Julie O’Shea: Hi, everyone. Thanks for joining today’s webinar: Uncovering Windows Registry Data and the Latest Mac Artifacts. I’m Julie O’Shea and I’m the Product Marketing Manager here at Cellebrite Enterprise Solutions. Before we get started, there are a few things that I’d like to review.

We are recording the webinar today, so we’ll share an on-demand version after the webinar is complete. If you have any questions, please submit them in the questions window, and we will answer them in our Q&A at the end of the webinar. If we don’t get to your question, we will follow up with you after. Now, I’d like to introduce our speakers today: Monica Harris and Bob Keeney.

Monica is an experienced e-discovery professional. And over the past 15 years, she has specialized in the development, implementation, and training of proprietary software for companies such as KLDiscovery and Consilio. Before joining Cellebrite, she worked with the US Food & Drug Administration where she oversaw policy and procedure curation, enterprise solution rollout, and training for enterprise for agency litigation and freedom of information requests.

Monica is an active leader and mentor in the e-discovery community, and currently serves as the President of the Association of Certified E-Discovery Specialists’ ACEDS DC chapter, a board member of the Master’s Conference, and committee chair of the DC Master’s Conference. She has served as Assistant Director for the Women in eDiscovery DC chapter and collaborates frequently with the DC Women in eDiscovery DC bar and Women’s Bar Association of DC.

Bob has been working in cross-platform software development for over 20 years. Throughout his career, he has consulted in a wide range of industries and spent 20 years as the owner of BKeeney Software. He has spoken at dozens of cross-platform software development conferences around the world and has a regular column in a cross-platform development magazine. He is also passionate about FIRST Robotics and was a mentor for 13 years.

Thank you both for joining us today, Bob and Monica. If you both are ready, I’ll hand it over to you, Monica, so you can get started.

Monica: Thank you, Julie, and thank you everyone for joining us for today’s webinar: Uncovering Windows Registry Data and the Latest Mac Artifacts. For today’s webinar we’re going to talk about how to get the full picture for DFIR; including those Windows Registry and Mac artifacts, as well as Windows artifacts, as well.

Starting with some stats for a Digital Forensics Incident Response, or DFIR. Including security breaches, which have increased by 11% since 2018 and 67% since 2014, so as a trend over time, we can definitely see a significant increase there. The average time to identify a breach in 2019, right before the pandemic started, was 206 days. And then the average life cycle of a breach is now 314 days. That’s from breach to containment. So some helpful information there.

So let’s start by talking about Windows Registry data and how that can help investigators, because the proof is in the hives. Windows Registry data can be a cornucopia of information on the who, what, where, and when something took place on the system that can directly link a bad actor to the actions being investigated. It is the database that contains the default settings, user, and system defined settings for Windows computers.

For accounts, the Windows Registry will store user information, including the time they use the system. When you tie that into Internet browser information, nefarious activity can be quickly uncovered. If the user visited a suspicious site, for example, attempting to cover their tracks, the smoking gun could be found in the Windows Registry. If that same bad actor installed software from the nefarious site, the Windows Registry could also be a prime investigation source.

In addition to the Windows Registry, we also have Windows artifacts, including feature usage. Feature usage can give insight into a user’s behavior, such as how often they switch between applications, look at the Windows clock or start the start menu or click on the start menu, and items on the taskbar.

Feature usage is also another way of confirming software that has been run interactively by an account and how many times the software was run. By analyzing the feature usage, a DFIR professional may be able to further validate their findings with other known artifacts to help strengthen their findings during an investigation.

And last but not least: internet log parsing, the gold mind of DFIR. When conducting DFIR, browsers are a gold mind. They are often the source of incidents and malware, which can be traced down using the artifacts found inside of the browsers. From the navigation history to download files, browsers are a critical piece in any forensics analysis.

So now to take a look at the Windows Registry and Windows artifacts, Bob, I’ll turn it over to you for a demo.

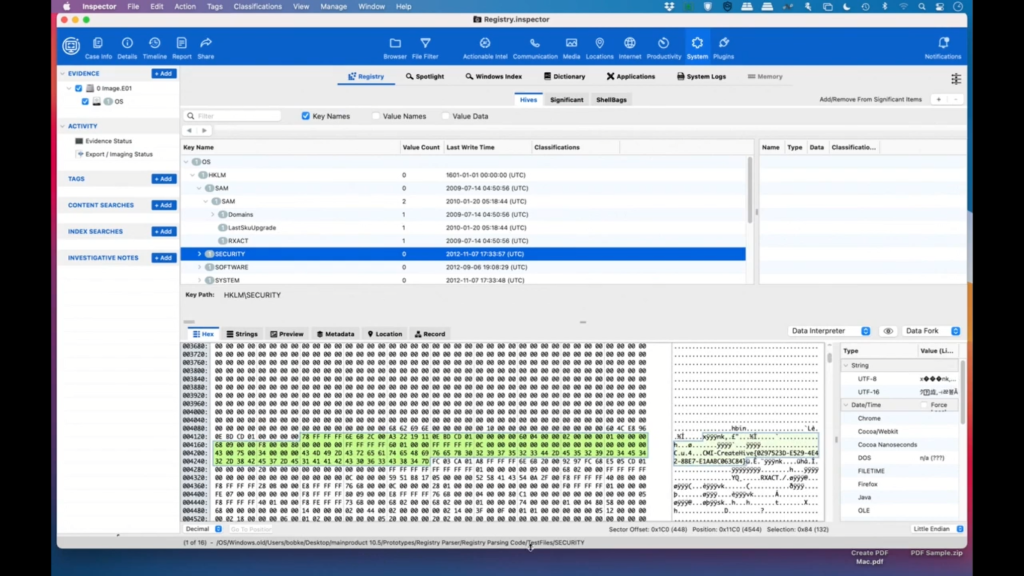

Bob: Thank you, Monica. Thank you everybody for attending the webinar today. We are going to talk about some Windows artifacts right now, and we’ll jump first into the registry.

Now, the registry has a lot of information. Almost everything you could ever think about in a computer is in there somewhere. There’s system information, there’s user information, security and so on. It’s big. There are millions of rows of data to look through. So an experienced investigator can find some interesting things by knowing what to search for.

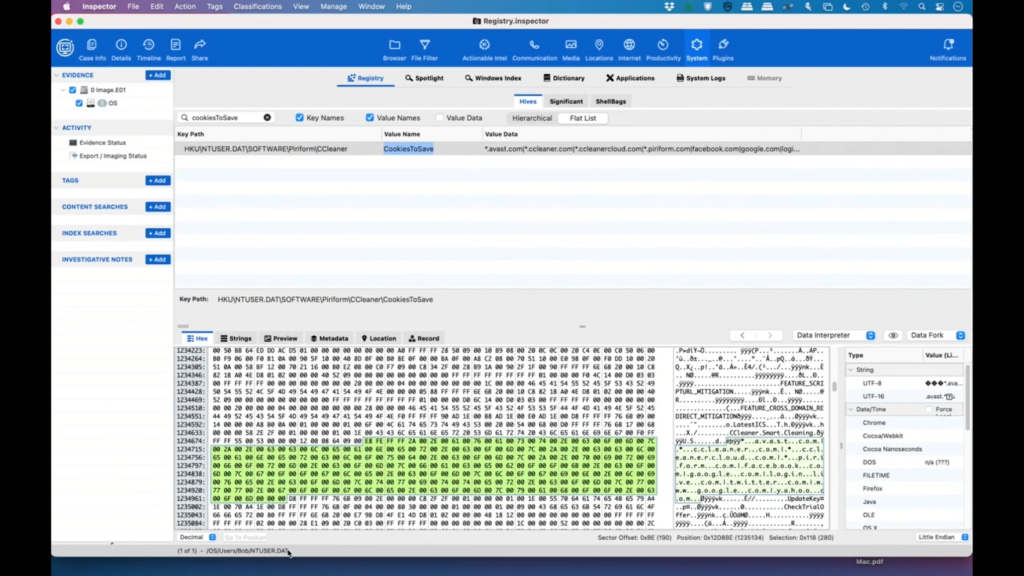

And I’m going to start off by searching for “CookiesToSave.” And the reason I’m doing this is if somebody wipes their computer history or their internet history, they may not have other things, but since this is in the registry, a lot of applications don’t actually clear this. So we’re going to try it out and see what happens.

So as you can see, we came up with a hit on CookiesToSave, and we can look at the value data here. And we see that there’s a number of websites that we have saved cookies for.

Now, a lot of websites will save cookies without the user even knowing it. So we clicked on it and we can see down here in the hex data, that’s cookies to save, and we click on the next one and we can actually see some of the raw data.

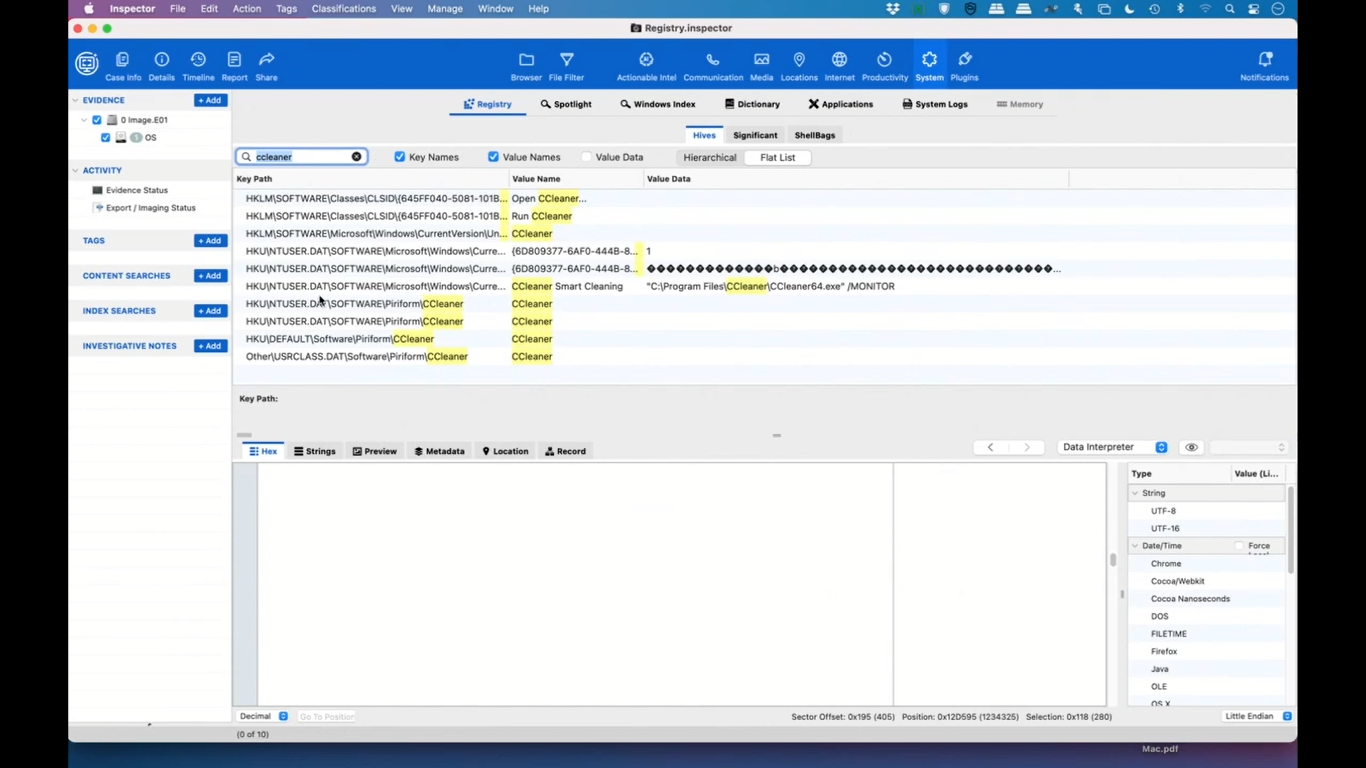

Now, this data is actually coming from ntuser.dat, which is pretty common for most computers. So we saw CCleaner here, which is an application that many people use to wipe their computer. So if we want to get something, get rid of data that you don’t necessarily want other people to see, you could run CCleaner. Sometimes it affects the registry, sometimes it just affects software, sometimes just files. So let’s take a little dive deeper.

So let’s take a little deeper dive into CCleaner to see what the registry says about it. So you can see that we’ve got some things here and we’re in the flat list, we’re going to move to the hierarchy. And we can see that under software, we’ve got an entry for CCleaner, and we can see that it was run on April 12th.

And that’s kind of interesting because that points us to some other things. And so it’s very important to be able to look at the registry and to be able to search the key names, value names, and value data for little bits and pieces of information that might be useful.

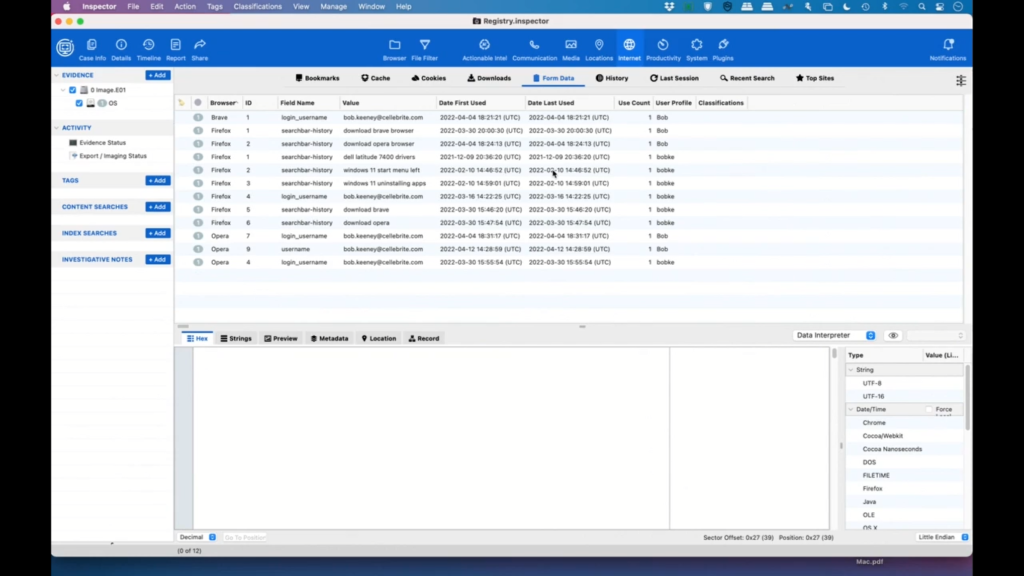

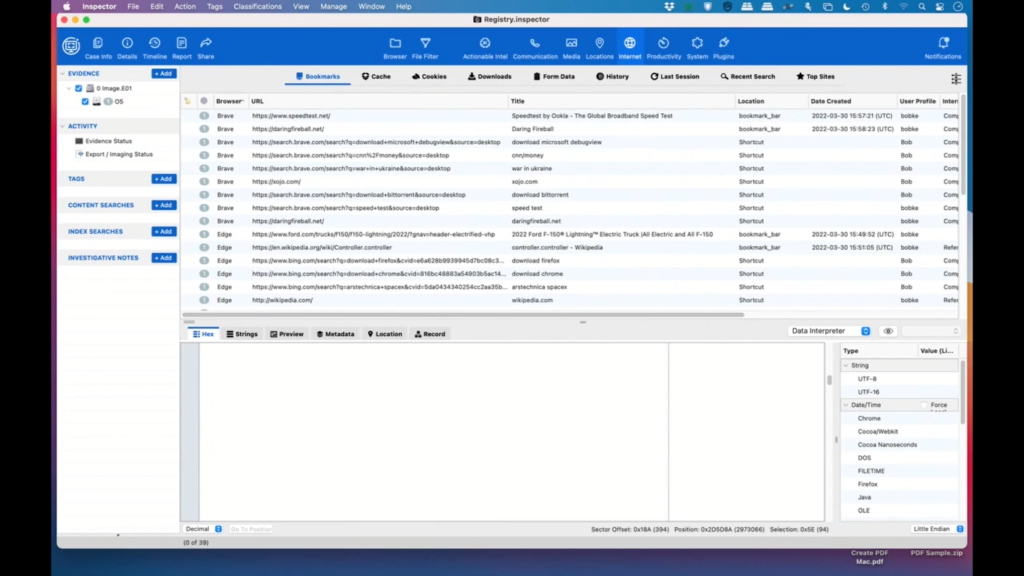

If there are no other questions I will move on to the next part, which will be the internet browser data.

Okay. So, under internet, we are going to see we’ve got all this data available; so bookmarks, cash cookies, downloads. Because we’re interested in CCleaner, let’s see what this user has downloaded.

So we can see that right here we have BitTorrent, that might be interesting; they’ve downloaded Edge, Firefox, and Chrome and Brave, which leads us to all sorts of questions of why is this user using so many different browsers?

So, and then down here, we can see that they attempted to download CCleaner twice. So once they actually did it, and once they started it, but did not finish it. And as you can see, you know, we have cookies and cache and form data, and these are all little things that can help an investigator find more information from the user’s browser. So unless they’ve specifically deleted these files and information, there might be a wealth of information here.

Okay. So with that, I think, unless there are any questions, I’m going to switch over to featured usage.

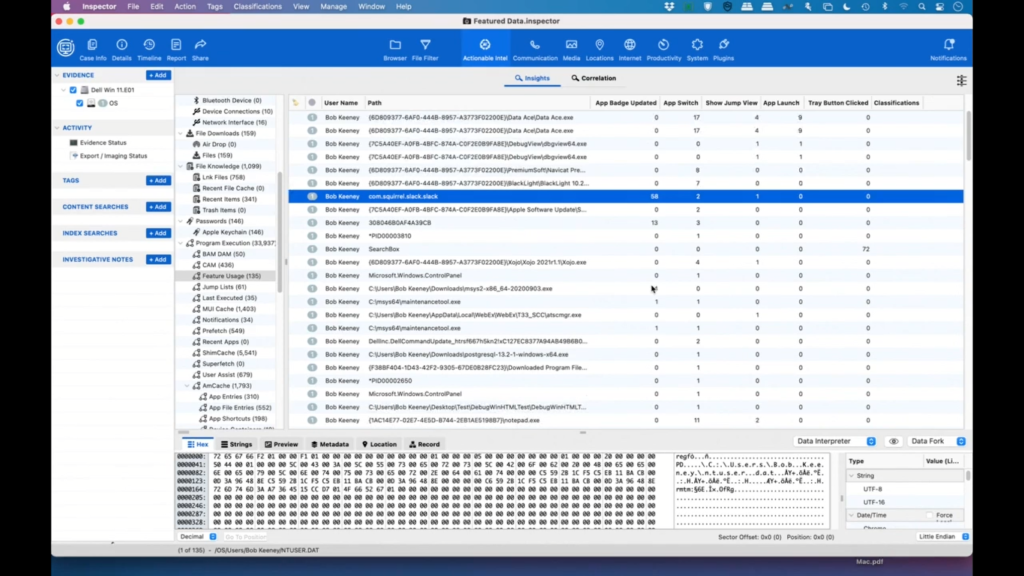

Now, featured usage is an interesting phenomenon on Windows. So, users can pin items to the taskbar in Windows, and these are the applications that you would use most often. And that way you don’t have to go to the start menu or type for it or whatever. It’s just there because it’s so easy, it’s one quick, and the Windows operating system actually keeps track of all those.

So we can see some data here. So the app badge updated that would indicate things like downloads complete, or how many unread messages somebody has, an email application, the app launch here shows how many times that the application that was pinned, the taskbar was run.

The app switch shows how many times it was just left-clicked on the taskbar. The show jump view is the number of times that the application was right-clicked on the taskbar. And then finally the trade button click would show us how many times that they’ve clicked for the clock or the start button, et cetera. So this can show us some interesting usage patterns.

So we’ll just sort this by the app launch column. And you can see that we’ve used Windows Explorer quite a few times. And because there are two entries, this may mean, well ,actually there’s probably a good explanation for this. So here’s ntuser.dat, and then here’s windows.old.

So the reason why there are two entries is this shows us that the user installed Windows and then reinstalled Windows and then kept using it. So again, this might lead us to other questions of why did somebody install Windows twice? You know, it’s not an uncommon thing to do, but it’s a good question that might lead to other answers.

So you can see Chrome was downloaded and Slack gave us a bunch of badge updates. And again, these are all just patterns that help us understand what the user is doing. So between the registry and the Internet data and the feature usage, you can kind of get a feel for what a user is doing on their Windows machine.

And with that, unless there are any particular questions for Windows, I will hand it back to Monica.

Monica: Thanks, Bob. And now let’s talk about the latest Mac artifacts starting with Apple Screen Time. Starting with Apple Screen Time and Apple Wallet.

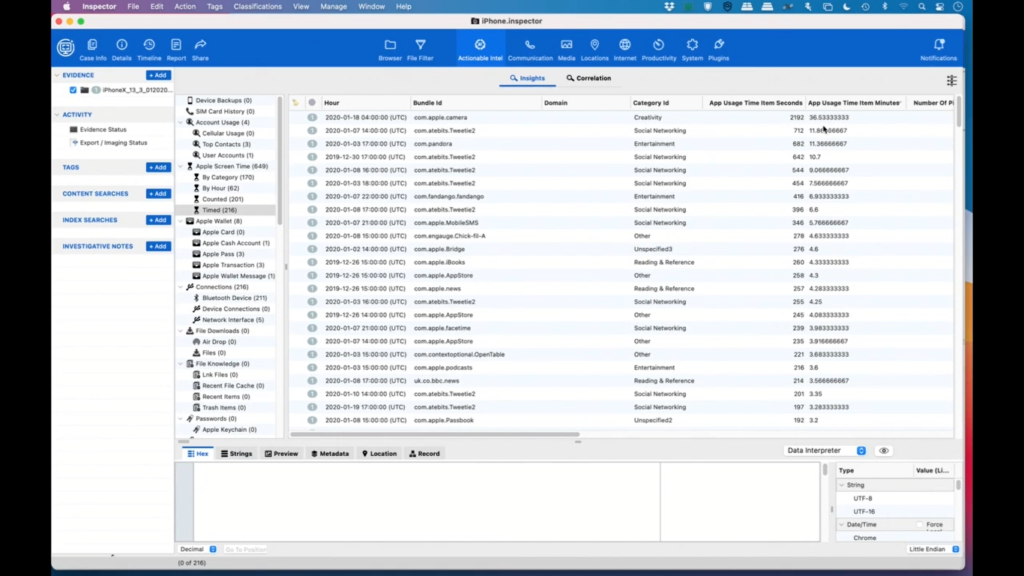

Apple introduced the Screen Time feature with the release of iOS 12 in September of 2018. The feature empowers users with insight into how they are spending time with apps and websites; creating detailed weekly and daily activity reports that show the total time spent in each app, usage across categories of apps, number of notifications received, and how often a person picks up their iPhone or iPad.

Screen Time monitors usage data. Investigators can use this data to narrow down the usage of an app to a time window that is as narrow as one hour or as wide as five hours.

For Apple Wallet, with more than 127 million users, Apple Wallet, and specifically Apple Pay, a form of cryptocurrency, is one of the most popular contactless payment systems. Apple Pay serves as a digital wallet, digitizing users’ payment cards and completely replacing traditional swipe in and sign and chip-and-pin transactions. However, unlike traditional wallets, Apple Pay also keeps detailed information about the user’s point-of-sale transactions, including location.

And last but not least; Apple Maps, the default map system of iOS. It provides directions and estimated times of arrival for walking, cycling, and public transportation navigation.

Over the years, Apple has added proactive location suggestions; integration with public transportation; 3D maps; integration with ride sharing services like Lyft and Uber; reporting accidents, hazards, and speed checks. All this information and more can help investigators track bad actors through their day-to-day activities.

And with that, Bob, I’ll turn it over to you to show the latest Mac artifacts in a demo.

Bob: Thank you, Monica. We will start looking at the Apple Screen Time. And Apple Screen Time basically shows us what the user is doing on a weekly basis. So we get this report on our iPhone and Mac about how much time we’re spending on the screen. And sometimes this is shared between devices, sometimes it’s not.

In this case, we have iPhone data. And so by category, we can sort by minutes and we can see that they spent 36 minutes doing creativity. You know, these are all categories that Apple has made. So they may or may not make a lot of sense, but we can see by how much time they’ve spent with each one. Perhaps the most interesting one is counted.

So the number of notifications is how many times the app has signaled for the user to do something, some notification. And then certainly, number of pickups from that notification, and then number of pickups without app usage.

So let’s do a sort on the number of pickups and we can see that they’ve been doing some mobile SMS. I’m not sure what Bridge is, but they’ve been listening to podcasts, and there’s a whole wealth of information here. So it’s really just a matter of looking through it and getting ideas for what’s going on.

So probably the other category that is the most interesting is the time. So let’s sort this by app usage minutes. And we can see that they’ve spent 36 minutes in the last week on their camera. So maybe they were filming something, maybe they were taking lots of pictures.

We can see that they spent a little bit of time on Tweetie too, which is a Twitter client. They spent some time in Pandora, as well. So all these things together can give an idea of what the user has been doing in the last week.

And with that, I will move on. Because this is with us all the time, Apple Wallet is becoming very popular with users and this data is not easy to get because no one wants to share their data.

So we don’t have a lot of data, but we can see that in January of 2020, this person got a Starbucks card and you can see that they’ve enabled some certain things. Depending on when this data was captured, there may actually be location data that you might be able to share here.

But perhaps the most interesting thing is transactions. So we can see that the user spent $15 on January 8th using their American Express card, and, we keep going over, we can see that they were at a Chick-fil-A. And, you know, believe it or not, they got a hot dog at Chick-fil-A, I’m not quite sure why. And then they went to Target a little bit later, and we can see that that was for $9.99.

So this is another pattern of what a user was doing. So you’ve got dates, you’ve got amounts, you’ve got the vendor, and you’ve got all sorts of things. You can also send money via Apple Pay. So again, there might be messages in here that could be useful for an investigator to try and find out more information.

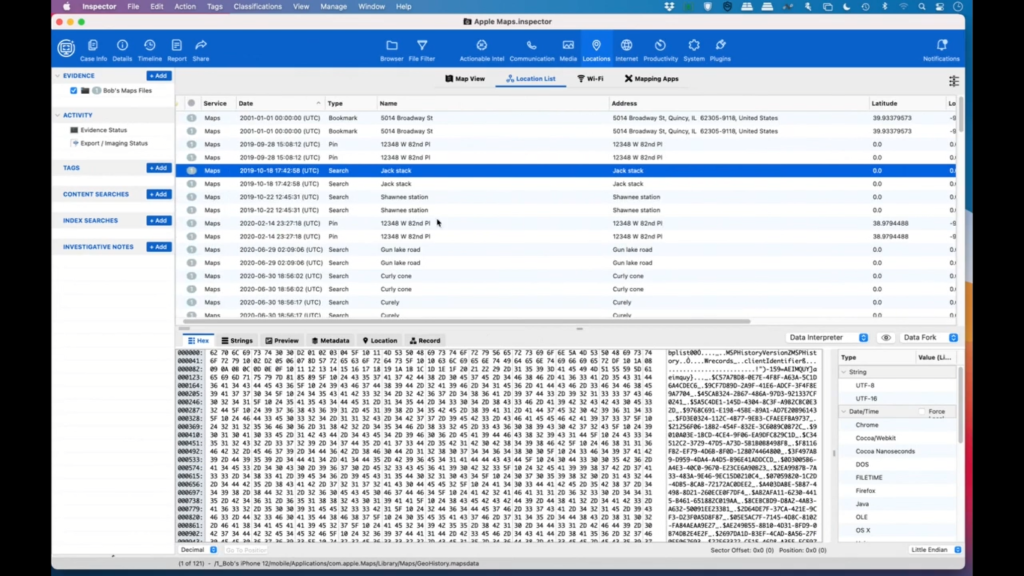

So now I’m going to switch over to Apple Maps, and Apple Maps is another one of those pieces of information that is really hard to get at because Apple really doesn’t want us to get to it. And we can see here, I’ll make this a little bigger. We’re just showing a whole bunch of different types of data.

So we can see bookmark data. So if I’m doing a bookmark in Maps, we’re seeing it; if I do a pin drop, we’re seeing it; and we’re even getting some direction endpoints. So I’m going to switch over from the Map view to the location list so that we can see a bit more data. So we’ve talked about the bookmarks, we’ve talked about the pins, we’ve done a search.

So in this case they searched for Jack Stack and they didn’t, well, they did find something, but it’s not telling us where it is, but we have directions for the end points. Unfortunately we don’t have the middle endpoints, but it’ll give us the starting endpoint and the last endpoint, pin places, direction search, and we even have failed searches.

So we don’t know why the search failed, it could be that this address doesn’t really exist, or it could be that they had lost an internet connection, which was probably more likely in this case.

And there’s just a lot of wealth of data. So you can find where this person was at, you can be reasonably accurate within, you know, 10-20 meters of where they were at, and this is all useful. Investigators love this sort of stuff. And with that, I believe that is all of the Apple artifacts we’re going to show off.

Monica: Thank you, Bob. And with that, that concludes our presentation today. And I’ll pass the mic back to Julie. Julie?

Julie: Thanks, Monica. So we have had a few questions come in. So let’s see here. Let’s start with the first one on registry data. Can you show me where this data is located on the user’s machine?

Bob: Right, I can take that one. So because we are searching the entire image for all the various registry hives, you can see that this one comes from a SAM file in, and again, this is windows.old, so we’re getting data from the previous Windows system as well as the new one. And we can see that this one will come in, again, this is the old one, but we’re just seeing data, here’s security.

Again, this is coming from the various parts of the operating system, and it’s going to vary a little bit per system, but all the users, all of the hardware and all that are going to be there. And obviously the nice thing about it is you can come in through here and search even more data and go up and down the hierarchy and find additional data.

Julie: That’s great. Thanks, Bob. Our next one. Okay, in regards to internet browsers, what are some of the reasons a user might be using multiple browsers? For example, why would someone use Brave for just a couple times instead of their usual Opera or Edge browser?

Bob: Okay, that’s a good one too. Brave has some interesting security features to it where, you know, its claim to fame is privacy, and can’t be tracked in a lot of cases. So if somebody’s using Edge or Opera or Firefox or Safari most of the time and they switch to Brave for just a little bit, that’s probably because they’re trying to hide something or maybe they’re doing sensitive information that they don’t want saved. So that would be my guess as to why they’re doing that.

Julie: That makes sense. Okay, how about, let’s see, when talking about Apple Maps, why is this data hard to get?

Bob: So there are two reasons for that. The first one is the file format. So we are decoding what’s called protobuf, which is short for protocol buffers, and it was developed by Google. And it’s kind of an extensible language format that’s a little bit like XML, but it’s smaller and faster.

And as a developer, it’s really easy to use, but to get information out of it, we sort of have to reverse engineer what the format is to extract the data out of it. And Monica can probably answer the second part in that Apple doesn’t make it easy to get the data to begin with, and I’m not quite sure which product it is that can help with that, but I’m sure Monica can help.

Monica: Thanks, Bob. That is true. Apple definitely does not make the data easy to collect to begin with. In order to collect this type of data, we recommend that you have a full file system extraction if possible. And at Cellebrite, that would be our Mobile Elite solution.

Julie: Thanks, Monica. And how about this one on screen time? How long of a time period is screen time good for?

Bob: Apple reports on Apple Screen Time every week. So as far as I know, the only data we have is based on that weekly usage and I believe Sunday morning it gets reset. So if you don’t have a lot of data, it could just be that the period has been too short or it’s just been reset.

Julie: Great. Well, thanks. That was super helpful. And I appreciate both of your time today. It looks like we’re coming up on the end of the webinar, the 30 minute mark here. So any questions that were submitted, we will follow up with you after, we will reach out individually, so keep them coming if you have any more.

And if anyone wants to learn how to get started with any of our solutions, check out the contact desk button you’ll see at the bottom of your console. And of course after the webinar today, if you get a second, if you could please fill out our feedback form on what you’d like to see going forward, that will help us decide our future webinar.

So thank you again, Bob and Monica, that was super insightful and very helpful I’m sure for our attendees today, and thank you for joining, everyone. Hope everyone has a great rest of their day.