarded the opportunity to be part of the team, joining Mark Stolorow (the past OSAC Director) as a “standards ambassador” to engage with forensic science stakeholders. By the time I had begun this journey with OSAC, the organization had identified and acknowledged 100 FSSPs who had implemented (either fully or partially) 129 standards on the OSAC Registry. Up to that point, many FSSPs had been solicited through surveys sent out to the forensic science community over the last two years. Since coming on board in the fall of 2022, another 52 FSSPs have added their names to the list of implementers, and the OSAC Registry has grown to nearly 180 standards. Although there are currently only five digital evidence standards on the Registry, there are over 100 pre-existing or “in development” standards, guidelines, and other documents, many of which will find their way to it. All told, there are standards and guidelines at some level of in the standards development process, including another 60+ published standards that are eligible for the OSAC Registry, 170+ standards that are under development at a standards development organization (SDO), and 165+ standards that are being drafted within OSAC. Suffice to say, a great deal of progress has been made since OSAC’s inception in 2014!

Speaking of 2014, in February of this year, OSAC will celebrate its tenth birthday! I am proud to say that I’ve been involved with the organization since before its establishment, dating back to the first joint meeting of the initial forensic association representatives in the winter of 2014 at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). It was at that meeting that the seeds of this enterprise were initially sown. Since then, I believe the growth of OSAC from its seedling stage to what it has become today, has borne important fruit and continues to bring scientifically sound standards to the forensic science community and its stakeholders. Starting as the IAI’s representative to OSAC’s Forensic Science Standards Board (FSSB) in 2014, getting elected chair of the FSSB in the fall of 2017, becoming (and continuing to serve as) a member of the Facial & Iris Identification Subcommittee, and now serving as a Standards Ambassador for OSAC, I’ve been on the front lines of this enterprise and am excited for the future of the standards implementation effort.

OSAC has initiated a number of outreach efforts to engage with FSSPs and to evaluate the impact of standards implementation. The OSAC Registry Implementation Survey, distributed in the summers of 2021 and 2022, provide summaries for each discipline where standards were available on the OSAC Registry. Since then, OSAC has established an “open enrollment” period during which FSSPs were encouraged to update or initiate their implementation activities using the OSAC Registry – Standards Implementation Declaration Form. To better streamline and simplify the declaration process, we are currently establishing an electronic platform that will give current and potential new implementing FSSPs the opportunity to easily update or complete a declaration form online. Additionally, over the past year, the FSSB formed an Implementer Cohort Task Group made up of a diverse group of professional organizations, authoritative bodies (e.g., accrediting and certification bodies), practitioners, OSAC leadership and OSAC Program Office staff to help support future implementation initiatives.

Looking ahead, OSAC will expand its engagements to include more communications with legal, academic, and corporate stakeholders. In the meantime, as the 2024 fiscal year is well underway, there are more volunteers that have come on board to support the OSAC enterprise. Many members, whose terms recently expired, have brought their volunteer services and passion for forensics to other sections and subcommittees where they will continue to support OSAC as affiliates. In my service as Standards Implementation Ambassador for OSAC, I intend to reach out to as many stakeholders in the digital evidence community as possible since the thousands of FSSPs in this discipline have as much invested in the process as anyone. I encourage digital evidence practitioners and FSSPs to follow the progress of OSAC and consider getting more involved in the organization to help shape the future of forensic science standardization. After all, improving the forensic sciences through the development of sound standards and guidelines is critical to the successful performance of thousands of forensic science service providers, especially those providing forensic support in the fast-growing cyber world.

Steve Johnson is a retired law enforcement supervisor with a background in latent print examination, crime scene investigation, forensic art and facial identification. He is a Senior Advisor for Ideal Innovations and is currently contracted to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science (OSAC). Mr. Johnson is a Past President and Board Chair of the International Association for Identification (IAI) and was the IAI representative to the OSAC Forensic Science Standards Board (FSSB), serving as Chair from 2017 to 2020. The OSAC Mission is devoted to strengthening “the nation’s use of forensic science by facilitating the development and promoting the use of high-quality, technically sound standards”.