by Arman Gungor

Last week, I came across an interesting post on Forensic Focus. The poster, jahearne, was asking about how one can detect manipulation of an existing email in Gmail. In his hypothetical scenario, the bad actor was using Outlook to edit the message and change its contents after it was received. I wanted to reproduce this setup and examine the results to see what we find out.

The Setup

I started by performing a baseline acquisition of the target email account over IMAP—which is the same protocol Outlook would use to connect to Gmail. This allowed me to capture the Internal Date Message Attribute as well as the Unique Identifier (UID) Message Attribute for each message before any manipulation took place. I used our Forensic Email Collector to do this, but you can also capture these values by directly interfacing with Gmail’s IMAP server.

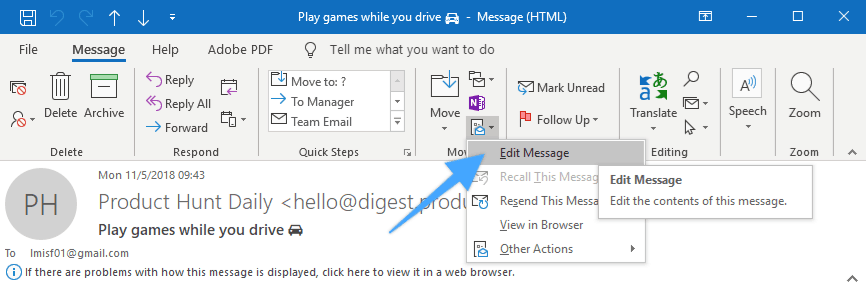

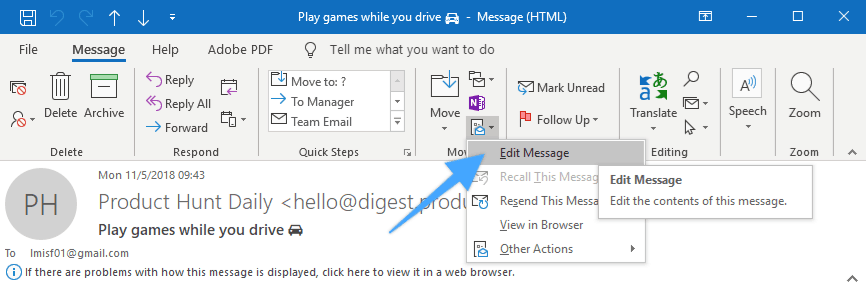

I then connected the Gmail account to Outlook 2016. Once Outlook finished downloading the messages, I picked the message that I wanted to manipulate. The original message looked as follows:

I then clicked the “Edit Message” menu item from the “Move” section in the toolbar ribbon for the email.

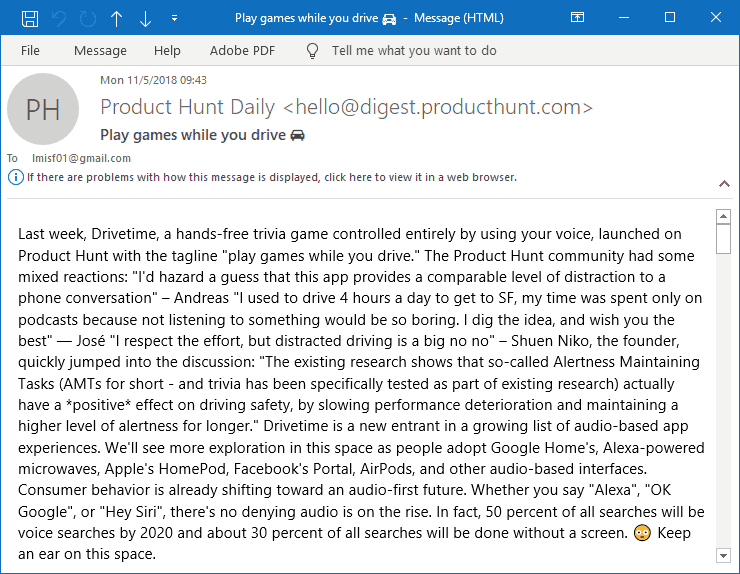

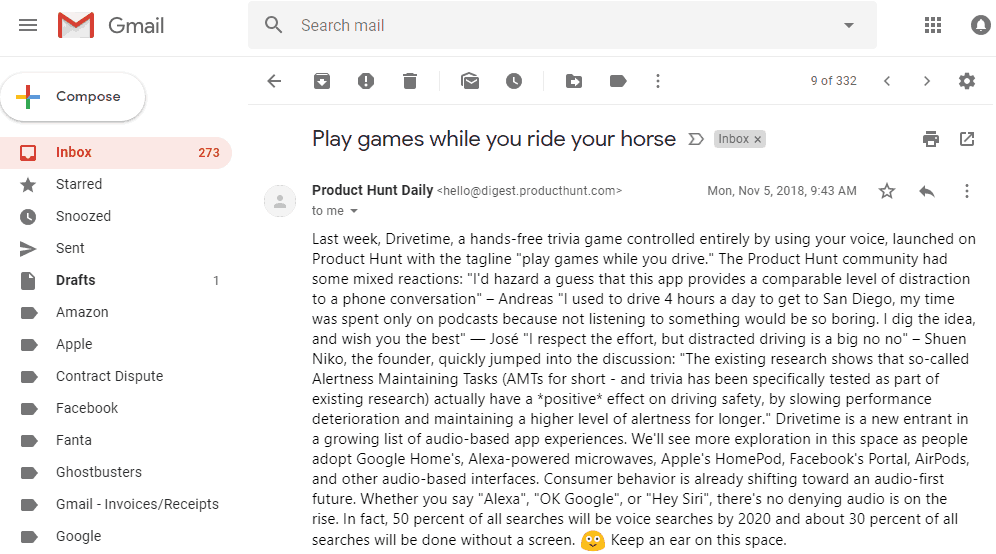

I changed the subject of the message from “Play games while you drive ?” to “Play games while you ride your horse” and changed the string “I used to drive 4 hours a day to get to SF” to “I used to drive 4 hours a day to get to San Diego” in the message body.

I clicked the “Save” button on the top left corner. Outlook indicated that it was synchronizing the folder, and voilà! The manipulated message was pushed to the server.

I double checked this by logging into Gmail’s web interface and pulling up the manipulated message. It looked as follows:

Now that our manipulated message had made its way back to Gmail, it was a good time to acquire the mailbox one more time for comparative analysis.

Forensic Examination of Manipulated Email

Server Metadata

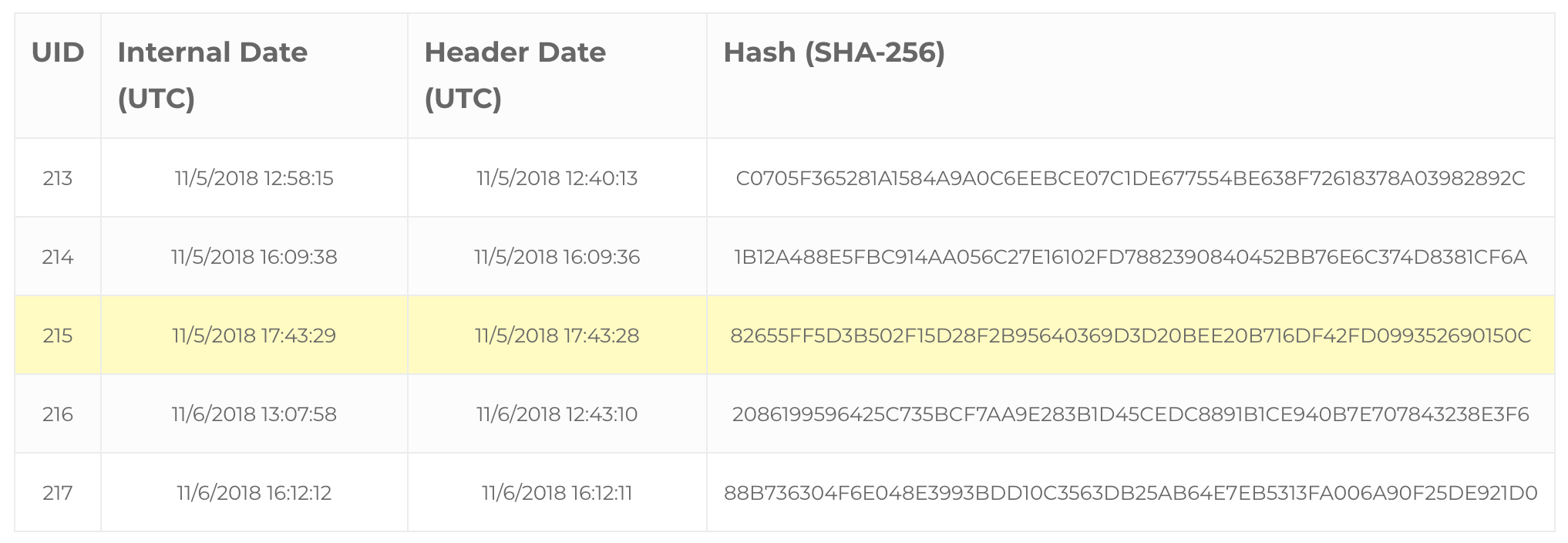

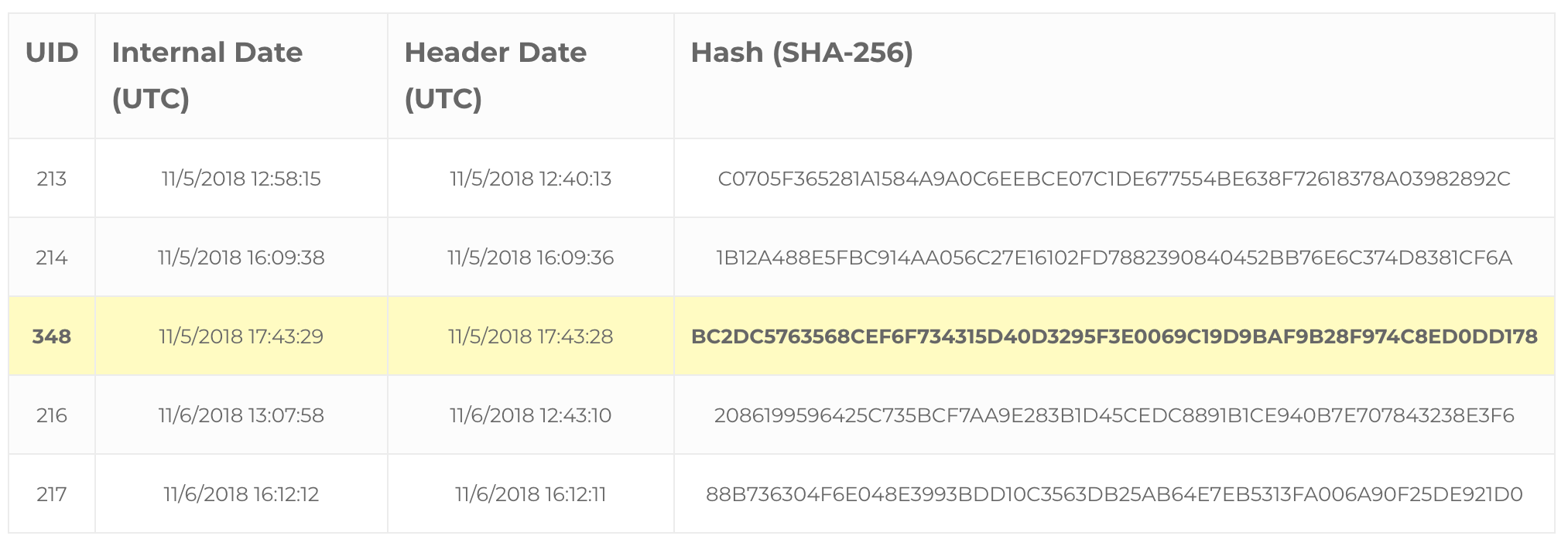

The first question in my mind was how this affected server-side metadata—the Internal Date and Unique Identifier message attributes. Before manipulation, our message (highlighted) and its four immediate neighbors had looked as follows:

Note that the UIDs were in ascending order while the messages were sorted chronologically by Internal Date.

Now, let’s take a look at the same set of messages after the manipulation:

As expected, the manipulation changed the cryptographic hash of the email message. But more importantly, it caused Gmail’s IMAP server to assign the message a new UID. Now, when we look at the messages in chronological order, the UID of the manipulated email is no longer in order. In fact, it received the greatest UID in the folder. Let’s take a look at the mechanism that caused this.

How Did Outlook Replace The Message on The Server?

In the background, Outlook issued an APPEND IMAP command to Gmail’s IMAP server and introduced the altered email into the mailbox as a new message. As an argument to the APPEND command, Outlook passed the Internal Date of the original message. The IMAP specification for the APPEND command states that:

If a date-time is specified, the internal date SHOULD be set in

the resulting message; otherwise, the internal date of the

resulting message is set to the current date and time by default.

In this case, because a date-time was specified, the Internal Date message attribute was preserved. Depending on the IMAP server and the email client that was used, you may find that the Internal Date message attribute sometimes reflects the time when the altered message was synced back to the mailbox.

After the APPEND command, Outlook set the “\Deleted” IMAP flag on the original message. Finally, Outlook issued a UID EXPUNGE command to permanently remove the original message from the mailbox.

Message Data and Metadata

Unlike scenarios where the suspect edits an existing message with a text editor and uploads it to the IMAP server, here I used Outlook to alter the message. Let’s take a look at how the manipulated email message in Gmail looks different than the original.

Message Size and Body

Editing the message using Outlook and saving it caused it to almost double in size. The total size of the message increased from 66.9 KB to 121 KB. This was mostly because of the formatting information Outlook inserted into the document.

The “ProgId”, “Generator”, and “Originator” meta tags were populated with the values “Word.Document”, “Microsoft Word 15”, and again “Microsoft Word 15” respectively—not unlike a Word document saved in HTML format.

Upon looking at the part where I had edited the message body, I found that Outlook managed to update both the HTML and the plain text versions of the message body consistently.

MIME Boundary Delimiters

The MIME boundary delimiter of the original message was “=-FqYpb1xnVuagRE/vpmLO”. After the edits, it was changed to “—-=_NextPart_000_0000_01D4B364.5C460060“.

Note that the last part of the new MIME boundary delimiter, 01D4B364.5C460060 (6000465C64B3D401 in reverse byte order), is a FILETIME value. Decoding the FILETIME value results in 01/23/2019 21:41:12.6780000. This is not the time when the original message was edited and saved in Outlook, but the time when the edited message was synced back to Gmail by Outlook. The timestamp has millisecond precision, and no time zone offset (thanks, Charles Platt, for spotting this!).

Header Fields

When the message was edited using Outlook, the header information shrank from 4,950 bytes to 2,184 bytes. This was mostly because Outlook stripped out several lengthy header fields such as “DKIM-Signature” and “Authentication-Results”.

The Message-Id header field was preserved.

One significant change was to the Origination Date (i.e., “Date” field in the header). The “Date” field of the original message read:

Date: Mon, 5 Nov 2018 17:43:28 +0000

After the edits in Outlook, the “Date” field of the modified email became:

Date: Mon, 5 Nov 2018 09:43:28 -0800

While both timestamps refer to the same point in time, the manipulation in Outlook caused the “Date” field to reflect the time zone where the edits were made!

The “Subject” header field also changed as expected. It was originally UTF-8 encoded to accommodate the “oncoming automobile” emoji (\xF0\x9F\x9A\x98):

Subject: =?UTF-8?Q?Play_games_while_you_drive_=F0=9F=9A=98?=

After my edits, the new Subject header field became:

Subject: Play games while you ride your horse

Outlook also added a few new header fields such as:

X-Mailer: Microsoft Outlook 16.0

X-OlkEid: 00000000E99D742F177E4948AB97502B6BAC12160700C3B68E10F77511CEB4CD00AA00BBB6E600000000000C

0000D9539C2261A6BB45B9DAB62C7081B3C10100E800000000006A8B4A45F8869849BA81A810114C7889

Thread-Index: AQGfn39hkC1I90ybIjXNvTnfAiwDDg==

Note that Outlook 16.0 matches the version of Outlook (2016) I used to edit the message.

Conclusions

This exercise shows just how easy Outlook makes it for an end user to edit an email message that’s on the server.

In this case, examining the server metadata along with the message itself made it clear that the message was manipulated. The manipulated email had, among other things:

- An out-of-order UID

- Artifacts in the message header and body that were inconsistent with other messages from the same sender

- A time zone offset in its Origination Date that was inconsistent with those of other messages from the same sender, and that matched the time zone where the message was manipulated

- Its X-Mailer header field populated with the name and version of the email client that was used to alter the message

- A new MIME boundary delimiter which contains a timestamp reflecting the time the altered message was reintroduced to Gmail

When forensically authenticating emails, it is important that forensic examiners capture not only the message of interest but also its neighbors and server metadata. Examining the suspect message in isolation prevents the examiner from analyzing valuable contextual evidence that lives on the server.

References:

RFC 5322: Internet Message Format

RFC-3501: Internet Message Access Protocol

RFC-2045: Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME)

Forensic Focus Post

About The Author

Arman Gungor, CCE, is a digital forensics and eDiscovery expert and the founder of Metaspike. He has over 21 years’ computer and technology experience and has been appointed by courts as a neutral computer forensics expert as well as a neutral eDiscovery consultant.