Matt: And good morning, everyone. So yeah, like Melissa said, today we’re going to talk a little bit about screen time for iOS and digital wellbeing for Android. A little on what they are and how you can apply them to your investigations, why they’re relevant. So, like Melissa said, you know, our phones are absolutely tracking everything that we do. It seems like it’s just more and more as the technology increases and gets more advanced, but it’s something that can be good for us in the forensic community.

So if you have an investigation where, you know, you need to prove device usage or lack thereof, this is a place you’re going to want to go and be familiar with. So some of the tools are parsing this now. But even then, you’re still going to want to dive down into these databases a little bit deeper so you can get a good idea of what’s going on in the device as far as, you know, if the screen was on or off, or what app was in the foreground or, you know, when they specifically moved it to the background.

So it’s designed… both of these are really designed for the user, right? To be more aware of their device usage and even have some sort of control over it, you know? And, oh, I only want to be on my phone for five hours a day, but the cool part about that is that it’s logging everything. So for us, again, it pays off in dividends. Whether it’s a vehicle case or any other kind of thing where you’re trying to prove if someone, or find out if someone, was on their phone.

So with that we’re going to start with Ronen Engler. Who’s going to talk about screen time for iOS. So I’m going to turn it over to Ronen.

Ronen: Hey, thanks, Matt. Hi everybody. Thanks for joining. I’m going to share my screen in a few minutes, but I’m going to start by talking a little bit about the screen time. So Apple introduced it in iOS 12, and as Matt said that the idea came to help you understand how you’re utilizing the screens. So basically across multiple devices, so your iPhone, your iPad, and you can actually tell what you’re doing on the device, how much time you’re spending on it.

And since then they took it to a different level, where they show you better statistics. They try to aggregate the data to show you some stuff. I’m going to show some examples and explain how we can show you that information. I think Matt mentioned it. We can see actually under the hood and we can understand better things on the app level, and other things that are going on, and not just what Apple’s showing you on the mobile device itself.

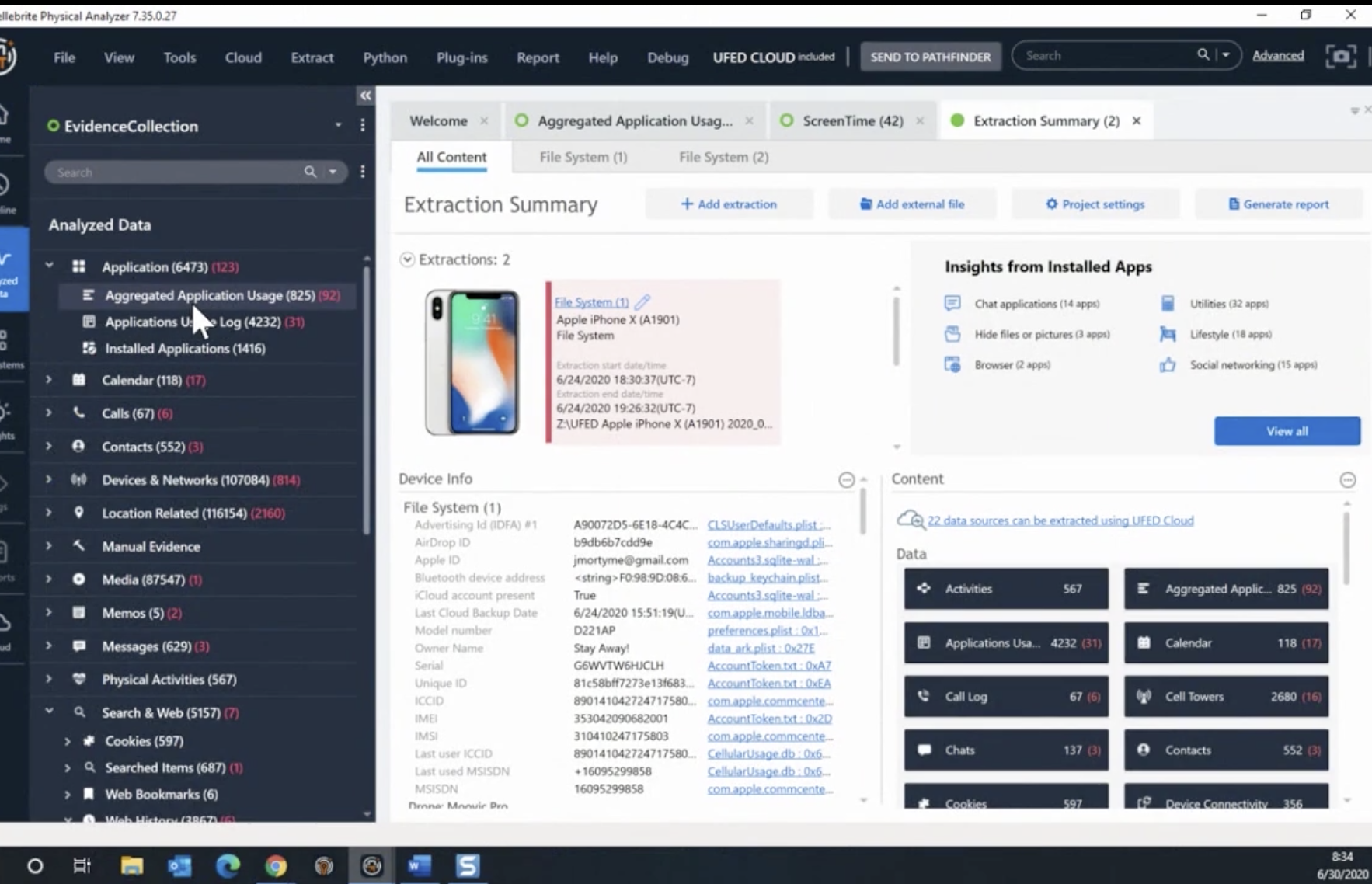

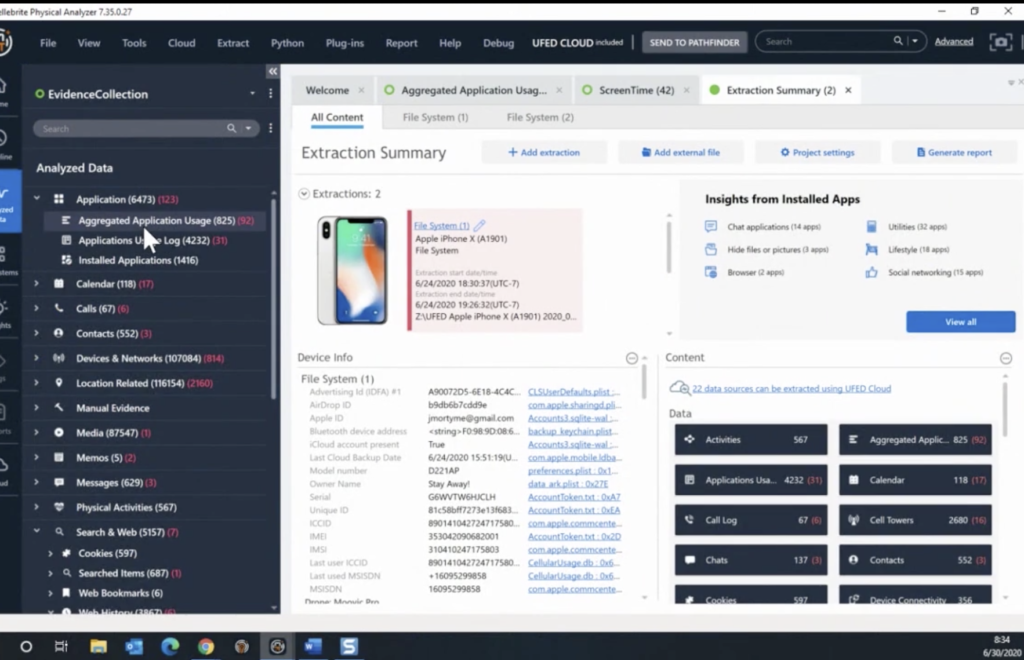

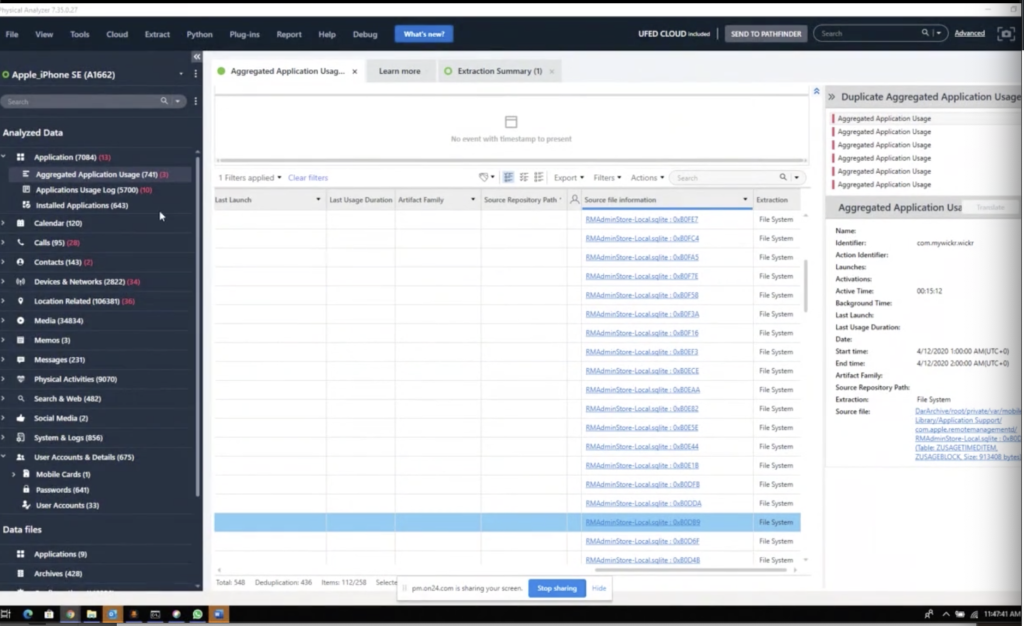

So let me start by trying to share my screen. Hopefully it’s coming up a few seconds. So I have an extraction ideas on a test device here. Hopefully you can see the summary screen. And we get the data is being analyzed into a couple of different places. The first place is that I’m going to talk about is the under application analyzed data application and aggregated the application usage. So when you go there you can see multiple entries. Some of them are coming from other sources, however, some of them are coming from… and I’ll scroll to the right.

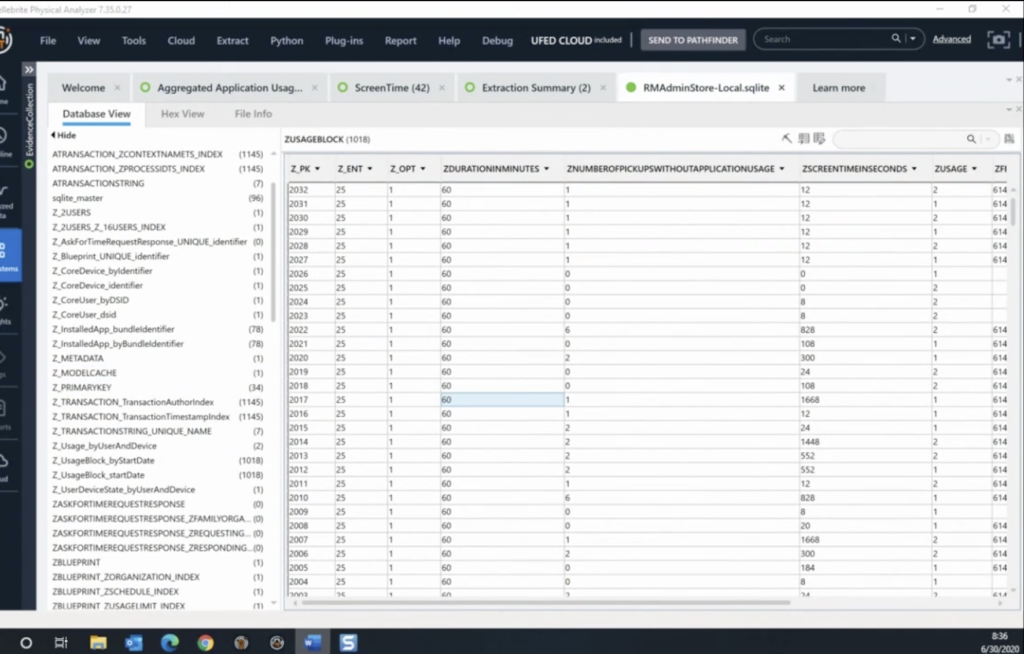

You could actually see the source, and it’s coming from the admin store here. And you can see that database includes data, but the identifier, which is the app that we’re using, the active time, so how long you’ve been active on that specific app, and something interesting here is that you can see there, the start and end time. The reason, yeah, because of the data that is being stored, doesn’t tell us exactly when it was used, but it gives us like a timeframe.

Let’s open up the database so we can see better what that thing looks like inside. So that database has a lot of tables with a lot of informations. Hopefully you can see that and it’s not too small. You can enlarge your screen. By the way, that function, in order to be available, the user needs to enable that in the settings. So you need to, whoever’s using that phone needs to turn on the screen time under the settings.

We did a lot of… I think Felix from the R&D did a lot of work researching that. And I’ll post his log in a few minutes so you can read the rest of it. A lot of cross-referencing the data between the different tables that we have. We do see a lot of applications and their usage can show you that there are multiple tables, including the information about the device information about the user. So that is something that is actually interesting. I only have one line here on that table because there was only one user.

However, with the screen time, you can not just track your own data, but you can connect it to your family. So if you have family members that are using their devices and you can see their data, or if you’re a parent and you have your kids, then you will actually get their information in here as well. So things that you can see in here will include the apps that they have installed and they’re running on their devices and how they’re using it. And could be a nice, interesting source to be able to see where people are storing what they’re doing.

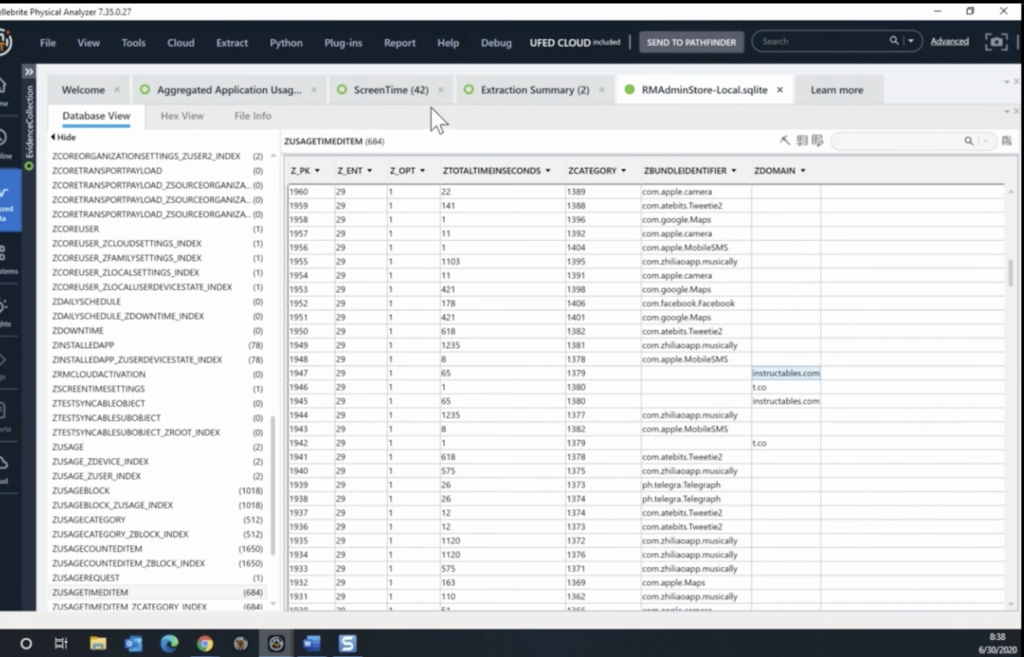

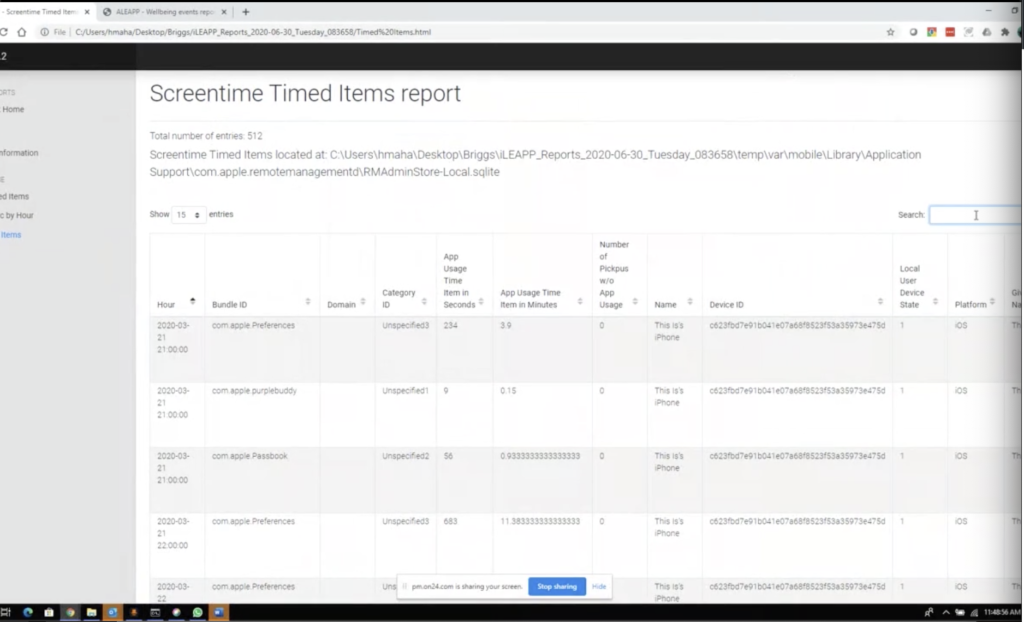

And since we have other functions that includes digging into carving deleted data from databases, we can actually find apps that were uninstalled from someone else’s device. So it’s something really interesting that you can see. If I go into… let’s see, see usage, timed items. We can see here that we have the blocks times for milliseconds, and we can see the list of apps that are being used. I hope you can see there as a one column says the Z domain, that actually is something interesting that we found, that they may store some domain names. So if you’re browsing your web browser, you might go to some website, well, it’s not tracking the website itself, but just the domain.

So if you go into the analyzed data, I’ll expand that, scroll down under the search and web history, we added a category called Screentime. You can see different domains that were used to browse on that specific device. So there are multiple things that we can recover from these databases. And hopefully this is something that can help an investigation, can see where, when things happen, and there are a lot of timeframes.

And with that, I think we’re going to answer questions towards the end, but Paul, I’m going to hand it to you to start talking about the Android part of it, which is somewhat parallel.

Paul: Awesome. Thanks Ronen. I think that was very informative, and I think there’s a huge part, and a huge kind of learning curve as part of this, to understand how else to kind of start looking at investigation and looking at artifacts that are more than just, you know, your regular browsing history. Beause like, even from my own personal experience, doing child exploitation investigations, how damning can it be to be able to show like, you know, he spent X amount of time on this website, which is very well known for hosting childhood child abuse materials. I mean, like that stuff, it’s very powerful and it’s stuff that’s again, as digital forensics kind of as a whole, like the digital intelligence piece, that there’s so much to this, that there’s, we need to kind of keep adding to it. And keep looking at past those additional or those initial artifacts.

So as Ronen said, I’m going to cover off the the Android piece. So Android digital wellbeing, it’s something that’s very similar to iOS screen time. The only difference is that it’s fairly new. So what we have seen that it’s going to start being introduced in Android 10, so we haven’t really seen it too much. We do have a special guest that is here in the background, Barack, which is part of our R&D team as well, that did a lot of work on this. And it’s kind of helpful, made our job a lot easier to kind of display all this. So ask questions about this because I mean, it’s something new to all of us. He’s got some there’s some some great level of detail that we can obtain from that.

So again, so digital wellbeing is very similar to screen time and almost to the equivalent of a knowledge C as part of as the iOS. It’s not quite as in depth as the knowledge C database on the iOS, but definitely can help you provide information to aspects of application usage, which devices, or which applications are in the foreground, the background. So again, it’s not to the same level as the iOS piece, but I mean, it’s definitely something that can help determine or provide you more information about this.

So again, so to start off, it started to get introduced to the Android 10 as a whole. So that’s why we probably haven’t really seen a whole lot of it. We haven’t heard much about it. The other piece as well is that it has been around on Google Pixels since Android nine. So luckily enough, we do have Josh Hickman’s image loaded. So I’m just going to share my screen quickly and I’ll show what we are going to be showing.

So in Android it is a little different. So I have Josh’s Google Pixel loaded here. So again, this image is readily available to everyone. We do have a link of it at the end, so everyone is going to be able to have this, download this, take a look at it, poke through you know, look through it, validate it. So the main locations that you’re going to be looking for of course, if you want to do the manual parsing of it is under your data folder, and then com google.android applications, wellbeing database.

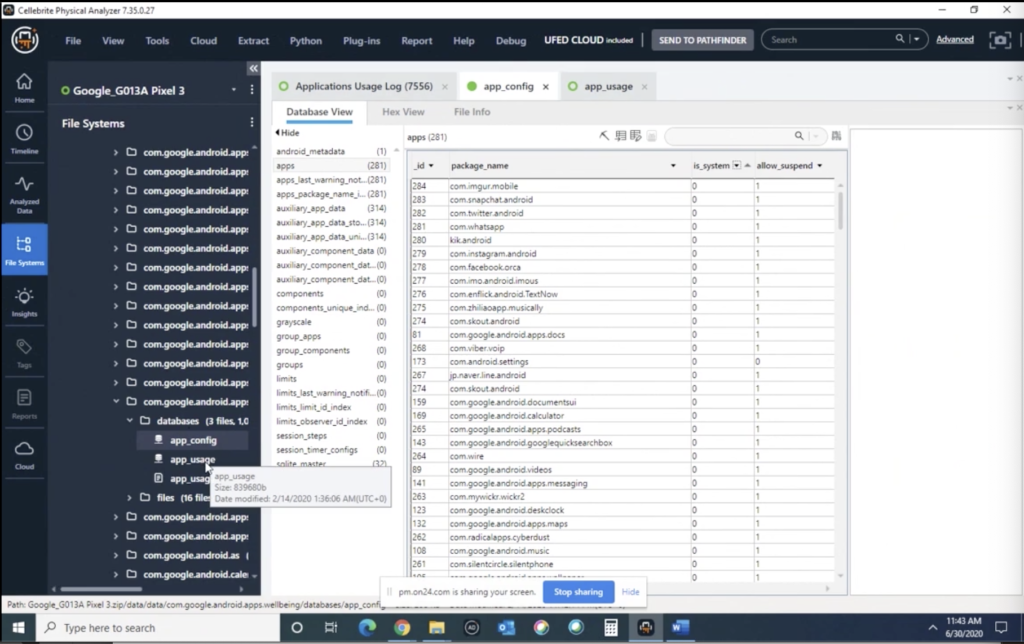

So here at the bottom, you can actually see what this is. This in here, as you can see, there’s two primary databases that are of relevance, of interest: your app configuration ones and app usage. So the interesting piece, as well, is the app configuration one shows all the applications that are installed on a device. So not only just as a whole, whether or not which applications they are, but actually lists which ones are system ones or which ones are user ones.

So as you can see here, if you just kind of order it by whether it’s zero, so the entry zero, it’s showing that, you know, Kik messenger or Snapchat, Android all these ones here are non-system ones. So user installments. So you’re texts now. And again it’s more artifacts to kind of help show which applications are installed on it.

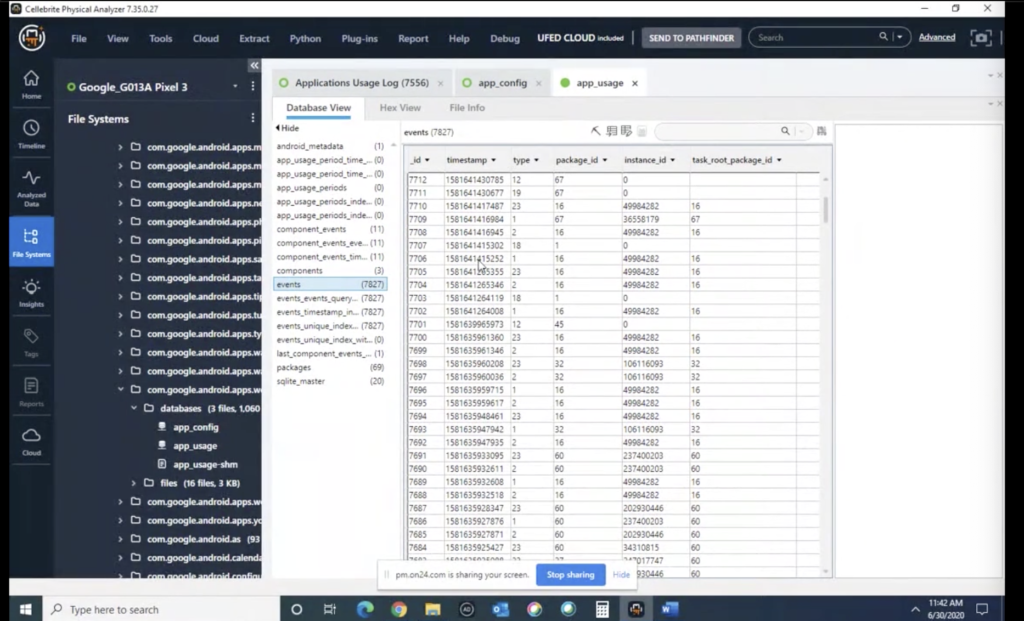

So application usage, the apps usage database is… that’s where we also pull some of that information from. So of course it’s stored in a database, or database structure, and there’s various events. And again, I’m not quite sure exactly how far we’re this stuff can go back, but the whole premise of these databases, these types of information that is stored on the phone, is to help the end user, to kind of help, you know, not like, technology control them.

I remember there’s this little video on Android or on the Google Android site that actually talks about, mentions, it asks people, you know, is technology controlling you, or are you controlling technology? Because this is kind of that mechanism to help people realize how much time they’re spending and how it’s affecting their life. But also it creates great artifacts for examiners to be able to show that you know, these types of events, it lists all the type of events that are taking place on a device, which is great for us and examiners as a whole to be able to kind of look at this.

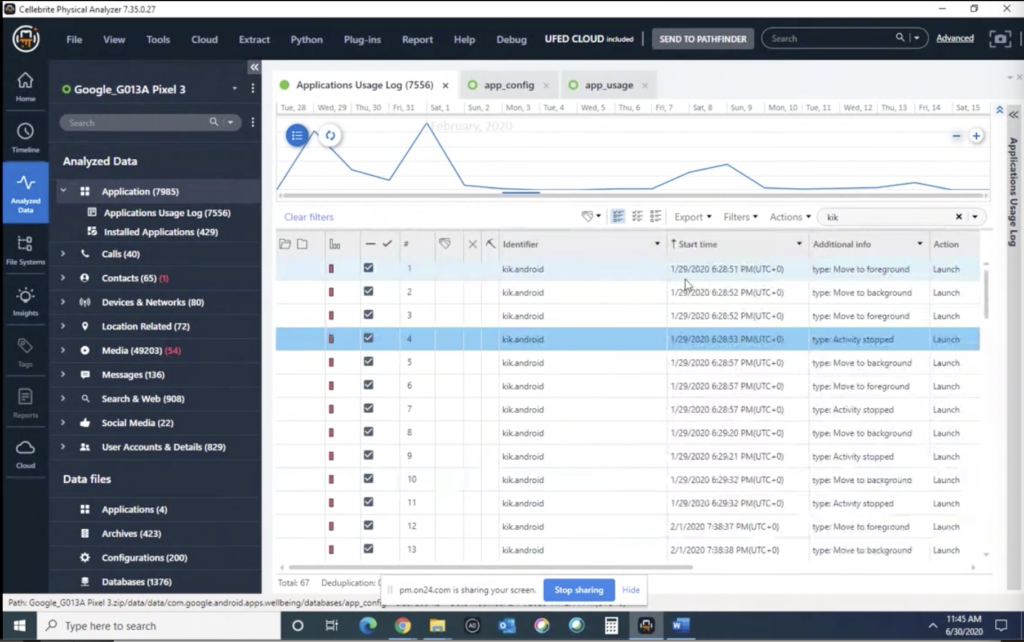

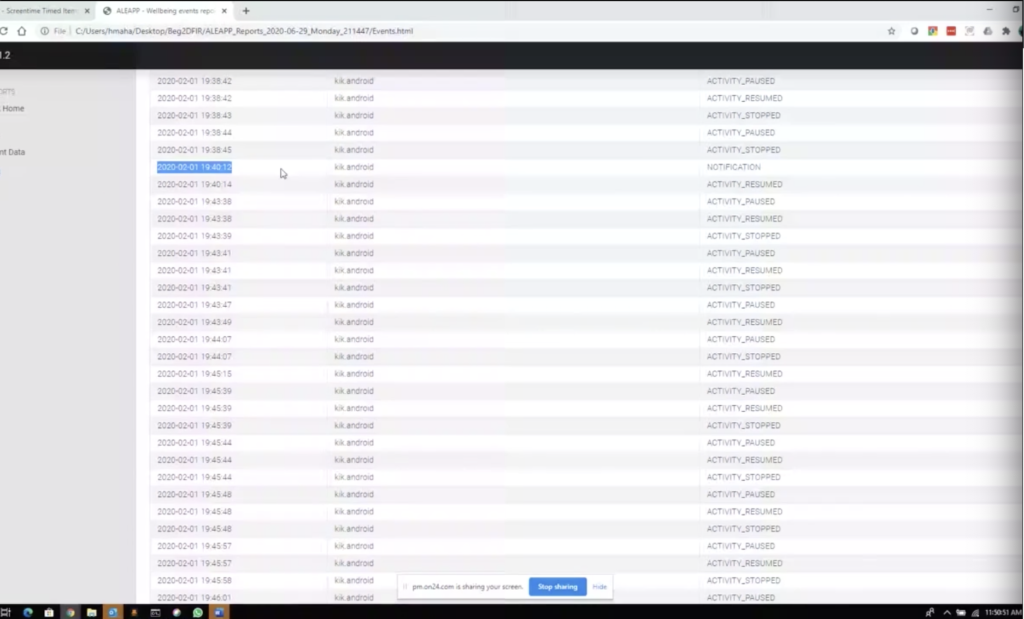

So of course, all these pieces are all part of the Dakota data that we are looking through, that we are providing. And under analyzed data, under applications and application usage log, all that information is parsed here. So things like your interruptions, your notification interruptions, there’s various… activity stopped, activity started, I think I haven’t sorted here. What are, you can even just, you know, if you want to look up Kik, how many times was Kik used, and then kind of the activities back and forth.

So, I mean, it makes it very easy, very, very easy to be able to kind of to show, well, this is how often and how frequently this is used. So again, the whole point of it is to show the end user of how much time they’re spending on this. But in the end as a forensic examiner, this can be a wealth of knowledge to kind of show how much the actual usage of it. Andit defeat some of those alibis that are people saying that, you know, I’ve never used this, I just downloaded it.

Well, you know, over X amount of time, you’ve interacted with Kik 67 times, which they, you know, they might’ve never even noticed that this there’s so much stuff that’s happening in the background. So again, it’s just to kind of add parts to your examinations, additional stuff to look at. Of course we do this for you. This stuff is always in research as well, so there’s more parts to it. I’m going to stop sharing my screen. Heather’s going to take over and she’s going to kind of talk about what else we can do as part of that.

Heather: Thank you, Paul. I have one slide before I kind of go live and show you some things. So validation, that’s something that I always preach about. Talk about. It definitely matters. So I’m going to show you ways that I like to validate both Android wellbeing and iOS screen time.

The first thing I usually do is, I will start in PA and I’ll search through the results and I will just filter it down to what I expect is going on. And then I follow the source, which I saw some people were asking in the chat about the file path. So I’ll show you what that looks like. And then I just let that drive me through my investigation. So I’m going to share my screen and I want to show all of you a few things here.

So as soon as this pops up. Here, I have Josh’s Checkm8 extraction loaded, and hang on, I have to go click share. That would actually be helpful. I’m going to show you Josh’s checkm8 extraction. Paul was just showing his Android extraction. And so I’m going to go a little bit back and forth but I just want to kind of show you my methodologies on what things will look like. So my screen should be coming up here in a moment and you’ll see that I have inside physical analyzer.

I did exactly what Ronen had done and I sorted by the source file. So I’m at the RMA, or RM admin store. I always want to call it RMA. And this is the screen time. And then when you find something of interest, so let’s say Wickr is of interest and you want to validate, is it correct? Is the tool getting everything? I will often, as Ronen and Paul both did, go to the database and take a look around.

So let’s say you go to the database, which they’ve already done. And you’re like, now what? So this is where I’m going to turn to Alexis’s tools. So I created a directory called Briggs on my desktop where I have iLEAPP and aLEAPP. So the first one I’m going to run is iLEAPP. And I’m just going to, I ran it last night and this morning to make it faster. So it’s ready and processed, since we have a short period of time. But what I did here is, I de-selected everything. And I was very specific on what I wanted to get. So instead of waiting for it to parse everything, which it’s pretty quick to begin with, I went down and I said, just screen time. I pointed it to my tar archive and parsed it. And I’ll show you what that looks like. And then I did the exact same thing with aLEAPP.

So for iLEAPP, if we care about Wickr, I can just search for… and spell it right would be helpful. I can search for Wickr in the top right? It’s going to show me over here. You can do generic by all counted items, timed items, and then also make sure you’re showing all your entries. I usually change this to all so you can actually see, and then you can actually add up all the time that physical analyzer had shown you. And it should be about the 15 minutes or whatever. I’m terrible at simple math. So I’m not going to do that live on a webinar for you, but let’s say you wanted to do the exact same thing. Paul, you were just talking about Kik, I believe. Right?

So if I go out and I change directories into aLEAPP–

Matt: Hi there, before you continue, Alex Briggs, he’s actually on here, actually made a great suggestion through the chat that he messaged. He’s like, for Android, this data is also complimented by usage stats, the XML and the [indecipherable] that create a more rounded picture for user activity. So again, great comments about, you know, not just solely looking at one piece but looking at it as a whole, as part of the other parts as well. So thanks.

Heather: That’s the final thing that I will tie in as well, because I like to put it all together, but if you just quickly need some data, so here, same thing in aLEAPP, you can do the same thing you can do in iLEAPP, you can say just these artifacts, parse it, point it to the directory and it will do the same thing. And typically I run everything because I want all the pieces put together and I think it does make it helpful. And then when I switched to aLEAPP, you could do the same thing. So you talked about Kik, Paul? Let’s do Kik.

And then again, I have it sorted by 100 entries and you can see what actually occurred. Did the person get a notification? So maybe the person was driving and got into a fatal car accident at this point. And you could say, well it was just a notification that popped up, did the user actually resume activity? Did it come to the foreground, the background? So you can put all these things together and to tie in what Alexis was just saying, if you found something of interest, this is where I would, honestly, when you’re in these files, I would hop to the timeline and I would go and say, okay, what happened right before? What happened right after? Put all the pieces together, because it’s the only way you’re really going to get the truth.

But I love using other tools to validate your tool of interest. And I don’t care if you’re using commercial tools or AXIOM, Oxygen, something else, but I rely on iLEAPP and aLEAPP mostly for my validation of these artifacts. And they’re fantastic. And thank you to Yogesh and Alexis for sharing, or helping last night when I had issues installing! So if you have installing issues as well, please feel free to reach out to them because fantastic support.

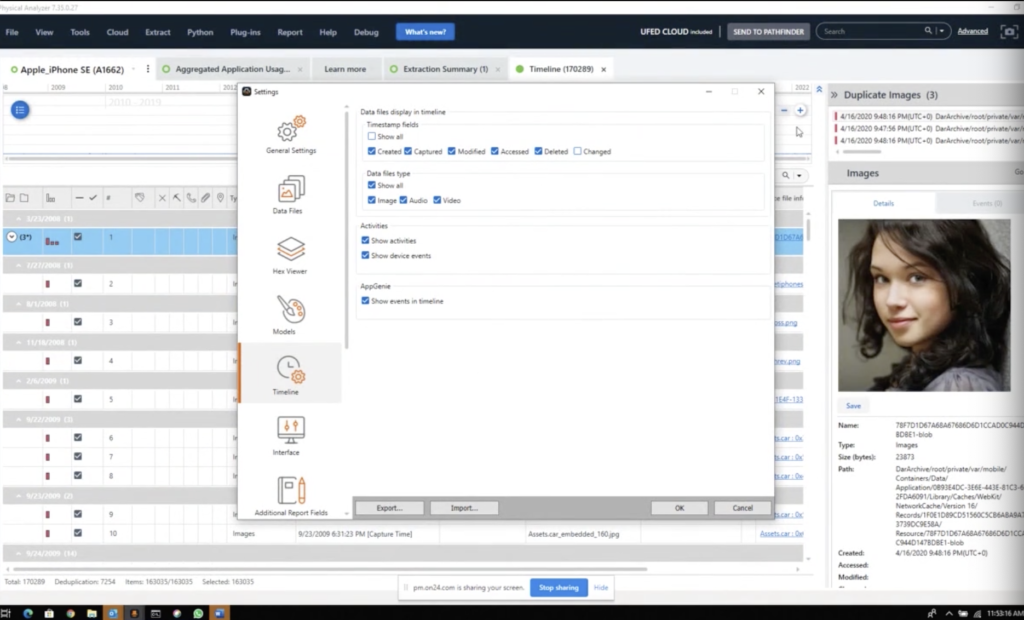

Matt: Heather, just in between. I want to address one other question. In PA, if you’re not seeing the activities and device usage in the timeline there’s a setting, and in settings under the timeline, if you click on timeline, there’s show activities and show device events. So if you’re not seeing them in there, when you think you should, make sure that’s turned on and that should help you out.

Heather: Yeah. Well, if there’s any questions, feel free to answer those. I’ll bring up my screen again to show that. Good point, Matt.

Ronen: So in the meantime maybe just to mention, but a few differences between the iOS and the Android. So the iOS has the screen time while the Android has the wellbeing. With the iOS, we see reports to the level of what features are being used, and with the Android is just the level of the app that is being used. So for example, if you turn on the flashlight, with the iOS you will see the flashlight was turned on versus with the Android, you would see that the camera was being used. Thanks to Barack for that insight.

Heather: The settings should pop there. So you can see what Matt was just talking about and how I got to this was right here in timeline settings, when you switch to the timeline icon. So there are a few blogs, they’re listed here. The first one is a look at Apple screen time feature and what it lends to forensics and that’s by Barack. And he is here answering your questions as well. It will tell you the file pass. It will show you the databases, the tables of interests. So make sure you read that.

The second one is by me, and I did just screen time and why it matters, how to validate, things like that. And then the final one there is from Felix, and it’s about digital wellbeing and the full path to it, the tables of interests, all the things you need to know to make sure that you’re validating correctly.

Something else I always do in Alexis’ tool — and I don’t know if I should say Alexis and Yogesh, whatever, iLEAPP, aLEAPP, the free tool — is you can go out to the scripts and you can always look inside to see what it’s actually trying to parse, which is helpful. So you know exactly what it’s getting in which pieces you have to put together.

Are there any questions? Anything else you need to see? Or has anyone actually used this in an investigation where it made a major difference? I know a lot of it is accident reconstruction or even, I know this sounds crazy, but there was a homicide that I was assisting with and Barack, you and Felix, I was in Israel at the time, and they needed to know if a message was synced from somewhere else or if the person actually sent it, because it made a difference if it was possibly a murder suicide, or a triple homicide, which they were leaning toward.

It’s nice and quiet.

Paul: It is. Heather, I know that we’ve shared in the past iLEAPP and aLEAPP, the tools as well, the links to them as well. Josh’s image. I realized that we don’t have them in the slides here, but we did have them in the past. So, I mean maybe provide that to the people that are using it, or that would like to take a look at that to see if they want to use their own little controlled tests, or where to grab aLEAPP and iLEAPP from from Briggs’ tool chest.

HEather Yeah. If you go out to, and I don’t know if I can put it in the chat or not, but if you go out to Github and you look up A Brigoni, you’ll find it. If you Google Alexis, you’ll find it. If you’re on Twitter, he actually tweeted it last night as well. Matt, do you know the best way to push this to the slides?

But you can also Google aLEAPP and iLEAPP, and there’s two PS at the end of each, and that’s an easy way to find it. Okay.

Matt: I had to mute myself. I’m going to put up the link to Alexis’ Github right now and I’ll push it out.

Heather: Thank you. Fernando, I agree. I feel like there are so many investigations where this could have helped. I know you’re on here as well, so Josh, thank you for your images as always.

Paul: I think this kind of speaks to kind of the forensics as a whole, as well kind of view evolution, the community, teaching itself, each other about these artifacts that it’s unrealistic, that any one vendor, one company knows everything because it’s not possible. Like, let’s be real here, with the amount of stuff that’s changing constantly. All these things that are coming across. I think it’s just more and more that you know, we’re going to learn about this as well.

Heather: And I know I’m speaking here for Alexis, but if you find something that is not parsed or a file of interest, if you reach out, Alexis and Yogesh are fantastic at responding, but this is one of the things that you in DFIR can also contribute back by pointing out things that could possibly be missed. And also don’t feel bad if you think you found a bug, yesterday, when I reached out, I was 100% sure it was me and how I was installing it. And it actually was, I was installing too many things, just ask. The support is amazing.

So as far as you not seeing the Q&A, I don’t think that you get to see it, it comes into us and then we just read them to you.

Matt Right. But I pushed some things out to the Q&A for them. So they have a place to submit their questions and it should get pushed out there. So there should be a tab for Q&A on the screen. And I know we have a different view than they do. A couple things came in from Alexis as well. And then it looks like one case usage from Sam. If you want to look at that, Heather.

Heather: Yeah. I just see that. So thank you for this feedback. It’s saying the application usage information was important in a recent homicide investigation, as it showed when the suspect was using a GPS tracking application and we were able to determine when he was following the victim from that. That’s awesome.

And this is from Josh. Oh, sorry, go ahead.

Matt: No, I was just going to read Josh’s thing. So Google mobile services contract requires OEMs to have a digital wellbeing solution, and they’re required to keep at least one week worth of data if they opt to implement their own solution, which is what Samsung did. So, fantastic information. Thank you, Josh. But also something to think about, you know, you potentially only have one week of of data there. So, you know, time is of the essence.

Heather: And I see Alexis made a comment as well. Josh did write a blog on that. So if you Google Josh Hickman, the… are you binaryforay, Josh, I think? Binaryhick? Yeah, the binary hick. If you go to that, you’ll find all of his blogs as well, another good person to follow.

And if you have ideas on things, you want us to talk about, email ibegtodfir@celebrate.com and we will consider your ideas.

Matt: Yeah. And so I’m talking to someone on the side and they didn’t get any of the Q&A links that I pushed. So I’m going to put them all into one chat, or one answer and then push it to the slide area. So everyone can have a look at it real quick. For the link to the blog.

Heather: Josh has put his in, too. Binaryhick.blog. If you can add that.

Matt: I have that one on there. The file path to screen time. What else do I need to add? Oh, the blog, the blog to Cellebrite’s blog. Here we go. So, would preservation request freeze that one week restriction? I don’t think it would if it’s being stored locally to the phone.

Heather: Yeah. I don’t think it would either.

Matt: If they were doing any type of cloud storage, then potentially yeah. We might be able to freeze their cloud. But yeah. Yeah, guys, I’m having to copy and paste the paths out of our side chat window. So it’s just taking just a second and I will push them out. So if you guys can give me like 30 seconds or less, maybe Heather or Paul can tell a story or something.

Heather: Well, here’s a story: tomorrow, Matt will be on Life Has No Ctrl+Alt+Delete, if you want to join. And he’s going to be talking about our new podcast. So it’ll be a fun session. And if you ever just want to kick back and relax, Fridays is just DFIR drinks, because it’s the 4th of July here in the US so it’s a holiday for us.

Paul: No cooking this week?

Heather: No, I’m relaxing.

Paul: Just drinking.

Paul: It is Canada day for us tomorrow. So we don’t have 4th of July, so a little different from us, but for those that do end up listening to the podcast, it’s actually pretty interesting, and you can just see and hear the difference of Matt’s voice. And it’s almost like a completely different person. The first time I heard it, it was like, wow, it’s pretty impressive.

There’s a question that came in from Tom. Do the extraction types matter in the Android newer phones to parse the wellbeing data? I will say, I’ll maybe let Barack chime in on this, but I’ll say that this probably data only comes out as part of a physical extraction or full file system extraction, that realistically in a logical extraction, you’re probably not going to see that, that level of detailed access to it for a file system. So I’ll bear on the side of caution to say that it is for for either physical or full file system extraction.

Matt: All right. I’m almost there guys. I apologize. Apparently it pushes the question and not the answers to the slide area. So inbox, let me push this one out, and you guys should get the links now. Yep. Okay.

So number one there is, that is the file path to… the formatting’s not great, but that firstdatacom.google.android.app, so on and so forth is the file path for wellbeing, and then starting at private VAR and all the way down to where it ends in dot SQLite is the file path to screen time.

The third line is Josh’s blog, and that’s specifically a link to the release of his Android 10 image. And then just after that is the Cellebrite blog for Apple screen time and what insights it leads to forensics. So, sorry about the formatting on that, guys. I haven’t pushed anything out that had that many lines in it before. But you should be able to make sense of it.

Heather: And if you can’t get it, if you email, ibegtodfir@cellebrite, we can respond with it as well.

Matt: Oh, and I forgot. I forgot Briggs. So I’m getting texts on the side. github.com/ Okay, great. And I’m going to push that one. So everybody screenshot or copy paste, whatever, I just pushed. I’m going to push the second one to the slide area here. There we go. And that is Briggs’ Github where you can find, among other things, aLEAPP and iLEAPP. You can also find his usage stats and some other parsers. So it’s a good little spot to go.

Heather: All right. Well, thank you everyone. We’ll see you in two weeks.