Discover how tailored, culturally aware mental health support can help digital forensic investigators cope with the hidden trauma of their work.

The following transcript was generated by AI and may contain inaccuracies.

Paul: Welcome to this special episode of the Forensic Focus podcast. Today I am honored to be joined by someone whose journey and work are having a profound effect on the well-being of those in high-pressure, high-risk roles. Hannah Bailey is a subject matter expert in mental health and well-being, and founder of Blue Light Wellbeing.

She works as a psychotherapist, trauma therapist and well-being coach, supporting individuals and organizations through therapy, coaching, training, and education. But what makes Hannah’s perspective so valuable, especially in digital forensics and frontline responders, is her own lived experience.

Hannah served in frontline policing for 15 years, including roles in emergency response, CID, and major crime. Her career, while fulfilling, was not without significant personal cost. She experienced burnout, PTSD, and overcame a breast cancer diagnosis – challenges that ultimately led her to leave policing and embark on a journey of recovery and reinvention through Blue Light Wellbeing.

Hannah now dedicates her life to helping others in similar roles navigate the mental health challenges they may face. She brings not only clinical expertise, but also cultural credibility. She understands what it’s like to be in these roles, the toll it can take, and what real practical support looks like.

In this episode, we’ll be exploring Hannah’s powerful journey, the founding of Blue Light Wellbeing, and how informed approaches can make a difference for those working in digital forensics and across the broader blue light community. So whether you are on the front lines, behind the screens, or supporting those who are, this is a conversation you will not want to miss. Welcome to the podcast, Hannah.

Hannah: Thank you Paul, and thank you for that lovely introduction. I’m really delighted to be here.

Paul: It is really good of you to join us tonight. So can we begin with your background?

Hannah: Yeah, of course. I know you touched on it in that introduction. So I was a serving police officer in West Midlands Police here in the UK for 15 years. And as you rightly said, Paul, this was a career I loved – really loved.

I joined at 21. I didn’t have a degree in anything else. I hadn’t done any other career, so it was absolutely the career for me. I was very passionate about it. It was my identity. I just loved it.

And I have to say Paul, because of the work and the roles and the jobs we went to, as difficult as some of them were, I would say we laughed every day. I had a great team, great sergeant. We laughed every single day and I’m sure that was part of why it was going so well at the start for me.

But things changed. As much as I absolutely felt I was going to do 30 years service in the police, as we do in the UK, and that was going to be me… As you will know, life throws us curve balls, doesn’t it? Changes that we did not plan along the way. And I certainly didn’t.

It absolutely does, doesn’t it? And so I’ve learned that’s probably the biggest lesson I’ve learned. It did exactly that to me. So I would say probably for about two years before I left, my mental and emotional health went downhill.

It wasn’t one big thing that happened or one awful job, because I know that can be the case for some people. But I think probably the majority of officers or frontline workers who are struggling – it’s probably that repeated exposure, that sort of drip effect that we hear a lot about in frontline roles.

And I’d say that was the same for me. I didn’t think there was anything that had particularly affected me. I felt I dealt with it all really well, but obviously not. We had no training, did we Paul? No education, no awareness of it. There was a huge stigma and taboo, which I was part of by the way. I was part of that culture because I didn’t know any different.

And I would say there were a lot of changes at work as well. It wasn’t just the jobs that we were dealing with – there were a lot of changes within the structure and teams at work. And I had a lot going on at home as well for about those two years. Some issues at home.

So I think it was like a sort of melting pot for me – everything coming at once. I just didn’t have any space to deal with anything, think about anything, have a breathing space. Nothing at all. And I became quite unwell.

So as you touched upon, I had undiagnosed PTSD at the time. I wouldn’t have known what that was. I wouldn’t have even really known that phrase, I don’t think Paul, at the time. And I think I would’ve just carried on. And I did carry on because I had no idea what to say, who to turn to, who to talk to.

So I did try and carry on. And I think I probably would’ve done that until I broke. But another intervention came and I found a lump in my breast. And as you said, I had breast cancer.

So I went through breast cancer the way I think you should – the way I was taught to in the police – which was grit your teeth, put a smile on your face and get on with it. And I did. I was determined I was going to fight it and battle it and get through it and put it behind me. And so I did that.

And I didn’t face anything about how I’d got to that point, Paul, at all, or how sick I really was at the time. So after nine months off work, I went back to policing. Even with everything I had been through, I still wanted to be a police officer.

I didn’t know how else to be or where else to work or where else I might fit if I wasn’t a police officer. I had no idea. So the only option I felt was to go back to policing, determined that I would do something different and it would be different and I might look after myself. But again, I had no idea how to do that or what that entailed or what that meant.

So actually I had cancer twice. My cancer came back within a year. It had mutated, so very rare, very aggressive, with a very poor prognosis of survival.

And I think it was only then – and it probably should have been earlier than that – but only then did I wake up really and think, “I have actually got to face what’s going on here and why I am so sick.” So actually, in the end, I didn’t do chemotherapy or radiotherapy that second time.

My prognosis with those treatments was so poor and I just realized I had to rethink everything. Actually, Paul, reassess everything. I learned how to… I went to Germany for medical treatment in the end. But I researched how to be well long term – mentally, emotionally, physically, spiritually even.

I just thought there’s going to be no stone unturned. I’m going to find out how I get better and how I stay better, which I think is really important – to consistently be well, not just put a bit of a sticking plaster on and hope it will all go away, which is what I’d done so far.

And so yeah, part of that was resigning from the police for me, which even with everything I’d been through was so difficult. I was devastated to leave policing. I can see you nodding your head, so I’m sure you felt the same as well. Even with everything, I was devastated.

But it was the right choice for me, and I became very well. I faced it all – what I needed to through therapy – but physically as well. I changed my lifestyle and how I looked after myself and became very well. I realized that I probably had some skills there from policing that I could actually help others with and turn it around. I decided to retrain professionally, as you said, and come into a different career. So yeah, that’s how I come to be here today.

Paul: I think you’ve touched on so much there. Can I ask, during the period where you did become unwell through suffering from PTSD, et cetera, and then of course that awful news about breast cancer on top of that, what support did you get from the force you were working with?

Hannah: None at all. I’m sorry to say that. And I want to stress here – my sergeant and inspector were nice guys, by the way, so this is not about them being horrible people. They were nice people. And I had good practical support in that I had nine months full pay.

There are lots of jobs that would not do that. And that was an incredible gift financially – to give us that security through that time. I’m not somebody who sits here and police bashes because that’s not what it’s about. And it’s not useful. It isn’t.

But it’s about learning, because nobody had a clue mentally or emotionally, including me, how to support me through any of that at all. So yeah, no emotional and mental support at all. But practically, yes, good. And they were clear that I had the time that I needed to physically get well.

I just had no idea how to mentally and emotionally get well, and nor did they, to be honest, Paul. So yeah, we were all blind leading the blind a little bit through that period of time.

Paul: I asked the question because I quite often hear from DFIs and other people still in policing that the support they are provided is minimal at best, but in quite a few cases there actually isn’t any. And I still find that astounding.

When you consider – and I’ve said this many times now – you send a cop out onto the street, they go out with body armor, tasers, gas, you name it. They’re fully equipped to be protected physically. When it comes to mental health support, there are apps, but there is next to nothing there.

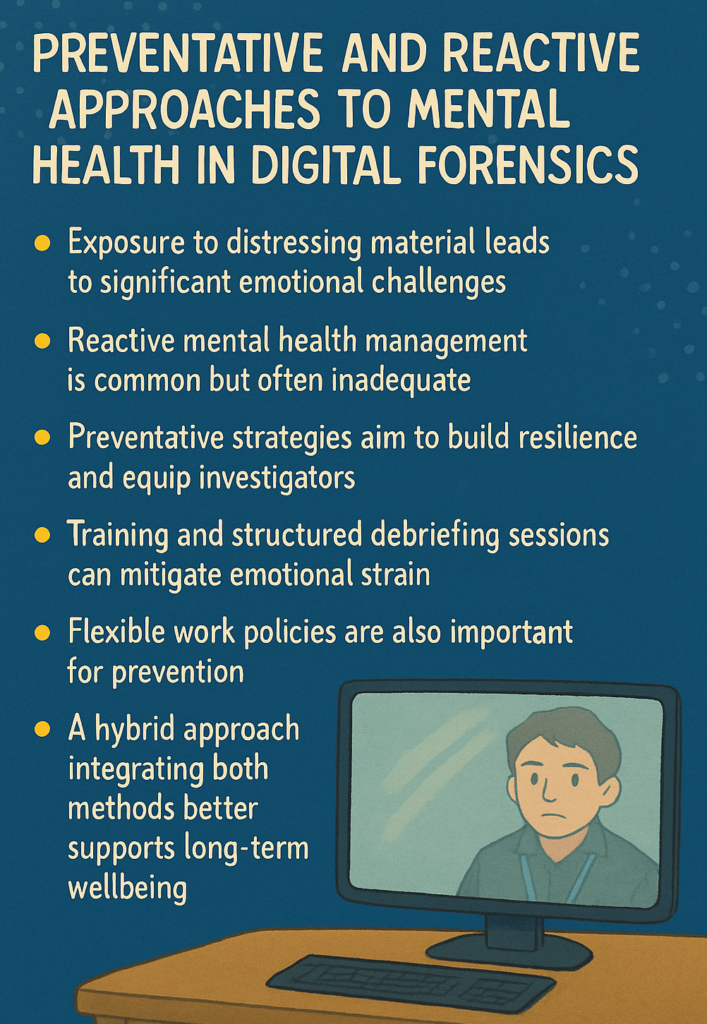

For me, that just doesn’t make sense because once someone becomes susceptible to the stressor, then it takes an awful long time to recover from that. So you’re losing that staff member or those staff members while they’re recovering. Yet that could be averted by putting in a proactive approach to doing this.

For me, it just doesn’t make financial sense not to have it there, not to have it available when it’s needed.

Hannah: Yeah, a hundred percent. And not only available when it’s needed, but – and I think you and I are probably both passionate about this – in a proactive sense as well. Because I just think policing is very reactive, isn’t it?

It’s very reactive and certainly when I was in there, we reacted to hotspots and crime spots and so on and so forth. And it’s got better over the years at looking at that proactively. How do we fight crime or hotspots or that sort of school to prison pipeline? How do we look at that proactively? And I’m like, surely that applies to mental health and wellbeing as well.

If we look at it proactively, how much of a difference we could make – not just to those individuals but the organization as a whole, the community. Every single person and group benefits if we look at it proactively.

Paul: I cannot agree more. Police have developed over the years. They are professionals out there. I’m absolutely not here to police bash if you like, because I’ve got the utmost respect for those men and women who go out on the streets and put their lives on the line on a daily basis.

Hannah: Yeah, absolutely.

Paul: In the same way, DFIs sit in front of screens every day and they are exposed to the depths of humanity. And in both cases, their caseloads are ever expanding. And there are a lot of stats out there to prove this. Yet when it comes to the development of mental health services, they stay stagnant. They haven’t changed for years.

Hannah: It is astounding. And what I would say is the shame as well, Paul, is that it’s not uniform – excuse the pun – but it’s not uniform across the forces. And I don’t know in terms of the digital forensic world, but I’m sure you could tell me if it’s uniform across different companies and organizations.

But I’m lucky enough because I’m freelance – I work with so many different police forces, and you get forces with no mental health and well-being budget. Zero. And you get forces that are really getting there with that proactive aspect coming in. They have good support, good awareness, less stigma.

So it’s really different across different police forces as well, which is such a shame because it is a little bit of a postcode lottery, and that’s a shame.

Paul: You’ve just taken the words out of my mouth. I was just going to say to you, I talk to so many DFIs across the country and some DFIs have got a great service going on. Outside of law enforcement, I know there are some private companies who are really proactive around the mental health of their employees because they want to protect them and realize the value in them.

But then you talk to other DFIs who tell you there is either nothing or the bare minimum, which isn’t even a sticking plaster in some cases. And you are exactly right. I think you used the term postcode lottery. It is exactly that. It depends where you work and what the budget is for that force, whether you get a reasonable amount of support or not.

But that shouldn’t be the case. It should be unified across the country with standards set so that DFIs are fully supported. That’s what I’ve been campaigning for a very long time now.

Hannah: Also because I think certain roles are seen as more high risk. And I do think with digital forensics – because it’s perhaps not the same physical risk for them – I don’t think it’s seen, perhaps sometimes by forces, as the risk that it is. And I would say the role they do with the constant viewing that they are exposed to – certainly in terms of mental health and well-being – they must be one of the most high risk. I would suggest that.

Paul: Absolutely. I can’t think of another job either in or outside of law enforcement which is such a constant trauma-facing role.

Hannah: Yeah, I agree. And also, because when you are looking at stuff on screens or any of the digital formats all the time, you are not getting that same human connection that you might do on a team going out to a job or even just being crewed up in a car with somebody. And then, I don’t know, like all going out to a job as a team to put a door in or something.

So you’ve got more isolation kicking in, I would say, in a digital forensics role than you do in traditional sort of frontline policing. And that would then always increase the risk of the trauma exposure.

Paul: I would absolutely agree. Can we talk about some of the work that you do with DFIs and other forces and such?

Hannah: Yeah, absolutely. Thank you. So I do a mix of things really. In terms of going into different forces or other similar organizations like the NCA – those kinds of law enforcement or investigation roles – I go in and really do different types of training and education, I would say.

Depending on what a team is struggling with at the time. So often around resilience, overwhelm, burnout, PTSD. I go in and talk about my personal experience, because as you just said, that helps a little bit with that credibility, that connection. They know I understand their world.

It really does because they know that what I’m talking about, I really genuinely understand. And I’m genuinely trying to find those ways to help them – not in a bit of a tick box type way. So that would probably be the most common areas that I go in and help those roles with.

But sometimes it’s quite specific, so it might be around FLOs, SIOs. So particular types of roles they’re undertaking. Child sexual exploitation is a really common one because the level of trauma is just so high.

Sometimes the other one as well is change management. So a lot of companies and businesses have change management specialists and that sort of thing. I’m not one of those – I didn’t mean that badly either to change management specialists. Sorry. Nothing wrong with what you do, but I don’t do that.

But I do it in terms of the mental health side of significant change within an organization, because I know how much it affected me, Paul. At a time that I was struggling, we also went through significant change on the teams.

I didn’t know my supervisors, I didn’t know any of my colleagues. And I think that matters so much when you’re in such high risk and demanding frontline roles. You really need to feel comfortable to be able to speak out, and if you don’t know anybody or you don’t trust them…

And also Paul, I thought that they didn’t really know me, so they didn’t know my reputation – that this wasn’t me. It was really unlike me to struggle or not settle or not be able to deal with jobs in the same way. That was so unlike me. So I felt they didn’t know me either. So I didn’t want to speak up and say I was struggling.

Significant change in these types of roles in organizations is a massive impact on mental health and well-being. And so I often go in as well and deliver inputs and training around that. So yeah, that’s what I tend to do for organizations.

And then I work with individuals as well with trauma therapy and well-being coaching. And I think that’s really important to highlight because, again, you and I would be passionate about people… It would be so great if people came a bit earlier. It really would.

So I think it’s one of the myths I like to dispel if I can about therapy. I think people think – certainly in these roles – you go when you’re broken and you are on your knees. And I do get, of course, people who come at that stage, but it’s lovely if I actually get people that are coming earlier – maybe struggling or something not going quite right and they could just do with a bit of help, support, that coaching side.

And it’s really useful. And like you said, much quicker, that proactive side – much quicker to get you back on your feet and get you back into the role or work or life that you love. So yeah, it’s one of the myths I want to help dispel: please come earlier if you can, when you’re struggling and just need a bit of support.

Paul: This is why I’m a big advocate for the proactive approach to mental health, whether it be in digital forensics or uniform frontline cops or indeed, private companies who employ DFIs. Because for me, the proactive approach could take the form of psychoeducation prior – long before anybody succumbs to the stressor, should I say.

If, in my opinion, individuals are taught about what PTSD is, what it looks like, what the signs and symptoms are, how it can affect you physically, how it can affect you mentally, then the earlier they recognize those signs and symptoms and are then able to find the help to reduce them, then the stronger they become, the more resilient, the more productive they continue to be. And I advocate for that time and time again. Mental health support needs to develop.

And I think that echoes beautifully in what you’ve just said.

Hannah: Yeah, and it’s interesting that you said the word psychoeducation, because that is what I start nearly every training input with. Because if we don’t understand how the brain works well and how it processes stress, shock, and trauma – which our brains can do really well and really efficiently, and it’s set up to do that.

But what happens when it goes wrong? What does it look like when it goes wrong or feel like? As you said, what are those signs and symptoms? And then really importantly – we were discussing this, weren’t we, just before we started – the fact that we can put this right. Actually we can recover from this.

And you and I are sitting here as examples of that, having both been through our struggles with PTSD and mental health and are really well. Doing really well, really healthy, really balanced. That function in our brains to process stress and shock and trauma is back fully functioning again, and it’s absolutely repairable and recoverable. It’s such an important part of that education for them.

Paul: It absolutely is. Like you said earlier, taking that decision to resign was one of the hardest things you’ve ever done. I absolutely know where you are coming from. I will openly say, when I walked out of the station on my last day, I was in tears.

Hannah: Yeah.

Paul: But at that point, I had some level of insight into the fact that I was really unwell. And I remember vividly the first time I met the therapist who I worked with. I was absolutely terrified.

Hannah: Yeah.

Paul: Absolutely terrified to open that box and share what was inside. I’m thankful that the therapist that I worked with was absolutely amazing. She just got it.

Hannah: Good.

Paul: But I’m thankful also that she was culturally aware as you are. Because I recently attended a conference and this really shows how important it is to have a background such as yours.

I was recently at a conference where one of the delegates told me that they were a practicing DFI and they shared that they had a psychologist who regularly came in to see them, which they benefited from massively. But during a group session that was being held, one of the DFIs shared a particularly traumatic case, which upset her so much she left and never came back again.

Now I have to say from my point of view, the message that sends to a DFI is “nobody can deal with this.” Whereas, because you’ve lived it, you haven’t just done the job, but you’ve lived the experience of being unwell. You’ve lived through the stresses and you’ve come out the other end a much stronger, more resilient, better person. And I think the cultural awareness attached to therapy is highly underrated right now. I don’t think people realize the value of that.

Hannah: Yeah, no, I completely agree with you. In fact, I think the people going for therapy absolutely value that, like almost more than anything actually. But I don’t think perhaps leaders and organizations do, and they set up, let’s say an EAP, and as long as that’s provided and funded… I think sometimes, if I’m honest, they’re not that bothered how effective it is. It’s just set up and it’s available. That’s being honest.

And you are absolutely right and I hear this actually time and time again, exactly what you’re saying. I had a client who was involved in something incredibly traumatic and before she came to me was detailing that to her counselor. And the counselor got almost a little bit cross and said, “Look, you do know this is distressing for me, don’t you, as well?” when my client was crying. I know. I can see you shaking your head. Exactly. That’s what I was like. I just don’t think you should be a therapist, I’m going to be honest, if you can’t hear other people’s trauma.

But yes, that cultural awareness. And so of course my client felt like she couldn’t talk about that, that she was upsetting the counselor. But also, as you said, you just think “my trauma must be so awful. A counselor can’t hear it and a counselor’s upset by it.”

So you just start to think that you’re in this most awful place that you can’t recount this hideousness that’s in your head and that you can’t get better from it or be relieved from those traumas that it’s causing. And that’s not the case at all.

And yeah, you are right. For me, I don’t want to sound like “aren’t I hard-nosed?” But it doesn’t shock me and there isn’t anything that’s going to shock me I don’t think anymore. I can listen to that as both a therapist and an ex-police officer who has been on both sides of those, and I think that’s really important.

Paul: I think it’s super important.

Hannah: Yeah.

Paul: The sad thing is there aren’t that many culturally aware therapists.

Hannah: And that is the shame, isn’t it? We need people to leave policing and come and be a therapist. And I think that’s growing, Paul, if I’m honest. As we’re talking, I think it’s growing, but you’re right. There’s not enough.

I think you can be… Are there people out there that I’ve met as therapists and they’re not ex-police or whatever, and just seem to have an innate understanding, to be fair to them? Yeah. I don’t know where that comes from, but they do seem to have an innate understanding and a way of taking on that type of job and trauma.

So can it exist without our backgrounds? Yes, it can. But is it much more credible or likely if you’ve had our backgrounds? Yes. Probably.

Paul: Yeah, I agree. So I know you trained in Brain Working Recursive Therapy. Can you tell us about that and how that applies to the therapeutic process?

Hannah: Absolutely. So just to say again from a client perspective, how I found BWRT was looking for a therapy for my PTSD. So I had been in probably more traditional therapy, if you want to call it that, for about 18 months, two years. And it was useful. This is not me saying that’s not useful – it was, and I had got to a much better place and was doing much better.

But I still had what I would phrase as hideous flareups of PTSD. Hideous. And they would just overcome me, probably last for about three days of physical pain, almost paralysis, anger, shame, bitterness – it all came out Paul in those three days. So it was not a pretty sight.

I couldn’t work, that kind of thing. I just survived really for the three days or so, and then felt like I’d been in a punch up and a fight for about a week afterwards. And then would get back to life and my normal life as it was then – in a better place.

So I was searching really for something that I just thought, “I just don’t want this anymore. I don’t want to manage PTSD anymore. I do not want it.” And they are different things. The reason I found BWRT was through searching online.

One of the things I loved about it is that you actually don’t have to recount your trauma in great detail. And I hadn’t really heard of that before and I felt I’d done a lot of that with the two years of therapy I’d had. And you don’t, and that’s quite unusual for therapy.

So you obviously have to know some of the content of what people have been through, but I think if you think of policing, of DFIs, all that, you actually don’t have to recount the trauma in great detail. And it really spoke to me that would be something I’d like to do and it’s quite quick and effective.

And I just thought, “I’m going to go for it.” And it was brilliant and it was all that it just said and promised, and I have never, ever had since then any flare ups of PTSD. I’ve had no nightmares, no flashbacks, nothing like that, no symptoms at all of PTSD. So incredibly life changing for me. And so I decided to train in it as well.

I was already a well-being coach but I thought actually people were coming to me with more trauma because of my contacts and backgrounds. I didn’t really feel equipped to deal with that as just a well-being coach. I thought, “I’m going to train in this.” So I gained my qualifications in it as well.

Level one and level two – they’re not actually better than each other. Level one and level two are just different approaches, different ways of dealing with trauma. And it absolutely transformed how I dealt with trauma clients. It’s just been incredible since that time.

And I also wanted to do more qualifications. I like learning. So you can never stop learning about the brain and the body really, can you Paul? To be honest. So I do, I love learning as well, but I wanted to get those qualifications to be recognized in this field.

And so I did a level seven post-grad in trauma therapy as well. And as fantastic as that was, and as much as it massively added to my skillset, understanding, education – it is still BWRT that I go back to with nearly every client.

Paul: Incredible. It’s interesting that you’ve got such a wide skillset actually, because that must allow you to pull from each therapy if you like, to individualize it for a client.

Hannah: Yeah, absolutely. And I do love that bit of it because people might come with really similar stuff, but everybody’s different aren’t they? And there is not a one size fits all with therapy. So I do love that side and I love that.

Where I’d say my trauma therapy and BWRT comes in is helping almost with all your past stuff, if that would be the right word. We help resolve or move or shift that trauma. But the well-being coaching is like looking ahead and how do you move ahead now? Because therapy can be great, but I would like people to be well long term.

So how do I help them with that? What does that structure look like? The boundaries, what skills or experiences could they try or give a go or be open-minded to? So I love that it’s all encompassing. I hope with those different hats that I wear.

Paul: I’m actually smiling, because what you’ve just described is the therapeutic process that I went through myself.

Hannah: Brilliant.

Paul: So all I expected was for the therapist to deal with the weight I was carrying of the trauma that I had been exposed to. What I didn’t expect during the process is the fact that she was going to make me stronger going forward.

Hannah: Yeah. Brilliant.

Paul: And she absolutely did. The process itself – speaking from experience, for me personally, it was a difficult one to start with, but as the process went on, it became a lot… I don’t want to say easier, but a lot smoother. It became almost natural to open up and discuss really difficult things with her. And just like you, I came out the other end a much better, much stronger, much more resilient person for it.

I’ve been asked, like we discussed earlier, I’ve often been asked, “If you had to go back into therapy, would you do it?” In a heartbeat.

Hannah: Yeah, agreed.

Paul: Knowing what I know now, I would do it in a heartbeat.

Hannah: A hundred percent and I would do it earlier, certainly for me as well. When people say “I should have come to you earlier,” I say, “Look, I had PTSD and two lots of cancer before I woke up and realized I better have therapy.” So I get that. I’m the queen of avoiding therapy, but so I really understand.

But a hundred percent I would do it. I’d do it again and I’d do it earlier. And Paul, I have to have supervision for the work I do. And so it just becomes natural just to take this to them, talk it through, let’s find a solution. Let’s work it through.

If I need a cry, I don’t often now because I’m in a different place, but if I need a cry with some of the stuff I hear all the time, then I have a little cry or get angry or get despairing, and then we work it out and I’m good to go. So I know the benefit of it. So does my brain. It knows that. It knows it will be better once we’ve done that.

Paul: So you’ve just mentioned something really interesting there, and it’s something that I’ve thought if it was applied in digital forensics as a proactive approach, as part of the proactive approach, it would help spot those early warning signs. And that is, you mentioned supervision right now, just like you.

As I work in the NHS now as a psychologist, I get weekly supervision where I go and talk to a colleague of mine who is also a qualified psychologist, and we will talk about the caseload that I’ve got and how I feel about that.

It is an excellent opportunity, not just to offload, but to gain another opinion on difficult cases that you’re working with, which massively helps reduce stress that you’re carrying.

Hannah: Hugely.

Paul: I’ve often thought, and I’ll be interested to hear your views on this, if this was applied in digital forensics, whether it be a weekly or biweekly meeting with say a mental health first aid trained individual, I’ve often thought that would in itself help DFIs offload.

Hannah: I completely agree. And what we’re missing is there are so many benefits, not just the offloading as you said. I mean that in itself… And everybody knows that, don’t we Paul? If you just go and meet a mate at the pub and offload, that feels better, that feels nicer. So we know that helps people to come in, talk and offload.

There are so many other things as well. If you are sitting with somebody trained, they can look for certain signs, certain words, certain… even just facial expressions or how the energy or the mood drops when they talk about certain things or people about their job.

So that trained person could look for things as well. But the other thing we’re missing is, again, which I didn’t have, but I do have with supervision, is building that trust. And if you saw somebody every week or even every month, just even to chat if you want, about holidays…

What happens in the brain is that you start to build trust, connection, rapport, relatability, credibility, all those things so that if there’s a time that DFIs or anybody else needs to then say “this has actually been really shit,” or “I’m struggling with my workload” or whatever that is, it’s 10 times easier to say to somebody that you’ve been meeting every week, every month, and have gotten to know, and got to trust and got to relax around, and all those things that the brain likes. It loves all those things, and we would be providing that for them and it would make it 10 times easier to start having those conversations earlier.

Paul: Yeah, I absolutely agree. It’s all about building that safe, non-judgmental space where someone can genuinely offload and become far more relaxed and de-stressed than when they walked through the door, isn’t it? It’s about building up that trust.

Hannah: Yeah, and I think coming back to that, as you said, that cultural awareness and credibility, I think that trust already is built. When they come to people like you or me, because we’ve had those backgrounds and those roles, there’s already a level of trust there.

They know I’m not going to judge them. For example, if they want to… people talk to me as I’m sure they do to you about these horrific jobs and they often talk quite clinically, quite coldly, quite matter of factly. There’s no particular tears or distress about some of it. And they know I don’t judge that. That’s not because they’re these cold monsters or anything. That’s just how they have to talk about their work.

And that’s completely normal to me actually. And also making jokes about it and stuff – those are all completely normal. So that trust and that non-judgment bit is there already.

Paul: It is. And when you talk about the clients that come to you and the way they talk about the trauma that they’ve been exposed to, I think from my point of view, when I reflect, you talk about it so openly with someone who understands, and to quote you, in quite a cold manner because you become normalized to it.

Hannah: Yeah.

Paul: It’s what happens, it’s what you’re used to. It’s what you see every day.

Hannah: Actually weirdly as well, talking about it normally I think can help the brain process it.

Paul: The way people talk about the trauma, you’re right, it must come across to people who haven’t been exposed to that in quite a cold way, but you become normalized to it. It becomes their normal, doesn’t it?

Hannah: Yeah it really does. And I think actually that’s right. I think there’s a line, isn’t there, Paul? Between having to normalize what they see and deal with – they have to, or their brain won’t process it at all. If everything is this incredibly heightened times a hundred trauma, their brain won’t be able to process that every day.

So if they normalize it, you can process it much better. But I know it also moves into a line of when you’re so desensitized that you lose all emotion or all connection and stuff. And that starts to affect, obviously, as we know, your private life and your relationships.

And I think it’s quite a fine line to be fair for DFIs, for law enforcement – how emotionally involved you remain in your job, but in your life as well. So yeah, I think they have to normalize it to a level that hopefully remains healthy.

Paul: Yeah, we’re drawing to a close now. Hannah, do you have any final words for the DFIs and everyone else watching out there?

Hannah: I think we’ve touched on it a bit, but if you don’t mind me just finishing off, I want to dispel a few myths a little bit really with modern therapy because I think it’s part of the stigma of people not coming forward. So maybe we could dispel some of them.

Just to finish off, my first one I’ve already touched on: please don’t think you have to be broken to come for help. You really don’t. So come as early as you’d like. Even if just for a chat to talk something through, to get different boundaries, different structure, whatever. Come as early as you’d like. Please don’t wait if you just want some help.

The second is that, again, we’ve touched on this – modern therapies have really moved on and absolutely there is a place for talking in depth regularly with a counselor or a therapist, but there are lots of different modern therapies and BWRT is one of them, but there are lots of others.

That genuinely are moving people on differently, more effectively, more quickly. So come and explore the different therapy options. Chat to people, chat to specialists, get word of mouth, anything like that, but explore it before you shut it down and think “I’ll just be stuck in therapy for two years and not move on” or “lying on a couch” or whatever people think therapy has to be.

Paul: Which is not the case, not these days, right?

Hannah: Really not. No, it’s really not. It’s got much more modern. Do your research and find somebody. I think any therapist worth their salt would give you a free consultation. I do. So that you can chat, ask questions: what does it involve? How long, roughly might this take? Costs involved, that sort of thing. So yeah. It’s really different now. Give it a go and give it some research.

And then lastly – and I’m so glad we are both on this page – accepting that you need therapy is not some downward spiral to the end of your career or life. It’s really not. In fact, the opposite for you and I, isn’t it Paul? This was absolutely the door to me being well and stronger and more positive and having this amazing life that I have now.

So this is not a one way street with no light at the end of the tunnel. It can be a really positive, life changing for the good approach to take. So yeah, I’d love people to know those things about therapy.

Paul: Thanks for that. I really appreciate those final words. I think people watching will realize it’s not a sign of weakness to seek therapy. It’s actually strength.

Hannah: It really is. Yeah.

Paul: It really is. It takes a lot of strength to do it. It takes a bit of strength to begin it, but as you progress, it gets easier and you become a much healthier person.

Hannah: You really do and actually you’ve touched on the best bit, honestly. The hardest bit is probably writing that email or text or whatever to a therapist and then going to the first session. That probably is the hardest bit. And I promise after that, pretty much for me, you and all my clients, it gets easier from there on. It really does.

So yeah. Get through that really horrible first bit and it gets better.

Paul: It really does. And I speak from experience when I say that.

Hannah: Yeah. Me too.

Paul: Hannah, it’s been amazing. Thank you very much for joining us tonight. We will include your contact details. I’m sure if anybody sees this podcast – obviously we’ll share your contact details – if they reach out to you, I’m sure you’d be happy just to speak to them as well.

Hannah: Always. And I think that’s what we try to make as accessible as possible. Just reach out, drop me an email, we’ll have a chat. No pressure at all. Let’s just talk through where you are and what options there are and we can go from there.

Paul: Fantastic. Thanks again for joining us, Hannah.

Hannah: Thank you so much for having me on.

Paul: My pleasure. Bye-bye.

Hannah: Bye-bye.

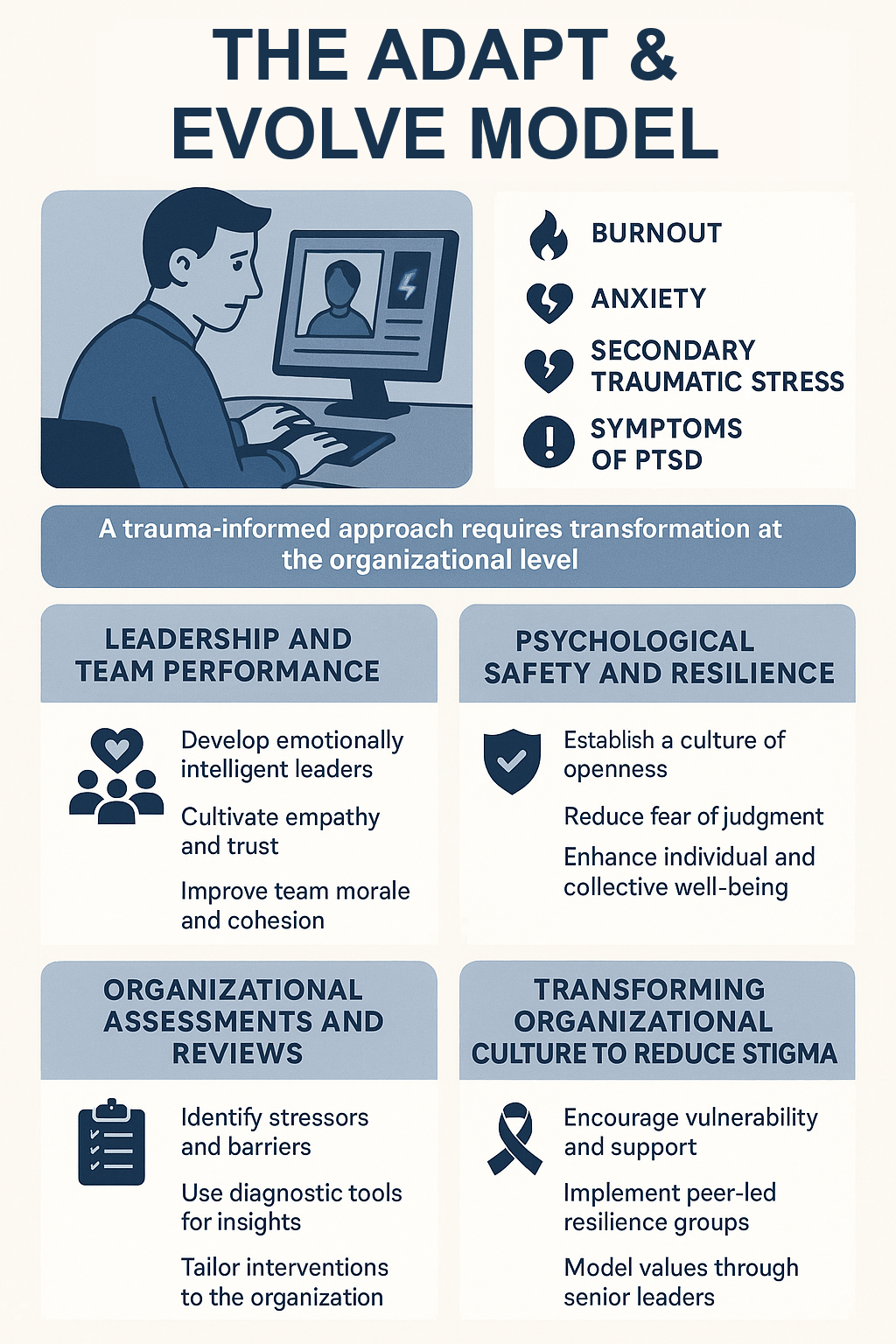

by Paul Gullon-Scott BSc MA MSc MSc FMBPSS

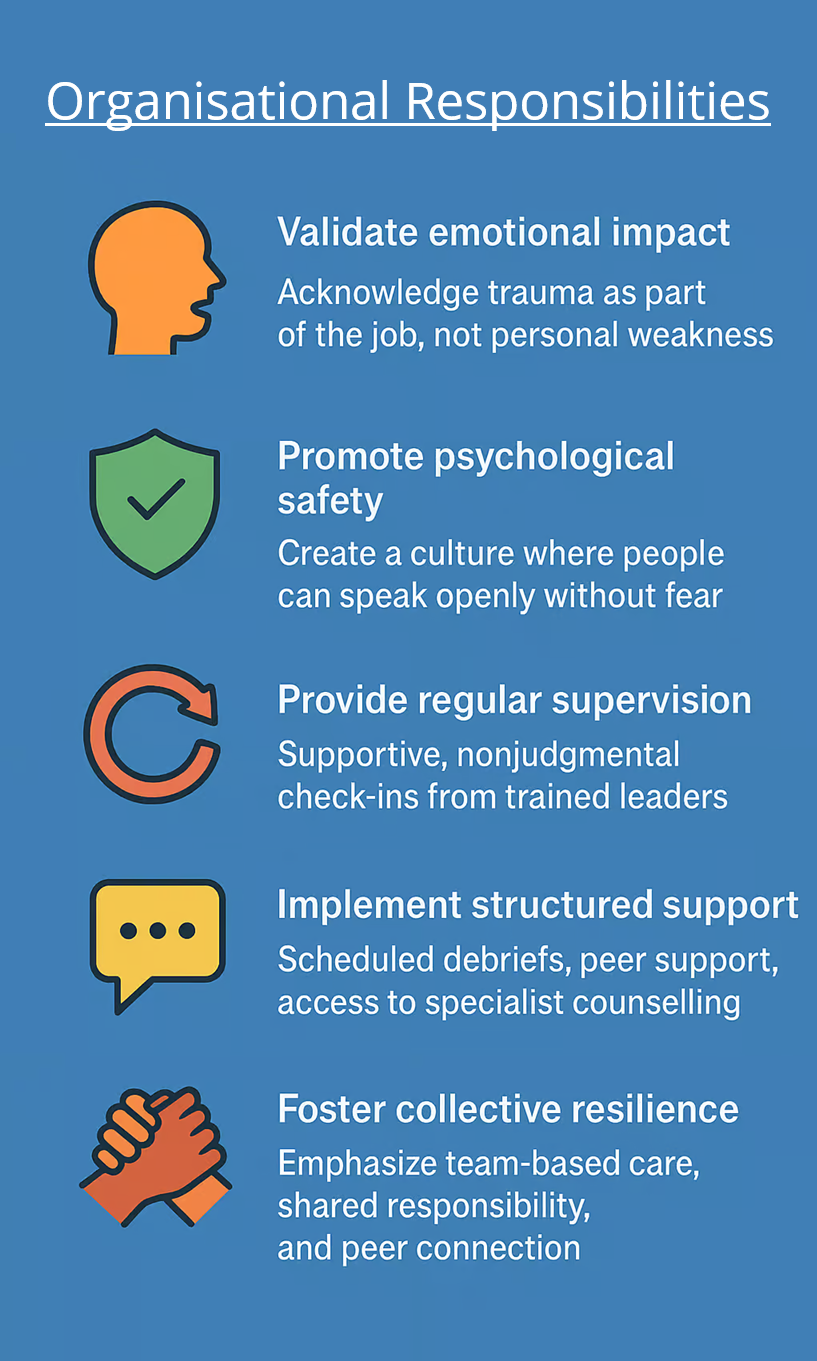

Digital Forensic Investigators (DFIs) operate under immense psychological and operational pressure. Their daily responsibilities often involve examining disturbing content, making time-sensitive decisions, and managing high-stakes caseloads. This relentless exposure to trauma and stress can lead to serious psychological consequences, including burnout, anxiety, secondary traumatic stress, and symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder. These challenges are often magnified by an organisational culture that lacks supportive leadership, suffers from poor team cohesion, and perpetuates stigma around mental health and help-seeking behaviours. Addressing these systemic issues requires more than individual coping strategies—it calls for a trauma-informed transformation at the organisational level.

DFIs are routinely exposed to distressing material, particularly in investigations involving child sexual abuse material (CSAM). This exposure significantly heightens the risk of psychological harm, including secondary trauma and long-term emotional distress. Despite the clear risks, organisational responses have often been inadequate. Many DFIs report feeling unsupported by their leadership, working in environments characterised by unclear expectations and a lack of psychological safety. Additionally, cultural norms within forensic units frequently discourage openness about mental health, framing vulnerability as weakness and contributing to a climate of silence and stigma.

Adapt & Evolve, a UK-based consultancy, proposes a structured and evidence-informed model for transforming the culture of digital forensic units. This model integrates leadership development, psychological safety, and ongoing organisational assessment to create environments that support resilience and well-being, as follows:

Central to this model is the development of emotionally intelligent, trauma-aware leaders. Adapt & Evolve delivers bespoke leadership workshops that emphasise trust-building, clear communication, and authentic connection. These sessions encourage managers to cultivate empathy and demonstrate genuine concern for the well-being of their staff. By fostering a culture of openness and support, leaders can dramatically improve team morale and cohesion. Rather than viewing leadership purely as a directive role, the approach advocates for a balance between accountability and emotional sensitivity.

Creating psychologically safe workplaces is fundamental to mitigating the emotional toll of digital forensic work. Drawing on frameworks developed by Edmondson, Adapt & Evolve’s training helps organisations establish cultures in which employees feel comfortable expressing concerns and acknowledging distress without fear of judgement or reprisal. Psychological safety not only enhances individual well-being but also supports collective performance by reducing mistakes and encouraging collaboration.

In order to implement meaningful change, organisations must first understand the specific stressors and cultural barriers affecting their teams. Adapt & Evolve uses a suite of diagnostic tools, including anonymous surveys, structured interviews, and cultural audits to collect actionable data. These insights allow interventions to be tailored to the unique needs of each organisation, ensuring maximum relevance and sustainability.

DFIs frequently report that their leaders appear emotionally disengaged, focused solely on operational outcomes while overlooking signs of psychological distress. This disconnection undermines trust and reduces the likelihood that staff will seek help when struggling. Adapt & Evolve’s approach addresses this by equipping leaders with the ability to recognise and respond to stress and trauma within their teams.

Training focuses on empathetic communication, the importance of active listening, and the value of emotional transparency. As leaders begin to model these behaviours, they foster a more trusting and supportive environment, directly influencing team morale, retention, and productivity.

One of the most persistent barriers to mental health support in forensic settings is stigma. To dismantle this, Adapt & Evolve supports organisations in creating psychologically safe environments where vulnerability is not only accepted but encouraged.

Initiatives include establishing peer-led resilience groups and confidential support systems that allow individuals to access help without fear of career consequences. Equally important is the role of senior leaders in modelling these values when those at the top of an organisation share their own experiences and normalise mental health conversations. It signals to staff that seeking support is both valid and encouraged.

Organisations that adopt a trauma-informed approach stand to gain significantly in both human and operational terms. Staff well-being improves as burnout, stress, and emotional exhaustion decline. Teams report increased engagement, stronger cohesion, and greater job satisfaction. Operationally, the benefits are just as significant: psychologically safe teams make fewer errors, collaborate more effectively, and adapt more readily to change. Importantly, trauma-informed practices also foster a sense of shared purpose and organisational integrity, shifting workplace culture towards sustained well-being and excellence.

A truly trauma-informed digital forensic unit begins with a rigorous assessment of organisational health. By identifying leadership shortfalls and cultural barriers, the groundwork is laid for evidence-based intervention. Leadership development should be tailored to the specific needs of DFI teams, prioritising empathy, communication, and trauma-awareness.

Simultaneously, policies must embed psychological safety into daily operations such as confidential reporting channels, flexible workload accommodations, and scheduled well-being check-ins. Creating peer support structures and ensuring these are accessible, trusted, and well-publicised reinforces a culture of shared responsibility and mutual care.

Finally, continuous monitoring and refinement of these practices ensures that organisations remain agile, responsive, and committed to long-term improvement.

The mental health and well-being of Digital Forensic Investigators must be recognised as both an ethical priority and an operational imperative. The Adapt & Evolve integrated framework offers a holistic, evidence-based strategy for fostering resilient teams and supportive leadership. By embedding psychological safety, conducting thorough organisational assessments, and cultivating trauma-informed leadership, forensic organisations can move beyond crisis management and instead build cultures where well-being is actively protected and performance is sustainably enhanced.

Through intentional cultural transformation, DFIs can be supported not just to survive their roles, but to thrive within them—ultimately ensuring that the people at the forefront of digital investigations are given the care, respect, and support they so rightly deserve. For more on this topic, listen to our recent podcast with Adapt & Evolve.

Paul Gullon-Scott BSc MA MSc MSc FMBPSS is a former Digital Forensic Investigator with nearly 30 years of service at Northumbria Police in the UK, specializing in child abuse cases. As a recognized expert on the mental health impacts of digital forensic work, Paul now works as a Higher Assistant Psychologist at Roseberry Park Hospital in Middlesbrough and is the developer of a pioneering well-being framework to support digital forensics investigators facing job-related stress. He recently published the research paper “UK-based Digital Forensic Investigators and the Impact of Exposure to Traumatic Material” and has chosen to collaborate with Forensic Focus in order to raise awareness of the mental health effects associated with digital forensics. Paul can be contacted in confidence via LinkedIn.

The following transcript was generated by AI and may contain inaccuracies.

Paul: Welcome to Forensic Focus, the podcast where we explore the critical issues shaping the world of digital forensics and those who work within it. I am your host, Paul Golden, and in today’s episode, we are going to shine a spotlight on the growing area of concern in our profession: mental health and wellbeing.

Those of us who spent time working in digital forensics understand the toll this work can take. Exposure to traumatic material, high case loads, relentless deadlines, and the weight of responsibility all contribute to chronic stress, burnout, and sometimes long-term psychological harm. In this episode, we’ll be exploring an innovative way to address those challenges head on.

Joining me are two exceptional guests, Dr. Zoe Billings and Mark Pannone. Co-founders of Adapt & Evolve with unique and complementary backgrounds. Zoe, as a biologist and former senior investigator in road traffic fatalities, and Mark as a former assistant Chief Constable, strategic commander and crisis negotiator.

They have combined decades of frontline and leadership experience to create a service dedicated to enhancing resilience, performance and wellbeing in high pressure professions. Together we’ll discuss the origins of Adapt & Evolve, their approach to stress, decision making and team performance, and why services like this could be vital to supporting the long-term mental health of digital forensic investigators.

This is more than a conversation about coping. It’s a conversation about evolving and adapting and finding sustainable ways to thrive in one of the most psychologically demanding roles in law enforcement. Welcome to the podcast Zoe and Mark. We’re really pleased to have you here.

Mark: Thank you. Hi.

Paul: Hi, Paul. Thank you for having us. Thanks for joining. Zoe, would you like to begin?

Zoe: Yes. So Mark, in 2019, I noticed in North Yorkshire Police where I was working that we’d got a reasonably sized occupational health department. There was a lot of work going on there to reduce stress and look after people.

But despite their best efforts, we still had people off on long-term sick. We had performance issues and some retention issues in certain areas. My background, as you said, doctor of biology – did my PhD at the University of York and I’ve tutored A-level for over 25 years.

I looked at the wellbeing provision and it focused solely around the mental health aspect, which was great – there was provision for it. But I equate it that if you teach people to recognize there’s something wrong when they recognize it as a mental health concern, you’re effectively teaching them to recognize that there’s a problem with their car when the engine seizes. And that’s too far down the line.

By that time, you’ve got to go off work, you’ve got to get your car towed, that sort of thing. I look at the biological aspects of stress because stress starts to manifest itself in the body physically whilst your brain is still saying, “I’m fine,” and it’s still pretending to carry on because from an evolutionary perspective, that’s what we’re programmed to do.

It’s not our fault – that’s hardwired in. So by looking at the biological aspects of stress, that’s the biological version of teaching you what the dashboard warning lights on your car mean. So when they come on, you can take action, get it resolved, and then your car keeps working and you keep going, and hopefully you’d never get to that point where your engine seizes.

So the biological aspects of stress – the biological wellbeing that we deliver – is effectively early intervention and prevention for stress. It stops people hopefully getting to the point where they are affected by the mental health aspects of stress, by teaching them to recognize it at the earliest opportunity, and really crucially how to then mitigate it and how to deal with it with a really comprehensive toolkit.

Paul: I think you’ve beautifully put together something here, which I quite often talk about and which I’ve talked about in the past, and that’s approaching this from a preventative point of view as opposed to a reactive point of view. You obviously identified within your force that there was no psychoeducation, for example, around the stresses that you could become susceptible to. And that’s where you come from.

Zoe: Absolutely. And I was brave slash daring enough to deliver it to our occupational health department. That could have gone one or two ways, but they took it really well. And there was that sort of recognition and that light bulb moment for them that we’ve never thought about it that way. So it got their endorsement and then the assistant chief constable saw it, which Mark could probably fill you in on what they thought.

Paul: So what did the assistant chief think, Mark?

Mark: I joined North Yorkshire Police during COVID. And it was then that I met Zoe – had the pleasure of meeting Zoe. And I was so impressed with it that I actually mandated it for those departments that were really struggling with stress that I was responsible for.

So the digital forensics unit was one of those departments. They were going through the UKAS accreditation challenges at the time, and we had a high sickness challenge within that department. DFU was one – some of the departments that were quite highly stressed, high sickness, not great performance necessarily – got them to listen to Zoe, mandated them to hear what she had to say about how to identify stress within yourself.

On the back of that I saw an improvement in both the performance and also the approach – the sort of like the feel, the culture within those teams and the self support that then went on and the self challenge within those individuals was fantastic. Because they were talking now a new language of prevention, like you say Paul, rather than individuals who, when they go pop, having to leave the organization, leave the department and deal with the unnecessary harms that could have been prevented with a more improved, resilient-based approach, a trauma informed approach.

So basically I loved what Zoe did. And then on the back of that, when I retired I then started working with Zoe. And now we go around the world. We’ve worked with the FBI – obviously we went out with yourself, Paul, in Munich last month and work with organizations throughout the UK teaching them how to identify stress within themselves.

How teams can then work to support each other. And then importantly, identify what the problems are within an organization that’s actually stopping you from thriving as an employee and how you can help yourself and your family. As importantly, look after each other, monitor each other and check each other out to make sure that things are on an even keel. And if they’re not, giving them tools, techniques, tricks to actually keep themselves in that good place rather than dealing with the adverse effects of poor decision making and poor stress management if they didn’t know this language. It really works and that’s why I’m really passionate about it.

Paul: You’ve touched on a couple of things there, Mark, which I’d like to expand on. Firstly, as a senior leader, you saw the problem.

Mark: I did. And I think the problem is with police leadership – you get to a chief officer rank, senior officer, superintendent and above, and then chief officer. You are under a lot of performance pressures. You either impose those pressures as a senior leader on others, and you’re also subject to them yourself, wherever they come from – a police and crime commissioner, from government, from your own chief constable, whatever. And that is stressful. That is difficult for anyone.

But we put no effort in teaching people how to be resilient, how to look after themselves, how to identify if things are going wrong. And it’s virtually criminally negligent, I think, that as an organization like the police, that puts people into very difficult situations, which are very hard to deal with by anyone’s standards, and not really giving people the tools on how to manage themselves both psychologically and physically.

Then it’s a case of – why do we do this? If you’re lucky, you will survive and get to the end of your career and you’ll take a pension and you’ll say “Thank God for that, I managed to escape.” Other people aren’t so lucky, and there were many people who could have continued with really impressive careers without going pop if they’d had the tools to manage themselves. And it’s those tools that we provide people with so that they can be really the best performing and most resilient that they can be. Because unfortunately, that’s what is not currently taught within policing or many other organizations I’ve seen. And that’s the gap that we hopefully fill.

Paul: I have to say as a senior leader, having spoken to many DFI around the country, do you know how rare you are?

Mark: I think the problem is that digital forensic investigators have a niche role that no one really understands. And as a leader, you want to pretend you understand everything. But because it’s such a specialist area, it’s “oh God, I really don’t understand that. I know they do great stuff and they solve loads of problems for us. But ’cause I don’t really understand it, I don’t really understand what UKAS do and I don’t really understand the ISO – I’ll just crack on and speak to the boss and hopefully everything’s going fine.”

The trouble is that digital forensic investigators are a certain type of person. There are some amazing approaches that digital forensic investigators take. And there’s a mindset and there’s a culture within DFI. The trouble is there are some problems that I have seen consistently across different digital forensic units.

And sometimes it’s about people feeling that they’ve got a voice. And I think one of the most stressful things for a lot of digital forensic investigators may not actually be the material they’re looking at – it may be – but it may actually be the fact that they feel that they don’t have a voice, they are not listened to. They’re not necessarily seen as part of the investigative framework team – part of the team.

And quite often we’ve seen this ourselves – the frustration caused by not even being notified of results in court that they were absolutely key in and pivotal in getting. That’s very stressful and it makes people feel not as valued, not having as much worth as maybe they should have. So I think we really need to recognize the type of people that work in DFI and what drives them, what motivates them and what they need.

And that’s why we go into some detail trying to really analyze what it is that the stresses are for them. And not make assumptions about what’s stressing people out, but by giving people the tools to be able to articulate, “oh, that thing is, yeah, that and that” – is it about the workplace? Is it about the kit and technology? Is it about the people you’re working with? Digging into it further, we can really help them articulate what actually is causing them problems and helping them on that journey, and then help them to address those stresses themselves.

Paul: I completely agree. It’s not just one thing that stresses DFI out. It’s not just the traumatic material. You’ve got organizational pressures, you’ve got deadlines to meet, you’ve got pressures coming in from the CPS and it all adds up. It all has a massive effect on the mental health and wellbeing of DFI who are out there at the coal face. So let’s talk about – can we talk about the proactive approach that you guys use to try and lessen the effect of the stresses borne by DFI?

Zoe: So if I kick off Mark with a bit about more about the biological wellbeing – DFI, police as a whole, law enforcement as a whole, we deal with facts and DFI very much so deal with facts, hard, cold evidence, et cetera. And so when we focus on the physical aspects of stress and say actually what actually is happening in your body and the science behind that, the evidence for that, it is an approach that really resonates with them.

Biologically our autonomic nervous system – we share that in the same pathways with all of the mammals. We share it with the birds, and we have the same pathways that the dinosaurs had, and yet we are the only species that will have stress as a comorbidity factor, because we are the only species that has that problem. And yet it’s just the same pathway as every other species.

So it’s a case of, okay, why – what’s making us different to everybody else? It’s that we use that pathway differently. We explain to them and it’s done in a really fun way. You don’t need any science behind it. It’s translated itself across, as Mark said, when we worked with the FBI, all the jokes, et cetera. It was brilliant. But yeah, and it’s a fun, engaging way of communicating the effects of cortisol, the stress hormone on the five whole body systems.

So we cover the musculoskeletal system. We cover the cardiovascular system, the gastrointestinal system, immunological system, and then fertility and sexual function and all of this – the early warning signs, the sort of dashboard lights that the body will put on in those systems that people will sit there and you can see it in their faces and they’ll be like, “I’ve got that, I’ve got that, I’ve got that.” And it’s about joining those dots up.

And once they’ve understood the science behind it, they’ve understood why their body is behaving in the way it is and why it’s not performing like it should do, and why they’re suddenly intolerant to foods that previously they’ve enjoyed, but suddenly onions are giving them gastric challenges, but they don’t understand why. And when you’ve given them the power to understand actually – yeah, okay, that’s why it’s happening – and the ability to identify that.

And then as Mark leads with the toolkit of 18 or 19 now, scientifically proven techniques that cost nothing that everybody can do to reduce their cortisol levels, to address their stress and resolve those symptoms and the impact of it. The feedback from it is incredible and the change that it makes to people is incredible. Over 3000 people have experienced this workshop so far.

And in one of our early workshops, we worked with a CEO as a quick example – medicated for high blood pressure and we teach the cardiovascular system. We teach what high blood pressure is, why stress gives you high blood pressure, what cortisol is trying to do when it increases your blood pressure, but then scientifically proven ways to reduce it.

Now three to four months after experiencing our workshop and committing to doing the activity that we’d said daily, just five minutes at a time, that’s scientifically proven to reduce blood pressure, that CEO had a medication review at the GP and was taken off their blood pressure medication.

Paul: That’s amazing.

Zoe: And that’s – yeah. When you understand exactly what high blood pressure is, how it leads to cardiovascular disease, how it will kill you, it will ruin your life, it’ll curtail your life. And in fact, they updated me last week in an email just talking about something else and said, “oh, by the way, this is over two years on now. Just had a blood pressure review at the GP and it was perfect.” And that’s medication free.

We live in a society, I think, very much in the western world where we’ve got that learned helplessness, where we have to have a tablet to fix something. You don’t. And actually, if you can remove a symptom entirely from your body rather than trying to treat it while it’s there, just by increasing your knowledge and then understanding and proactively encompassing scientifically proven things into your life to make yourself healthier and better able to perform without any medication, then that’s brilliant.

There is a place, I will just say, there is a place for medication and I would never encourage anybody to come off medication. That’s for their GP to review. But if you put yourself into a position where you don’t need it, that’s gotta be a good thing.

Paul: It absolutely has. You guys come at this from what I think is a really unique angle because we know the stressors that DFI can succumb to and the mental health effects. What there isn’t out there is a big block of research, which says, as a result of those mental health stressors, these physical ailments can come from them. And that’s where you guys come in. You guys have identified the fact that because of these stresses, DFI and others in high stress professions can then become physically ill, not just mentally ill, but physically unwell. Do you want to talk about the physical ailments that can come from this?

Zoe: Certainly. When we look at the musculoskeletal system, tension headaches, which people would expect, increased risk of migraines, neck pain, shoulder pain, but the one that people don’t understand – lower back pain. Cortisol causes your muscles to be held in tension. Your lower back hates being held in tension, and you’ll get lower back pain, but very often, and it was amusing to see that it is treated in the same way in the US as the UK.

We’ll get people a special chair and we’ll treat the symptom, but we won’t treat the cause. As I’ve mentioned, also high blood pressure because we’re trying to deliver oxygen and glucose to the muscles more quickly ’cause the brain really does believe there is an imminent threat to life. And all the associated increased risk of cardio events – so heart attacks, strokes, pulmonary thromboembolisms, where you get blood clots in your lungs, et cetera. Deep vein thrombosis, things like that.

The gastric system that relies on having a really good blood supply to function properly. And yet when we divert all the blood to the muscles because the brain thinks there’s an imminent threat to life – I’m gonna have to run or fight – it shuts the gastric system down. In the gastric system, you are still putting food into it, but you’re not giving it any of the blood and the glucose that it needs to actually make the energy to digest the food. And then you’re wondering why it can’t digest the food. You’re saying to it “go,” but I’m not giving you any fuel.

So you get things like stomach ulcers, can resolve indigestion, inflammation, temporary food intolerances, irritable bowel syndrome, colitis if you’re really unlucky, ulcerative colitis and things like that. Obviously the bloating and the discomfort and then things like your immune system that gets suppressed by cortisol as well.

You get an increased frequency of colds, of other illnesses, things like that. There is an increased risk of cancer ’cause your immune system is there to look for altered cells as well. As well as autoimmune conditions, as I’ve also mentioned already, ulcerative colitis – that’s autoimmune. Eczema, Crohn’s.

For many years they thought that they knew that cortisol exacerbated those symptoms, but it’s only relatively recently that evidence has come to light that actually says that cortisol can be a causatory factor. So actually being chronically stressed can instigate these autoimmune conditions ’cause your immune system gets so suppressed it goes a little bit haywire.

And then you’ve got also things like if you carry dormant viruses – Epstein Barr, that’s glandular fever or herpes, that gives you cold sores. If your immune system’s suppressed, you get an increased likelihood of them reoccurring, shingles, those sorts of things. All those dormant viruses that can live within us. Fertility and sexual function – erectile dysfunction in males and in females, disruption of either ovulation or menstrual cycles or both.

And it’s quite – when you let the body recover, when you remove these stresses, it’s really amazing how quickly those symptoms can disappear without any medication because you’re just letting the body do what it’s built to do.

Paul: You’ve just made me smile when you were talking about lower back pain. I remember when I was working as a digital forensic investigator, one of the things I really had was lower back pain, and I never connected the two until I heard you guys speak in Munich and I was sat there smiling away at myself thinking, “yeah, that’s why I don’t have lower back pain anymore.” Because those stresses that existed back then aren’t here now. And I don’t suffer from it, but I would never have connected the two had I not heard you guys speak.

Mark: And you’re not unique there, Paul. People do not connect what’s happening with their bodies with the fact that these could be stress related symptoms. And all we are doing is basically making people aware of what the science is behind stress, the effects that it can have and then looking at ways to address them. So I would like to think what we’re doing isn’t absolutely radical. It makes absolute sense, I think you need to have a specific knowledge of the science to be able to do this credibly. And that’s where Zoe comes in.

And then be able to, when you understand if you are stressed, then decide what is it that’s causing me stress and be able to address that issue? So linking your biology to stress a bit like Zoe’s analogy of a dashboard on a car, seeing what those warning lights are and understanding them is the very first thing, and that’s really the great teaching that Zoe does.

It’s then just a case of then working out what’s causing the stress, how to address that cause, as well as how to manage your own stress response better. So when you put all that package together, I think that’s what probably sets us apart from others because we are really delving into the why are you stressed and why is your body acting in a certain way to be able to then address the cause and not just the symptom.

Paul: I think also, and I really want to highlight this, the other thing that really sets you two guys apart from everyone else is the fact that you are culturally aware of the problems within forces. And I think it’s really important to highlight that. We saw a perfect example of why this is important in Munich.

When one of the delegates was talking, he explained they used to have a psychologist who came into the unit where they’d sit and they would have group discussions. And when I probed why it turned out that because that psychologist wasn’t culturally aware of the work or the stressors, et cetera, when a member of the team disclosed a particularly difficult case, the psychologist broke down and left and never returned. So to be culturally aware of the nature of the work and the operational stressors, I think is a massive value.

Mark: I think you’re right. Because people who work in law enforcement, invariably they don’t suffer fools gladly. They are prepared to call out worthless support in inverted commas. And we’ve all been there when we’ve seen wellbeing sessions which really haven’t been of any great use whatsoever.

So to be able to recognize and understand the stresses, to really appreciate the things that cause people most frustration, which may not be the material they’re looking at. It may be their supervision, it may be the shift pattern, it may be the organizational culture. And because we’ve been there for over 50 years between us having seen very good support and shockingly bad support then, we can get rid of all of the stuff that would be a barrier to us being able to engage with people properly and also when people I think are just saying things for the sake of saying it, we can call it out as well a little bit.

So the game players that you do have, because they want to do whatever. My 31 years of policing in a leadership role was about smelling the stuff that was put on flowers to make them grow nicely. And actually be able to say, “come on, that’s really not what the issue is – something else here.”

And that’s why we like looking at psychosocial risks around organizations. And really digging into them and understanding those pressures that people have within their organizations. And that’s why we really started to see themes and being able to tease out those themes in people, especially around communication and barriers of communication within the organizations, which really frustrates DFI because they do not feel they’re being listened to effectively, or suggestions they’ve put forward are not being heard.

So what is it about the way that they’re approaching the subject that’s stopping them being listened to by more senior management? And that’s a really interesting area.

Paul: It is. It absolutely is. And it’s frustrating for DFI because as you said, they really do feel unheard. Many of them have asked for more supportive mental health provision, and it just doesn’t come. Despite the ever increasing workload which is placed on DFI, the mental health provision has stayed static. And it stayed static for years and years, and that’s just not sustainable.

Mark: So the solution there is to do what we do, which is to go into organizations and we use the ISO 45003, which is basically looking at the psychosocial risks within an organization. So rather than, for instance, looking typically people look at health and safety from the perspective of physical risks, slips, trips, falls, all that sort of thing. You are much more likely to go off sick ’cause of the psychosocial risks.

And so we will do work with the DFI to identify what those psychosocial risks are and provide a report back to the organization and we’ll make it quite clear to say, “look, these are definite risks to the health and safety of your staff. If you do not address them, then as an organization there may be some questions asked at a later stage such as in employment tribunal, and wherever else?”

So you can use a stick to actually support this work. And when we’ve worked with organizations, we really have encouraged them to have a much different approach towards communication, towards line management, towards workflows. By actually using the psychosocial challenges and recognizing that they will get improved performance, they will get lower sickness and they will stop having to worry about retention issues by actually providing this support. Carrot and stick in the same way.

But the reports that we will provide and, we can do this over an afternoon, it’s not a difficult piece of work. We can provide an organization with a way of making sure that your DFI are working to the best of their abilities in a sometimes in a very cheap and easy way. Just by tweaking how the DFI are respected and recognized as part of the organization.

Paul: I think you, again, you touched on something really important there when you mentioned the ISO standards with regard to health and safety and wellbeing. I think many employers need to recognize that they have a legal obligation to their employees. I know police officers aren’t classed as employees, but they still have that legal obligation to protect them when it comes to wellbeing and mental health. And obviously you based your model, your services on those ISO guidelines. So it’s as good as it can be, isn’t it?

Mark: I think the ISO around the psychosocial risks that affect you in the workplace – I think it’s best endeavors. It’s the best model that’s out there, I think in looking at how to support your staff. I don’t think it’s perfect, but I think, and I can talk with experience of having been the employer at an employment tribunal where it’s not an easy ride.

But if an organization has shown reasonableness, fairness, and has deliberately gone to look for the problems and then try and resolve them. Most judicial processes will look very favorably at that. And so that’s what we are saying to organizations. We’re saying, “look, bring us in. Let us speak to your DFI. Let’s work out what it is that’s causing them problems, be it how their work is organized, be it their work environment, their equipment, or the tasks they have to do, or maybe the social factors that work.”

Looking at all of these, get them to identify what the problems are. Most importantly, identify solutions to those problems. And then organization, chief constable, chief executive, police and crime commissioner, health executive, whoever, you can then decide how to deal with those issues to make sure that people are working effectively and not then going off stressed. It is a very good business reason for doing this.

Not least the legal problems, like you mentioned, Paul, of if you don’t do this, if you are refusing to listen to people, then that could get you in quite a bit of trouble as well. So there’s good business reasons as well as good human reasons to do this.

Paul: Yeah, there absolutely is. Because obviously, the risk is that police forces could ultimately end up getting involved in litigation having caused such significant mental health problems.

Zoe: Absolutely, and I think, just saving money on the physical support that they then have to give officers and staff. When you look at the cost of, when people have their back pain, they have that special chair that they get bought – just as a daft example, we’ll treat the symptom, not the cause. Those special, better chairs cost 1200 pounds each. So what’s 1400 Euros? That’s about $1,600.

And if you’re not addressing the cause but you’re just treating the symptom, it won’t solve the back pain. And actually it’s a worthless investment. If you, and we recognize that a lot of forces, there’s a lot of financial pressures on everybody around the world, so therefore it’s even more important not to do wellbeing washing, not to get the wrong people in, not to waste investment on special chairs, when actually if you invested in the cause of the stress and resolve their back pain, they wouldn’t need additional lumbar support because it’s not a postural problem.

Then you actually will see the benefit. And I think, Deloitte said that for every one pound invested in meaningful wellbeing, you get a five pound 60 return. And that word is the one – it’s meaningful. And I think the culture has been, the wellbeing space is quite crowded. There’s been a lot of people making a lot of money historically for saying, “oh yes, I understand why you are stressed, et cetera. Here’s a stress ball and have you tried sleeping?” And a very holistic approach that hasn’t been resonating with people, that’s really made a lot of people particularly I think law enforcement people, people working in that area that look at evidence a little bit skeptical around it because they’ve had so much poor intervention by people, like you said, that don’t have that credibility, that don’t know their world.

And I’ll just, as a very quick – we were working up in the north of England and I’m not gonna swear on a podcast, so I’m gonna edit one word in this, but I overheard an inspector and he said, “oh, what’s this wellbeing rubbish we’re having this morning.” And I heard that before we were going in to deliver the biological wellbeing to them. And I thought, “game on.”