Si: Welcome. This is the Forensic Focus Podcast. You’ve got Alex and I again for another week running and we don’t know what we’re doing, so we will be rambling at you. But welcome to listeners across the world of which we have and we have them on Spotify and downloading from the Forensic Focus Podcast section of the website. So hi, guys. Welcome along to us. We do actually have, Alex was kind enough to come up with a topic of conversation this week.

Alex: More than five minutes before the show, as well. It was all planned out at least four hours this time, so you know it’s going to be good content.

Si: So yeah, I mean, you sent through a link talking about training and certification.

Alex: Yeah. So I guess like, we’ve wanted to talk about, I guess, training in the cyberspace and certifications and there’s probably like a whole in-depth topic we can go into about different training organizations and the way it’s been.

But in the news this week a company that I used to work for, CyberCX, has announced that they’re doing a, I think it’s a partnership with the federal government even, where they’re training 500 security professionals from, I guess, nothing to something over the next 12-24 months.

So I thought it would be a good time to talk about the different training pathways that people could take to get in, what we think about them around this kind of thing, and I know other consultancies in Australia, so the Big Four are all kind of gearing up their own internal academies, particularly around cyber.

So that’s across all the spaces in terms of like GRC, pen testing, DFIR to have a pipeline of people coming into the company because there’s still across the world is massive skill shortage. And what better place to train people than on the job?

So yeah, I have some opinions on that. And some pins on traditional training, the training that I guess I went through which is more the certification pathway. Yeah, I guess the start with like, in your country, are you seeing kind of companies like Big Fours and that gearing up to train a pipeline?

Si: There’s always been some sort of pipeline for bringing people in into the Big Four sort of consultancies. A friend of mine, an acquaintance, well, yeah, a friend, yeah, I know him, it’s fair enough, I haven’t spoken to him in ages, but he’s a friend, years ago he asked me to review his master’s thesis because he was doing a master’s thesis on forensics. And I just did some peer review of that before he submitted it.

And he went into one of the Big Four in Ireland and he went in with a master’s degree in forensics, but then was further trained into doing forensics in that sort of environment, in that very specific the things that they were looking for. So, and, you know, I’ve known him for, you know, 15 years. So, you know, it’s been around for a while. It’s not new for us.

What we’re seeing is quite a lot of, there’s been some advertising from sort of GCHQ and various people suggesting that cyber is, because there’s this skill shortage, because there’s a shortage of people wanting to do it, that this is the way you should take your career, that you should do this.

And, you know, advertising that, oh, this famous advert actually, I don’t know if you can screen share on Zoom, sorry, bear with me, and I’ll have a little play in the background, but, you know, there’s a ballerina taking her ballet shoes off and then the caption is “Her next job could be in cyber.”

It’s been parodied so many times with some varied suggestions for the Prime Minister that he could get, you know, or the ex-Prime Minister now that he can get involved.

Alex: I think that that’s a sign of good marketing, right? Like, when you’ve got the attention of people to parody it means that like, it’s that old saying like, “all publicity is good publicity.” Like, you always come back to knowing that that came out from GCHQ and that was the ad, even if you’re parodying it.

Si: Yes. Yeah. So hang on, let me just…

Alex: I think, I can’t remember, but it was potentially like, and this could be a decade ago, but I think it was GCHQ or somewhere in the UK, like a cyber body that was training. They had a cyber skill center for high school students. And the whole aim was to catch, I guess, the youth that was growing up in cyber before they were turning into criminals. Was that GCHQ that was running that? And they had like an actual walk-in center that you could train at.

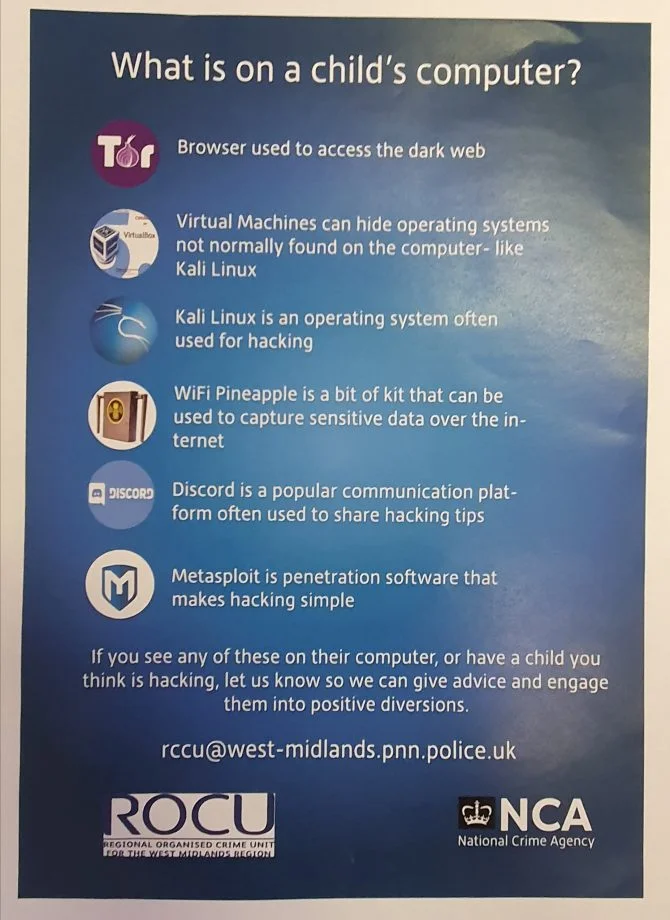

Si: I’m not sure about that, but they sent out this fantastic list not long ago, because we’ve just come into school summer holidays here, is was the list of, “If your child has these tools on their desktop, they could be into hacking and you may want to talk to them about it.” And I was reading the list and I was like, yeah, actually, if they’ve got those tools on their desktop, yeah, they’re probably on their way to quite a good career. I think it’s probably a good idea. So hang on here.

Alex: Watch out. They’ve got the command line open and they’re running IPconfig.

Si: Yeah, that’s it. Sorry, it’s a Mac and therefore it’s asking permission to do absolutely everything.

Alex: So, while you are bringing that up, I did read a bit more of the article. So it was 500 security professionals over the next three years they’re aiming. And it was announced at Parliament House by one of the cyber ministers. But yeah, like, I think having this kind of pathway and having on-the-job training is actually really good. “Her next job could be in cyber.”

Si: Yeah. And, I mean, Downing Street enjoys criticism of crass job ad. I mean, let’s be honest, Downing Street couldn’t know crass if it came up and bit it on its backside. But yeah, the rethink reskill reboot kind of mentality, it’s been, what date was this? 2020. So, you know, two years back.

Alex: I don’t understand why people thought that was a crass ad, though. Like…

Si: I think, let’s have a look.

Alex: Like, I don’t know, like, I don’t think that would translate. So for the people who are just listening, the ad just has a ballerina sitting in a chair doing up her shoes. It says, “Her next job could be in cyber.” And then in brackets, it has, “She just doesn’t know it yet.” And it’s got government branding on it and it says, “Rethink. Reskill. Reboot.”

Si: I think the issue is highlighted here. And I, again, you know, for the listeners who are just listening and not watching, “Critics on Twitter called the advert patronizing, saying it showed the government was not helping the arts through the pandemic.” which is entirely true. The government didn’t help the arts through the pandemic.

Alex: So it was more a comment on if that wasn’t an arts job and it was another industry that was supported then they probably wouldn’t think it was crass.

Si: Part of a campaign, encouraging people from all walks of life to think about a career in cyber security. And then I want to save jobs in the arts, which is why we’re investing £157 billion. I mean, I think…

Alex: I think if they put it out as an ad campaign with a lot of different jobs and the same message, then it’s probably less targeted.

Si: It’s not though, it’s just cyber and it’s, to the best of my knowledge, I’m going to say I remember this is two years ago and my brain has been addled by two years of COVID since then. And I’m more jaded than usual. The various parody versions of it, I’m a huge fan of, I have to admit.

Alex: So there’s another one there with Boris Johnson with the bottom half of a ballerina in a pink Tutu that says, “Boris’ next job could be in ballet. He just doesn’t know it yet.”

Si: “Rethink. Reskill. Resign.” is the subtitle. Anyway, I digress and show some…

Alex: I missed the resign. That’s awesome.

Si: I was going to say, I think that’s another genuine one is showing a young lady stacking jeans on a shelf in a retail environment and it’s, “Sophia’s next job could be in cyber.”

Alex: Yeah, yeah.

Si: So there are varieties and variations on the parodies of these. But certainly there’s been a move to (I hate Zoom, how do I stop sharing?) Anyway, there’s been a move to recruit. But anyway, so we’ve had this concept of skilling people into cyber, and actually quite interestingly in the past, I’ve worked with a lot of guys who’ve come out of the MOD.

Alex: What’s the MOD?

Si: Ministry of Defense for everyone else. And they’ve come out after serving for a number of years in certain roles. And one of the skillsets they’ve been pointed towards has been cyber. And then they get their training as they leave and they get paid for certain courses and things.

And I’ve thoroughly enjoyed working with all of them because they tend to have very good stories to tell. And certainly in various areas of cyber they’re very well-skilled and certainly in risk management, they’re very, very good at risk management. They’re used to understanding the concepts of risk as to whether somebody’s going to blow your head off or not.

And applying that into a cyberspace, well I tend to find or, and I don’t mean any disrespect to anybody I’ve worked with previously, is that the fundamental technical skills are lacking. So they tend to operate on a slightly higher level, but actually in risk management, that’s not necessarily a huge disadvantage. As long as you’ve got good technical people to back you up, that’s something you can deal with.

Si: There’s another company in the UK that was set up quite recently that is aiming to roll out skills in cyber and get people up to it. But my concern about all of these and this idea that cyber is, I mean, it can be a very well-paid industry. Let’s not knock it. You know, there are some high paying jobs out there. Not knocking in forensics people, I’m sorry about that. But in cyber, as a field, there are some very high-paying jobs that work very well in.

Alex: I think even if you look at, and I don’t know whether this is the same across the UK and the US, but at least in Australia, I would say the average salary in cyber is higher than other general jobs. Even if there are a lot of jobs that probably don’t pay as much as some others, at least the base salary is higher.

Si: Yeah. So it’s being sold as a good industry to be in. And because there’s a skill shortage, people will get employed. My concern with it is that actually, and with the number of the courses as well, is that I feel that there’s a fundamental lack of base knowledge that isn’t being taught.

I can go to a course and I can be taught about risk management, for example, again, you know, picking on that one, the unfortunate field of risk management. That doesn’t tell me how TCP/IP works, it doesn’t tell me about underlying network structure, it doesn’t tell me anything about the way that the processor will execute commands or any of those fundamental low-lying computer skills.

I mean, my background is computer science. I was a systems administrator. Actually, what’s your background with regards to computing? I mean, he says before he slags off the fact that I walked into this manual course on, yeah.

Alex: Mechatronic engineering and mathematics, so more like microcontroller logic that I had. And then it was just a hobby interest in programming languages and electives that I did as part of my degree. And then I’ve purely been trained into that from either on the job or kind of courses or certifications that I’ve done in my own time.

So, yeah, but I can definitely see, like, I can agree in the technical fields within cyber that still, and like, personally, I think if you were going to go get a degree, then computer science is probably where you’d go still to get that real foundation. Or even computer engineering it’s called at some universities.

Si: Yeah. There a variety out there. Isn’t there. So you have computer engineering, computer science. The course I was teaching on was actually cyber security, but the first module that I was teaching was operating systems. And we started with, you know, what is a chip? How does it process this? We talked about memory allocation and stuff that was very much a computer science course in that regard.

So we were looking in detail at that. And then, okay, yeah, we were approaching it with the view of a cyber mindset. So talking about things like buffer overflows, but in order to know what the buffer overflow is, you need to know what the buffer is in the first place and why you would want to use a buffer and what the buffer actually solves it with regard to the fundamental problems in confusing.

So, you know, we ran quite a heavy technical-based course on cyber. Interestingly, on the master’s course it was a lot harder. It was easier to teach the undergraduate students because they all came in after A Levels in the UK, so they’re coming at about 18, give or take six months. And they’ve just finished doing, we specialize in three or four subjects for that set of exams.

So they’d usually done maths, a science, a couple of them had done English and some interesting sort of variations. It tended to be relatively scientific people with a mathematical bent. So we could be quite good with them. Whereas once we got to the master’s courses, actually the backgrounds that were coming in for the master’s courses were occasionally less technical even though they had a first degree.

And then our undergrad students were, and especially when we took a lot of overseas students and various things, and we would roll out and say, “Okay, well here’s a Linux box, let’s start doing some forensics.” And they were like, “What’s Linux?” Yeah. And that sort of lack of technical background actually started to become a bit of a problem when you’re spending time teaching people how to use Linux before you’re teaching them to do something with it.

Alex: So it’s really interesting in the way you’ve described the degrees that it’s kind of a computer science degree with a cyber flavor, even though it’s called like the undergraduate degree that you were describing, because it’s very technical-heavy.

And I think in Australia, a lot of the cyber degrees are trying to cater to the broad spectrum of cyber security, which does range from essentially risk management all the way down to that really technical, if you’re looking at saying digital forensics is on the technical end of the spectrum where you need to really know your stuff on computers, and it’s only a three-year degree.

So you’re trying to pack a full breadth of knowledge, which is great. It gives you base knowledge across everything, but probably not enough to be great, or even to start at any one thing.

Whereas if you look at, so take, for example, my degree, as a double degree, it was a five-year degree, and as a single, it was a four-year degree, and the first two years were generalized. So it was all the subjects that all the first and second years did.

And it was even broad in terms of engineering. So I did like statics, which was like lever beams and that kind of thing; dynamics, so planetary orbits. I even learned the different phases of iron metal, like when it was melted which I’ve never used again and I thought that I was a waste of a subject.

Si: Oh, hang on, as you transition career to a blacksmith there, don’t worry. It’s coming up.

Alex: Well, I’ve got a whole other spiel on blacksmithing in Australia because there’s not many of them. But in my last two years, that’s when I specialized in mechatronics. And the department that I worked under at the university was a working company.

So we were getting educated by people who were in the industry currently, like working in mechatronics. So our university focused a lot on agricultural mechatronics. So they were building robots to go up and down the lines on farms, to spot-spray weeds rather than crop dusting the whole thing and killing a lot of wildlife.

So those projects, sometimes people got to work on those or they just got to work with practitioning, mechatronic engineers, which was awesome. And it made the degree so good in those last two years and especially to do your thesis under those people.

And so in your example with your cyber degree, I think that’s perfect, right? because it’s more focused towards the technical streams themselves because you’re getting that technical underlying thing.

And that’s great if that’s where you want to go, but potentially someone who is in GRC, while they’re going to get a lot out of that, it’s less of the risk management skills that they probably need that they would’ve got doing say, a business degree and they’re just chucking cyber on top of it.

So yeah, I think for most degrees that at least within Australia that I’ve seen, that’s the biggest issue. Is it too broad? There’s nothing that goes, “Here’s a four-year degree and you major into digital forensics or you major into pen testing.” And it covers that more technical stuff in the pointy end of your degree, which is challenging because then you’ve got to convince people that they should start doing a four-year degree rather than a three-year one.

Si: Yeah. I mean, I agree with you in that regard, certainly when it comes to training for forensics, because, I mean, we did a module on forensics and so we have, I mean, the module is what, 10 weeks of training with having them lectures a couple of hours a week and then they have coursework.

I will be brutally honest, I did most of a master’s degree in forensics. I didn’t finish it for various disordered reasons, partially because I started teaching courses on it and it got a little complicated. But, you know, my introductory course, my first course was a two-week long, 9-5, Monday to Friday, in Shrivenham just down the road from me at the Royal Military College of Science and Cranfield University. Literally, I sat in a lab for eight hours a day for 10 days to do the introductory course.

And, you know, the undergrads that we had and we gave them a course, and to be fair, the undergrads was digital forensics and incidence response. So we covered off incident response as well. Which again, it’s a different field to digital forensics. It’s not the same thing. We had to cover off how incident, you know, it’s…

Alex: A lot of overlap, but definitely…

Si: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Definitely different. And we crammed all of that into, well, we crammed a lot into 10 weeks and at the end of the day, the conclusion was that actually what we needed to teach them was a mindset about learning and a mindset about experimentation and how you approach finding out what the heck has gone on. Okay, whether that’s in forensics or incident response, fundamentally what we are trying to do is go…

Alex: It’s still the scientific method, right?

Si: Exactly.

Alex: Even though it’s computers, you still form a hypothesis, test it and then give your conclusion and results at the end.

Si: And that, for me, is what is required in forensics and that’s what’s required to be a good forensic analyst. And if you disagree, say so, but I suspect it’s what’s required for a good incident response person.

But when we look at certification as a whole, what we are seeing is, can you answer a bunch of questions that you have learned by rote, generally speaking? And/or if we’re talking about vendor certification, can you use a tool to get results? It doesn’t actually capture that underlying requirement to, well, be inquisitive for a start. You know, I pressed the button and I got a bunch of results. Great. My reports are written, I can send it off and I can invoice for it; versus, okay, I need to understand what’s going on here, I want to understand what’s going on here.

And I think that’s where, for me, certification falls over. And, I mean, I say this, I have some certification. I’m a CISSP, so certified information systems security professional, the sort of industry standard. I’m not going to call it base level because it’s not, but the industry standard for information security consultant type activity.

But the exam is a six-hour multiple-choice question, 300 multiple-choice questions over a six-hour period. And it is about, have you learned this? Not, have you understood it? It’s about, have you learned it? And okay, there is a requirement that somebody needs to sign off on your experience and needs to say, in my personal experience and without wanting to upset ISC2, who are the guys who run this, that sign-off is not as stringent a control as they would like it to be.

Alex: Right.

Si: So I know people who basically have sat the exam who have written to someone who they know who’s a mate and have gotten them to sign off on their capabilities. I’ve signed off on the capabilities of people I have worked with who I have respect for and I know to be good.

But other ones I know who have very little experience suddenly have a CISSP. They’ve learned the stuff, don’t get me wrong, but there’s a big difference between learning and understanding. There’s a big difference between that experimental mindset that we are looking for.

And this is a criticism of education as a whole actually, in some places — the UK included — is that we teach children to pass exams. We don’t teach children how to learn. We don’t teach children about the excitement of life and the joys of scientific exploration. We teach them that if you write this down in answer to that type of question in an almost algorithmic response.

I mean, I could teach a computer to pass exams on the basis of, you know, what they’re asking for. (Good God, have we been talking for an hour already? Zoom’s telling me that we’re running out of time.)

Alex: I think with the example for CISSP is, or Aussies will know it as just CSP, I think the intention was good behind it, because the idea was similar to like being a chartered engineer or being a chartered something. Like, all being chartered says is that you have done extra training and reached a minimum requirement that is recognized throughout the world.

Where CSP I think fell down probably more recently is that it had good intentions to be that. But when the huge skill shortage in cyber was apparent and CSP was essentially like, you could look at any job ad out there and it was like, “Three to five years experience. Must have CSP.” and it just became this ticket to get a job. And so many people were just sitting exams and then when you’ve got that influx, like it doesn’t take much for that to crack.

And when you’ve got so many other people that may not have all those years’ experience and that base base level that was there initially, that drops that base level because then they can sign off on other people’s work.

And then they get into the industry, which is, yeah, I think still now, and this is probably a whole other topic, but when someone gets into the industry and they’re not potentially performing at standard, it’s easy enough for them because they’ve been in for a while to just move and keep moving. And it’s that whole they never want their performance managed, they just want to pass it on to someone else to like let them be someone else’s problem.

Si: Yeah. I remember a conversation I had with a police officer once who was talking about the then- — and I won’t state when this was, so we’re not going to identify any particular individuals — but the then-head of the Met Police who basically had gotten to the point of being the head of the Met Police because people kept promoting them to get rid of them from their unit. Nobody wanted them, nobody likes them. Nobody, you know, they weren’t competent. But the easiest way to get rid of someone is to promote them to the point that you don’t need them anymore and they get moved somewhere else.

Alex: It’s exactly like that captain from Brooklyn Nine-Nine, if you’ve watched that show where he is just in the right place at the right time all the time. And he is just an idiot and he keeps getting promoted and he is just like, “I don’t know how it keeps happening.”

Si: Yeah, yeah.

Alex: Like, thinking back to my time in the military, there’s definitely things like that. Because a lot of the military is time in position to then get promoted and people don’t want to deal with you. So you either get moved to a unit or to get you out they just promote you, which, it doesn’t happen all the time, but there are definitely people in positions that shouldn’t be in those positions and that’s just because they’re in long enough and they just get moved around and promoted up and which again, happens everywhere. Like, it’s not just a government thing. I think it’s just easier because it’s harder to get rid of people once they’re in a government job.

Si: I mean interesting. You said…

Alex: Slight off-topic.

Si: Well yes, slight digression. It’s good for us. It’s fine. We’ll sort it out in post.

Alex: We’ll sort it out in post.

Si: But, you know, you said chartered. And that’s an interesting thing. I’m actually a chartered, what in the UK, I’m a member of the British Computer Society. So a Royal Institute for computer professionals and I am chartered under that.

But that’s a generic computer type thing. Do you think we could get around this by saying, “Okay, well let’s have a proper Institute for incident response or a proper Institute for forensics” and then say, “Okay, we will make chartered membership properly assessed against, you know, skills and things.” Make that the gold standard instead?

Alex: Yeah. I definitely think so. And so I know, I don’t know what the computer science one is, but I have a friend that’s been through the engineering one and it is very in-depth. Like, it takes years to get chartered as an engineer. And then even then, like I said, you get chartered and all that means is you pass a base standard so that you could be an engineer anywhere in the world kind of thing.

So I have heard rumblings of, I guess like Engineers Australia kind of body talking about cyber, that was a while ago that they were looking potentially into it. I think again, where the problem falls down is that cyber is so broad.

Like, I consider myself a slightly above subpar incident responder, I guess. Like I did it for a while, I’m okay at it. But I would be terrible at GRC. And so if that base standard was just like, oh, you’re a base standard at doing this. Like, how do you then push it across all the disciplines that exist within I guess cyber?

Because when I think about the engineering one, she was chartered as a structural engineer, purely building bridges. Like, that’s what she was chartered as. And then like, I don’t know, much smarter people than I can maybe come up with a solution to that and you just become a chartered cyber specialist in an area. And then that’s what you’re chartered as, maybe? that could work.

Si: It’s interesting. Because I mean, I like the idea from an employer perspective and in fact I like the idea from a, let’s say legal perspective whereby I say, “Okay, I want an expert in a specific field to give evidence in court on this basis.”

And therefore for that, you know, it’s very unique, but actually as an employee, you know, I have been a forensic analyst, I do risk, I still do risk work. I like doing risk work actually. Like you I’m above subpar. You know, I’ve done that in a number of environments and that’s something I enjoy doing. Maintaining accreditation across both or making a career jump from one to another starts to become more challenging than it is now.

And I wonder if, and I’m a huge fan of the idea of taking knowledge from as many disparate fields as possible in order to progress any given field.

You know, I feel that, you know, as in certainly in terms of security, we should be looking at biology even to go as far as saying that, look, you know, we have evolution and these things have survived for years against direct predators. What can we learn in that regard of, you know, an attack defense mechanism that would allow us potentially, okay, yeah, we’re going to have to translate it, but is there something we can take from that?

And, to start really siloing people into, “Yeah, you’re a GRC professional. Congratulations. That’s it. There’s your accreditation to make a career jump. You’ve got to get another accreditation. You’ve got to get another certification.” Rather than saying, “Actually, you know what, you only come to this job and, and it’s like the CSP that you’re talking about. CISSP. I mean, the reason I have it is because it’s a base-level TV filter. If you don’t have it, people throw your CV away.

Well, you know, does it mean it’s, no, I mean, it’s just a thing to hold. Do I think it’s the pinnacle of it? Actually, the exam was reasonably challenging. There’s quite a lot of good information in there, so it’s a good standard in itself. But, you know, does it mean that somebody who doesn’t have it isn’t any good? No, absolutely not. Not in a second.

So yeah, did we talk about this last week? Your brain gets caught up. (We’re going to have to start another recording in a second, as well.) But there was a lot of debate about some geezer who published a paper, he’s a PhD student somewhere and it’s come up that some people responded and made comments on it. He’s like, “Well, you don’t have the right to critique my paper because you don’t have a PhD.”

Alex: I think you shared it through the week, that story. Yeah.

Si: Yeah. You know, there are so many people out there who don’t have qualifications, who don’t have this, who don’t have that, who are incredibly good at what they do. And I don’t know, it’s a difficult one, accreditation, and that is a really, really problematic area to look at.

Alex: Yeah. I think as the industry grows, chartership will become a thing. Quick opinion on certifications: I think if you are aiming for a job or have a job that needs a certification, then they’re great. But once you get to a level where you are getting on-the-job experience, I don’t think they’re necessarily needed unless it’s in an area that you want to learn about.

I think certifications are great because they distill so much knowledge that you could go out and find yourself. If it’s a good course, they distill so much and will deliver it to you in a way that’s easily digestible in a short amount of time. I think the value is in the course, not necessarily the certification.

And there are examples of that. Like, particularly when you look at courses that separate their exam cert and their course content as well, because sometimes maybe you’re just after that knowledge from that person running the course, because there are very smart people that like to make a living, they’ll sell their knowledge and it’s sold in a course format that you can go do.

And I think the courses that offer practical content, personally I rate those higher because I’m in a technical field and I like learning by doing something practical. Especially the courses that force you to learn.

So one of the really early certifications that I did was OSCP, so the Offensive Security Cyber Professional, which is a pen testing cert and like, I don’t do pen testing, like, I do incident response and digital forensics. I learned a lot about attackers because I learned a lot about myself and about humans doing that course.

Because when you read a lot of APT blogs that come out, they’re like, “Oh, these attackers, like, phish their way in. They like, hid themselves in these directories and then they crafted their own malware and they executed, and this is how they ran something on the network.”

And that’s great. Like, that’s APTs and high-end corranals. When I was looking in incident response for things and I was just like, “Oh, I’m just going to go check the local user app directory for them dropping tools.” And then finding tools and being like, “Oh, this is awesome. Like it’s a free find.”

Like, they didn’t use them, but I found some of their tool kit and some of their files, because that’s what I’d do. Like, when I was doing pen testing, I was super lazy and would just like not care about forensics and be like dropping tools everywhere.

And like the value in that course was learning the process, learning when people get lazy and then learning how to figure things out yourself and going back to that scientific method that you apply, you test something yourself and realize a lot of things other than just reading articles and blogs and that kind of thing.

So yeah, that’s where I find like, certifications that have that practical element where you’re actually hands-on, not just like, stepping through lab questions, but getting really into it. You actually learn a lot of skills that you probably don’t realize are the aim of the skills that you are meant to be learning.

Because you might run into like, even for example, like I used to run training where one of them was I’d give instructions and go, “Here’s this VM, you’ve got to run it. And then here’s your object of the lab.” Now the object of the lab was actually a broken VM and I wanted them to figure out how to fix it, but they had an end goal that wasn’t that. And so if they got stuck on that and then they’d constantly ask questions, you would quickly work out who was self-sufficient in trying to troubleshoot things.

Because there was no time gate on doing that. It was just, “Here, you’ve got this, you’ve got a week. If you really run into any troubles, like reach out, but otherwise just use Google and figure it out yourself.” And probably like 80% of the people would Google it.

It was a pretty easy fix to find on Stack Overflow, but you’d figure out the 20% of the people that were just like, ”Oh, I’m just here to just get through the course and just pass. I don’t care about learning anything else unless it’s directly tied to what I’m meant to be learning.” So that was like a good kind of icebreaker exercise to just figure out who were going to be the problem people in your class.

Si: Yeah. By accident I did something similar because I gave a piece of coursework out and there were two images involved in it. And I gave the hash values for both images and I gave one of them wrong.

And it was interesting because initially nobody checked the hash values and they were like, and then I started to get questions back of like, “You know, these hash values don’t match was, is this right?” And I was like, “Well, either I can stick my hand up and go, yeah, I cocked up or I can turn this into a learning exercise.” And I went, “Well, okay.”

Alex: Valuable teaching moment.

Si: Yeah, this is it. Teaching moment created by accident. You’ve got a hash value that doesn’t match. What are you going to do about it? What are the implications of it? What does that mean to the rest of your case? What, you know, and go from there.

Alex: You’ve probably got some people listening who are just like, “I knew it. I knew he stuffed it up and didn’t admit it. All these years I’ve been waiting.”

Si: Yeah. So yeah, you’re right. And it was interesting to see the people who came forward. I mean, I know students. You know, after the first couple have come forward and asked these questions, then they all go round in the back channels of, yeah, we need to accommodate this, we need to think about it.

But actually the ones who picked it up first and started asking questions clearly had been a bit more on the ball than the others. And it was quite fun. It was quite fun. So much so that actually we left it in the following year as a deliberate ploy.

Alex: I always love putting in stuff like that. Like if I ever run a CTF, like the first thing you always see in CTFs and this has caught me out before is here’s all your data and here are the hashes. And there’s been times when, and you tick the little thing you say, “Yes, I’ve checked the hashes.”

And there have been times where I haven’t checked it and I don’t think it was on purpose on the CTF, but the memory image that I had corrupted and I couldn’t get volatility profile to work. And I was trying for hours. And then my friend was just like, “Oh, you checked the hashes, right?” And I was like, “Oh no, I didn’t.” Checked it, and I was like, “Oh, damn it.”

So I like, redownloaded it, checked the hash and was correct. The second time I was like, “Oh, okay. This all works now.” So I just lost like four hours of the CTF to that. But it’s good. Like even then, like in CTFs it’s flagged, check the hashes before you even start.

And it taught me a very good lesson is: there’s never a time where I don’t check the hash now. Like, no matter what it is, like if I need to make sure it’s there, or I’m doing some CTF or some training, I’m always checking hashes. And it’s even flowed into when you see websites and you’re downloading third-party software, and it’s like, here is the hash once it’s compiled based on what we know.

Because you know there have been supply chain attacks where the GitHub repository is clean code. I forget who this was. I was reading the article the other day, but it was like clean coding the repository, so you could go through and do your own code review. But they’d got into the release page and inserted malicious binaries for the pack staff.

And I don’t think they changed the hashes. So if you check the hashes, then you would’ve noticed that the executable was different from the one you were meant to be downloading, or you could at least go back to the authors and go, “Hey, you haven’t updated your hash.” And they would’ve realized someone has put it in. Or you could’ve compiled it yourself. If you were that paranoid, you’d be like, “Okay, cool. I’ve done my own code review. Just compiled the execute on myself.”

But, you know, I think those like little troubleshooting lessons that you learn along the way stick with you the most, because you’ve struggled with them so much. And they’re like your failings that you remember. They’re really good. And I think that’s where practical courses really shine. Cause you always are troubleshooting things that aren’t in the course. And it’s usually your own hardware, like how we’ve learned how to close a Zoom share session today. like our plan, our goal was to make a podcast, but we learn.

Si: I say that, it’s a Mac, so Alt+F4 wouldn’t even work. But yeah, I think you’re right. It’s an interesting question because actually when you look at it, those are the sort of learning experiences that certification in and of itself tends not to get you.

Alex: It’s very in general, pristine. Like the environment, and cause if it’s not technical, then it’s just questions and you don’t get that opportunity. Or they spin up all the labs for you in general and you don’t get any of that troubleshooting experience.

Si: Yeah. So I think that’s where classroom-based training in a broader sense is a better bet because especially if you have practitioners teaching who, you know, will tell you the gotchas and the issues that you’re likely to face. But again, you know, real-world experience is the king of everything.

And, you know, it’s on-the-job training therefore, and where we started this conversation in the, “Okay, let’s pull somebody in, let’s give them, you know, a certain amount of training, but let’s give them a good mentor. Let’s give them, you know, ongoing, continuing professional development.” God, what a horrible phrase. CPD. So we’ll give them CPD.

Alex: Everything’s acronymed.

Si: Yeah. Thank God for that. Too many TLAs.

Alex: I think coming full circle around to that, though, as well is where the cyber academy, and it’ll be really interesting to see over the next three years, the quality of talent that’s coming out and even with other Big Four companies that are doing the same thing is where they might fall down is that mentorship or, because being a good practitioner does not make you a good teacher.

And that’s true, as well. So people who generally teach courses are good at teaching, even if they’re not up to the current standard of industry standards. And it’s two separate skill sets there that I would say, like, they don’t even kind of coincide, like you need to develop it’s kind of like, you could be really good technically, but a terrible manager, because it’s a separate skill set. It’s like a soft skill set that you handle people and teaching is the same.

And so I think where it will fall down or where you won’t get as good bang for buck in learning is if you don’t have good teachers and especially if you have a bad experience with that, because if you have one bad experience, that sticks with you for a long time. So if you have a bad mentor for like one or two years, that’s really going to leave an impact on your impression of the industry as a whole.

Si: Yes. Yeah.

Alex: So I think that as long as the caution’s taken in that area, that they realize that they need to give the technical practitioners training in order to train people, then it will work really well.

Si: Yeah. Yes. It’s very, very easy. And I hope I haven’t done this and, you know, I’d stand up and talk in front of students often enough. But it’s quite easy to make someone hate a subject. I mean, God knows plenty of teachers did it to me while I was at school.

And also it’s an interesting one. It’s just like you can just have a personality clash. It’s not necessarily that somebody is good or bad. It’s just that, you know, there are people who you won’t get on with and, you know, you’ve got to accept that in the real world, but when it comes down to going and listening to lectures, there will be people who you like listening to, there’ll be people who you don’t.

Alex: I think the benefit at university though is you generally have your lecturer and this could be different for the way you teach your classes and how the university runs, but you generally have like your head lecturer who lectures to all the students, but then when you’re doing your tute work, you have kind of like postgraduate students or master students that are running those tutes that have done the course before.

Si: That was the way I learnt. And that’s when I went to university and unfortunately my math tutor and, I mean, it wasn’t that he was bad, in fact, I really liked the guy, he was great, he was lovely. I just didn’t understand a bloody word he said. So, you know, I mean, he was really bright, he just couldn’t drop his level to where I was. And trust me, at maths I’m quite a long way down.

But he couldn’t do that. He couldn’t come down to explain something to somebody who was struggling. And for me that was a problem. Like I say, a lovely guy, you know, went out to the pub with him, we talked, we had conversations elsewhere, but in that regard he was a lousy tutor.

But no, in our course, actually we embed everything. So I was teaching and tutoring, we were, doing labs together. I had a, I don’t want to call him a teaching assistant, poor Gav, if he is listening to this: Gavin, hi, cool. You know, and he worked with me to go around and make sure that students were coping in class and doing that problem solving thing.

They didn’t have separate tutorials in my subjects outside of what we did. They did in maths, I believe. But then, you know, that is maths. It just needs more. It’s mathematics. It needs more work than other subjects, I feel.

Alex: Yeah. Same with my experience. Like, maths and engineering, you had separate tutors for each subject as well.

Si: But one thing that my university, you know, was doing was very much focusing on the fact that we would have practitioners come to teach subjects. People who had been there and done that in the industry. So I went and I taught things.

Certainly, I always found it more exciting to hear people who were really doing a job than people who had, and sorry, again, no offense intended to any people who are career academics, but it’s like driving.

I was thinking of this analogy earlier, actually. Certification is like driving: you get in the car, you learn to drive, you follow all the things, you sit your test, and then you learn how to drive and you meet all of the idiots on the road that you hadn’t come across before. And you find out all of the stupid ways in which in this country at least road surfaces go wrong, people disobey rules, you know, and the reactions and the way that people actually work.

In theory, theory and practice are the same; in practice, they aren’t. So, you know, it is one thing to teach and another thing to do. And again, you know, it is one of those wonderful things. I mean, I remember doing, I’ve taught operating systems, I did computer science at university.

Computers are deterministic. You put the same input in, you should get the same input out. Does it work like that? Hell does it. You know, you can give a computer the same input and you can get 15 different results out of it. And it will take you years to figure out why.

And that is the reality of it is they are so complex, so advanced, so much, and, you know, like a Windows is however many millions of lines of code that is now Linux the same. You know, one typo, somewhere embedded in all of that will cause something to go in a way that you haven’t anticipated.

And it would compile and there would be no errors and, you know, and yet still that logical error or that programming error will prop up one time in 50 and cause something to happen that you had no idea about.

Alex: I think like, so thinking about universities and the PhD structure, like, it’s probably built into the industry, though. Like, there are roles out there that are pure threat research roles, or like just thinking about the big EDR vendors out there and big consultancies, and even Microsoft has like threat research or pure research roles where the body of work that someone would do there would be equivalent to a PhD.

And the idea is even if it’s not directly practical now in what they’re looking at, at least the research is there for use for later on. And I think that’s the big thing with PhDs is even if someone studies something novel that hasn’t been studied before, the use may not be apparent now, but as long as someone somewhere in the future does get some use out of it, and I’m sure like there are plenty of PhDs that never get referenced again, or they get referenced as here’s an example of something not to do in future studies.

But it may not be apparent for 50 years where someone’s just like, “Oh, like this thing that this person did back then at some weird university is actually really useful in this application that didn’t even exist 50 years ago.” So yeah.

And it has its time in its place and people who are interested in it. Like, I don’t think I could go back to full-time study or even part-time study. It does my head in .

Si: I would love the opportunity to do it, it just doesn’t pay the bills, which is a huge shame. But yeah, you’re right. I mean, and that’s why your initial reading if you’re doing a PhD is so important is that you go out and find all of that prior research and figure out what’s good there and what’s not.

Just as a point of interest, and you’ll find, for viewers and listeners you’ll find these talks on Forensic Focus somewhere. But there was a DFRWS Europe was held in Oxford earlier this year. Was it this year or last year? Earlier this year, I think yeah, it was this year back in March. It was cold and it just seems like such a distant memory.

And there were some very interesting talks about research that people were doing there on forensics. One of which was they built simulation homes and then set fire to them to find out what happened to the IoT devices and how they degraded as a building burnt down, which I thought was absolutely fascinating.

And it was just like, you know, where do I sign up to get the job of lead arsonist in the university department? It just sounded brilliant.

So yeah, and, you know, at some point, and it was interesting, because actually you could tell from where the IoT devices were found and the way that they went offline and degraded is actually where the fire started from. You were able to track back to a source of, you know, an incendiary thing.

I thoroughly recommend listening to it. It was a very, very good talk. It wasn’t a particularly long one, but you’ll find it on Forensic Focus somewhere and be able to have a look back for it. In fact, I’ll dig it out, send it as a link and then Christa will have it.

Alex: We can put it in a link in the show notes for this one. And for our Australian listeners, and we’ll chuck this in the show notes as well, the DFRWS conference here in the APAC region is on September 28-30 in Adelaide. So my hometown, which will be cool. I won’t have to travel anywhere to go to that one.

Si: Are you going to go?

Alex: Yeah, for sure. Yeah.

Si: Excellent.

Alex: So, the company that I’m part of now, we are part of the Australian Cyber Collaboration Centre. So the ACCC here in Adelaide, which is doing some really good work with trying to bring together different industries together in a cyber hub. And so located at Lot 14, which is like the old women’s and children’s hospital, like back in the day. And there also used to be a vet hospital here, as well.

So they’re like refurbishing all the buildings and stuff, but the topic for another day is that actually MITA has created their first ever innovation hub outside of the US in Adelaide in Lot 14, which is really, really exciting. So they’re looking to leverage I guess Adelaide and the companies down here in a lot of their research with the government and with our company and other companies as well.

So yeah, I guess once that kicks off, they should be moving in officially into their office in January, February next year. So that’ll be really cool once a lot of the research projects kick off and there’ll probably be lots to talk about around that space.

Si: Ah, really exciting. No, good stuff. And also gives me a good excuse to come to Adelaide. So that’s fine.

Alex: Definitely, definitely. Come around Fringe because anything good to do in Adelaide it’s around Fringe when all the shows are on and then the rest of the year, you can only drink wine. That’s that’s all that’s happening. So, I mean, it depends how much wine you want to drink, but you can also drink wine at Fringe.

Si: Yeah. So, you know, you can do both.

Alex: Both at the same time. Perfect timing, aim for March: slightly good weather, lots of wine, Fringe is on, MITA will be open, lots of things happening.

Si: Okay, March next year. I’ll see what I can do. That would be brilliant. All right. Okay. So, now, I’ll try again, because I didn’t bring it up to remember Christa’s out, which is, thank you very much everybody for coming and listening. This was the Forensic Focus Podcast, Alex and myself. And it’s been lovely chatting with you, I’ve really enjoyed it.

Alex: Yeah, you too. It’s been good. It’s good that we planned a topic more than five minutes beforehand.

Si: Yeah, no it is definitely. Although the recording next time. So, next time we’ll have a topic, a long-term recording and we’ll get it right from the beginning on. But you will be able to find recordings and transcripts of this on the Forensic Focus Podcast page on forensicfocus.com. And also you will be able to find this on Spotify, which to this day I’m still stunned about because I listen to podcasts on Spotify and I never thought I would be there.

Alex: And we’re on Apple Podcasts, as well.

Si: Are we? Blimey. Worldwide distribution. So anyway, fantastic Alex. Thank you very much. You take care and I’ll talk to you with Christa in a couple of weeks time. Have you seen her new study by the way?

Alex: No, I haven’t.

Si: She tweeted it and she’s got a whole setup now for doing these recordings.

Alex: I don’t think I’ve got her on Twitter. I’ll have to have a look.

Si: Yeah, go dig it out. It’s a lovely shade of purple. and I’m going to have to step up my game and stop blurring my background.

Alex: I’m waiting until I move. When I move, I’m going to deck out my office. It’ll be great.

Si: Nice. All right. You take care.

Alex: I’ll catch you later, mate.

Si: I’ll talk to you later.