What is the most urgent question facing digital forensics today? That in itself is not a question with a straightforward answer. At conferences and in research papers, academics and forensic practitioners around the world converge to anticipate the future of the discipline and work out how to overcome some of the more challenging aspects of the field.

In September 2015, Forensic Focus ran a survey of digital forensic practitioners. Almost five hundred people responded, giving their opinions on a wide range of subjects from current challenges to child protection.

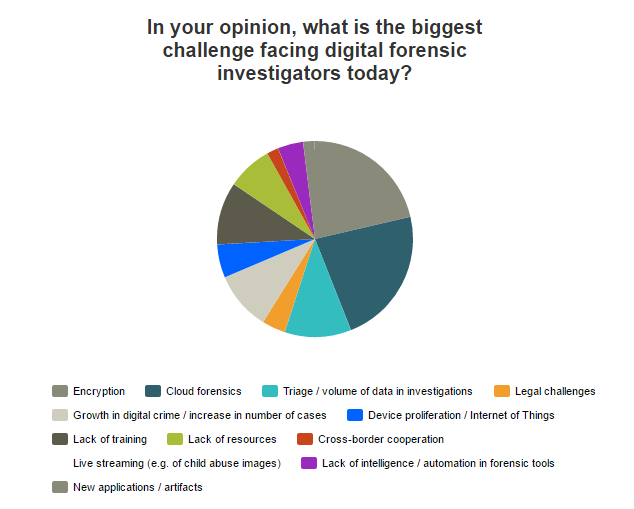

The question ‘In your opinion, what is the biggest challenge facing digital forensic investigators today?’ prompted a plethora of answers. Researchers from University College Dublin’s School of Computer Science have also been grappling with this question recently, as evidenced by a recent paper from David Lillis, Brett A. Becker, Tadhg O’Sullivan and Mark Scanlon.

The results of the Forensic Focus survey indicated that cloud forensics and encryption were two of the things investigators are most concerned about. Triage, or the increasing volume of data per investigation, was also a concerning factor, as were the growth in the number of digital crimes and a lack of training and resources in the field.

Regarding the difficulty of investigating cases where multiple devices may contain evidence, Lillis et al point out that “mobile and IoT devices make use of a variety of operating systems, file formats and communication standards, all of which add to the complexity of digital investigations. In addition, embedded storage may not be easily removable from devices, unlike for traditional desktop and server computers, and in some cases a device will lack persistent storage entirely, necessitating expensive RAM forensics. Investigating multiple devices also contributes to the consistency and correlation problem, where evidence gathered from distinct sources must be correlated for temporal and logical consistency. This is often performed manually: a significant drain on investigators’ resources.”

In a field in which a lack of training and resources has also been posited as a major challenge, the concern that overworked investigators are performing manual examinations of multiple devices becomes paramount. We are all familiar with the concept of “push-button” forensics, in which investigators are given basic training in the use of a certain tool without a thorough understanding of its inner workings and methodology.

Interestingly however, the thing that concerned Forensic Focus’ survey respondents the most was neither triage (11%) nor device proliferation (5%), but cloud forensics (23%) and encryption (21%).

The UCD research paper agrees that cloud-based data storage is a challenge.

“Typically, data in the cloud is distributed over a number of distinct nodes unlike more traditional forensic scenarios where data is stored on a single machine. Due to the distributed nature of cloud services, data can potentially reside in multiple legal jurisdictions, leading to investigators relying on local laws and regulations regarding the collection of evidence. This can potentially increase the time, cost and difficulty associated with a forensic investigation. From a technical standpoint, the fact that a single file can be split into a number of data blocks that are then stored on different remote nodes adds another layer of complexity thereby making traditional digital forensic tools redundant.”

In a presentation at TDFCON in 2015, Janice Rafraf, a law student at Teesside University, spoke about some of the main challenges concerning cloud forensic investigations. Not only are there the more obvious difficulties such as understanding how to access data stored in these relatively new environments, there are also legal concerns. Cloud-based investigations tend to be international, with data being stored in several physical locations, some of which may not be legally accessible, without even beginning to discuss the technical difficulties.

Cloud services are widely used for legitimate means as well, of course; but the rise in anonymising tools and distributed data storage makes it easier than ever for criminals to cover their tracks.

Scanlon et al elaborate in their paper:

“The use of IP anonymity and the easy-to-use features of many cloud systems, such as requiring minimal information when signing up for a service, can lead to situations where identifying a criminal is near impossible [Chen et al., 2012, Ruan et al., 2013].”

Speaking of anonymity and covering one’s tracks, the question of encryption is a thorny one in the field of digital forensics at present. With the recent legal battle between Apple and the FBI, and the subsequent decryption of the iPhone in question by an unknown third party, encryption has been at the forefront of the headlines and of people’s minds, bringing it into the public sphere more than ever.

We asked Yuri Gubanov, CEO of Belkasoft, about the forensic challenges of encrypted devices and how much of an impact they have on investigations.

“There is no single answer to this question. The challenges (and acquisition approaches) vary greatly between devices. For example, full-disk encryption on Windows desktop computers (BitLocker) can be attacked by capturing a memory dump via a kernel-mode tool (such as Belkasoft Live RAM Capturer) while the volume is mounted, and analyzing that memory dump to extract the binary decryption key. This allows mounting BitLocker volumes in a matter of minutes.

When talking about Android devices, the answer is “it depends” on who made the device and what version of Android it’s running. In many cases, Android devices can be dumped and decrypted even if the passcode is not known (this no longer works on Android 5 and newer, and does not work on Samsung-made smartphones since Android 4.2).

When talking about Apple smartphones and tablets, their implementation is exemplary, especially since Apple started using Secure Enclave in 64-bit hardware (iPhone 5S and newer). For such devices, other acquisition paths are used such as cloud acquisition.

Finally, if only some data is encrypted (e.g. by using NTFS encryption), the real challenge is in actually locating the encrypted data. This is not an easy task as one might think. The encrypted file detection module for Belkasoft Evidence Center has a proprietary method implemented in order to be able to tell apart compressed files (e.g. ZIP, JPEG) and encrypted data.”

So what can be done in investigations where encrypted devices are essential for evidence? How can forensic practitioners rise to the challenge?

According to Gubanov, workarounds and exploits are the way forward.

“Most encryption schemes are designed to withstand brute-force attacks, so directly enumerating encryption keys and/or passwords is rarely possible (unless the same or very similar password was re-used on multiple accounts). In order to overcome encryption, experts are using a number of workarounds.

For example, a BitLocker volume can be unlocked if one knows the correct Microsoft Account password (if that is the case, one can simply retrieve the corresponding escrow key directly from Microsoft Account). Recovering that password is another story, but there are tools and techniques for doing that. One more method would be capturing a memory dump with Belkasoft Live RAM Capturer or a similar tool, then extracting a binary decryption key from that dump.

For Android smartphones, one has to know the weaknesses of each major Android release in order to overcome the protection. Even if this is not possible, one can still extract massive amounts of information from the user’s Google account, which may contain even more data than the phone itself. Apple smartphones are configured to back up information into the cloud by default, so those backups (if available) can be obtained and analyzed instead of attempting to break the device.”

Acquiring all the evidence isn’t the final challenge of the process, either. Even once all necessary data have been extracted, there still remains the need to go through it, work out what is useful or sufficient for the purposes of the investigation, and create a report to be presented in court or back to the client.

The research team at UCD agree:

“The digital evidence backlog is currently in the order of years for many law enforcement agencies worldwide. The predicted ballooning of case volume in the near future will serve to further compound the backlog problem – particularly as the volume of evidence from cloud-based and Internet-of-Things sources continue to increase.”

In summary, therefore, digital forensics as a field is experiencing a wide range of challenges, none of which are straightforward to overcome. In a world that rapidly develops new technologies, forensic practitioners can often find themselves desperately scrabbling to keep up. Arguably the best way of doing so is to ensure continued cross-collaboration between law enforcement agencies, academic institutions and corporate entities wherever possible. With an increasingly globalised society storing the bulk of its data online, the digital forensic field has the opportunity to use this trend to its advantage and collaborate more efficiently than ever before to help create effective solutions.

Read the full UCD research paper here. Find out more about Belkasoft Live RAM Capturer and Evidence Center here.